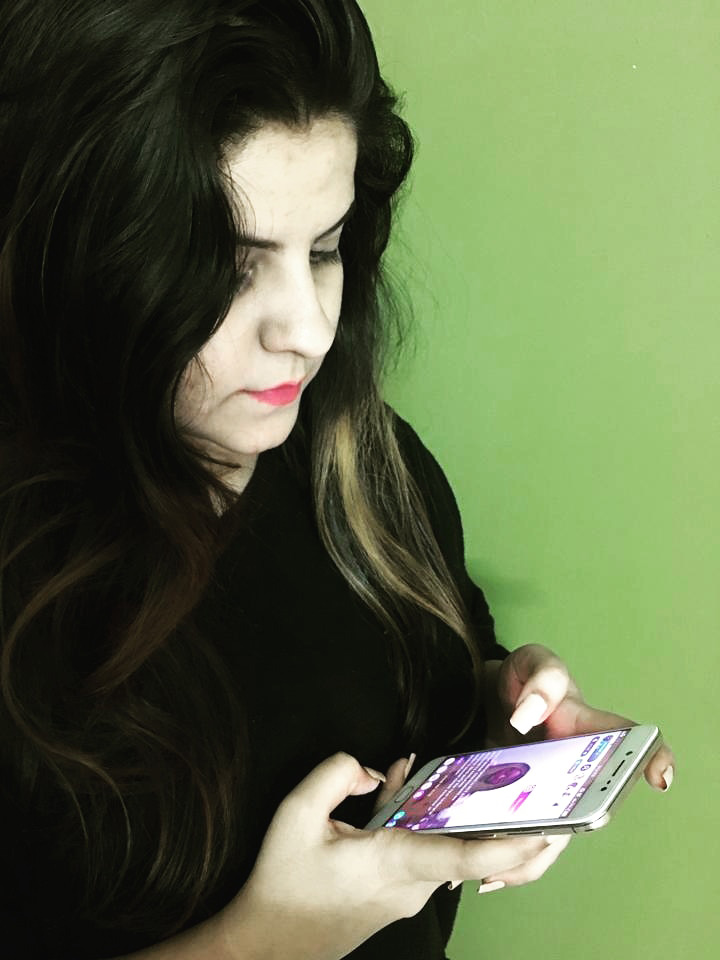

A week before the festival of Holi, Richa Kukreja is decked up in a white lehenga, hair tied up fashionably in a bun, and wearing long jhumkas, an ornate bindi on her forehead, and lip colour that matches the shades of the coral pink embroidery on her blouse. She holds a plate full of dry colours, stands in front of her tripod-smartphone camera setup, and lip syncs to a popular Bollywood song. It takes her a couple of takes to record that video. “The expressions have to be on point,” says Kukreja, a 26-year-old student of digital marketing.

It’s now time to make minor changes in her setup for the next video. With the help of her mother, she pulls down the black curtain that served as the background to reveal white drapes behind. She then replaces the content of the plate with water balloons and ties a white dupatta on her forehead. This time, she lip syncs to another popular Bollywood song on Holi.

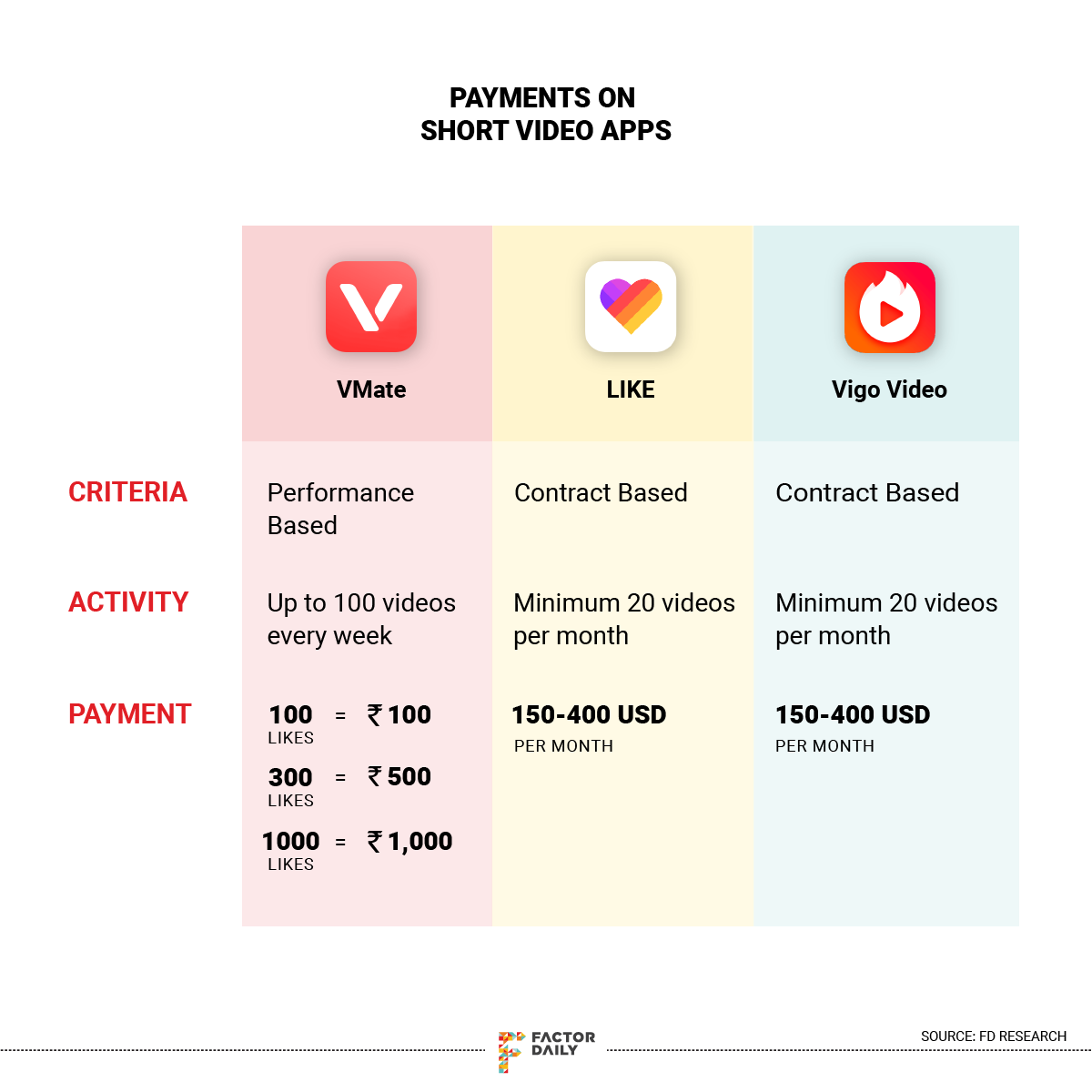

This goes on for a while — a different background, a new prop, another song. “These videos can’t be the same,” she says, explaining the need to make minor changes for every new video. Kukreja has some 138,000 followers across social video platforms VMate, Vigo Video and LIKE. Someone with that kind of following typically earns upward of Rs 50,000 a month.

Kukreja is ‘talent’ in India’s new content platform parlance. Thousands of youngsters like her are routinely wooed by apps such as China’s TikTok, VMate and Vigo Video that have received unprecedented popularity in India. After initially coming in for disdain and mockery by an elitist Instagram-preferring audience, these platforms have gained acceptance and recognition by a larger populace of mostly so-called neomobiles, or first-time mobile users. The largest of these, TikTok, recorded 52 million monthly active users in India in January, cutting close behind Instagram that reportedly has about 75 million monthly active users in the country.

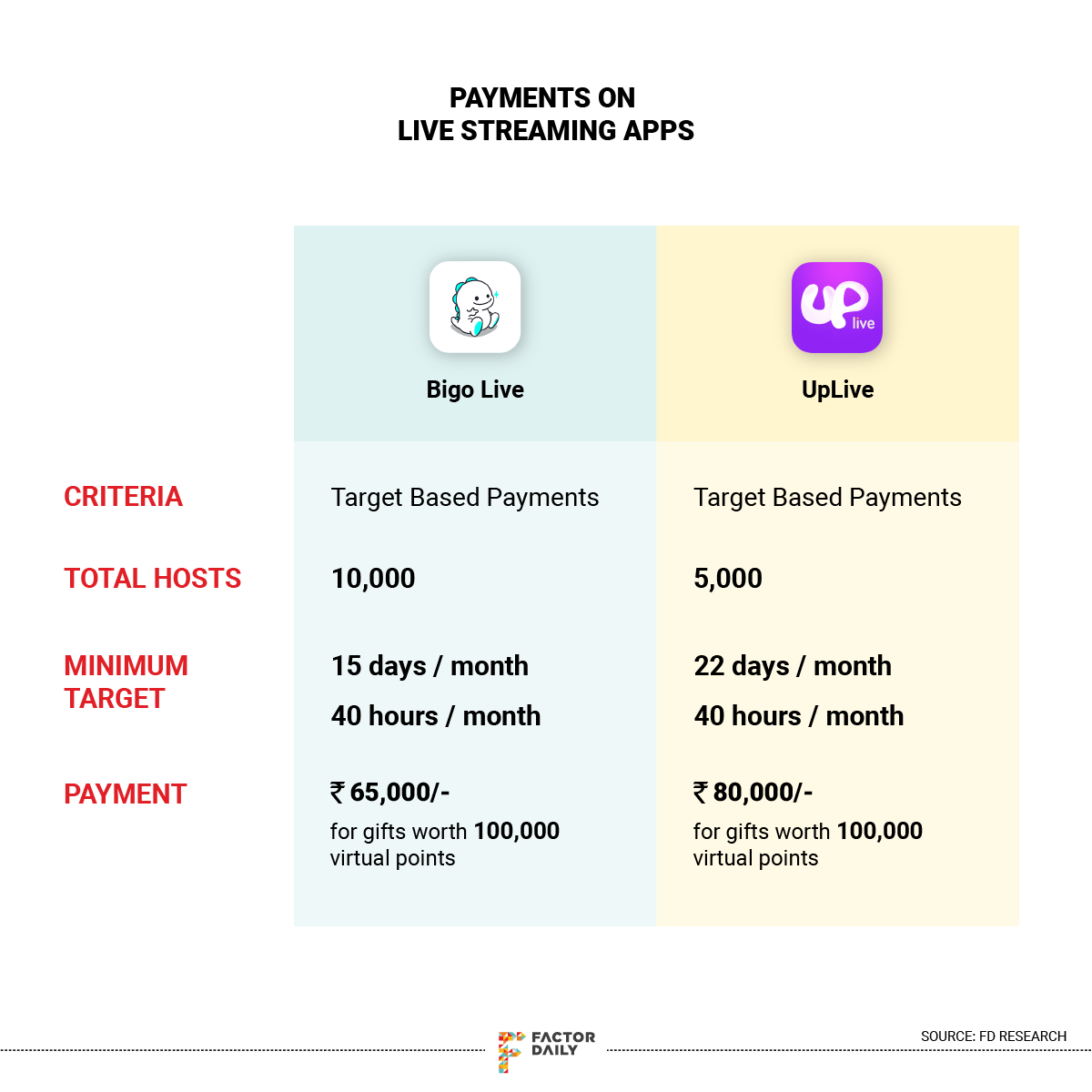

The growing popularity of these user-generated content (UGC) platforms has unleashed a scramble for talent or creators to keep their engines running. In the process, short-video and live streaming platforms have created a mini-industry of sorts fuelled by handsome payouts to twenty-somethings with passable talent. Bigo Live alone has 10,000 creators in India. For folks like Kukreja, there couldn’t have been a better time to be on the internet.

Akshay Kakkar, a 23-year-old science tutor by day, has about 300,000 fans on TikTok. Popular for his dancing skills on the platform, Kakkar says he receives multiple requests from other platforms to join them. He was recently approached by Heena Soni, a recruiter for Singapore-based live streaming platform Bigo Live. Soni promised him a decent income upwards of Rs 50,000 for live streaming himself for about two hours a day. Kakkar says he turned down the offer because he considers dancing before a live audience who throw money (virtual gifts) at him to show their appreciation to be derogatory.

While Kakkar has his reservations, Bigo Live is flocked with performers dancing, singing, mimicking and even roasting on their live broadcast streams. Soni, 21, an arts graduate who worked as an administrative executive at a real-estate company earlier, live-streamed on the platform for over a year before becoming a recruiter. Now, she is constantly browsing hundreds of profiles across social media platforms scouting for candidates who could potentially hold an audience’s attention for a couple of hours.

Among Soni’s recent recruits are a man who can complete a pencil sketch in under five minutes and a pair of twin sisters. “When recruiting men, it’s good to look for someone with some kind of skill like singing or performing. For women, even lip syncing can be an easy and effective skill,” says Soni.

Her job as a recruiter includes hunting candidates who can be turned into hosts. A host is someone who commits to spending designated hours live streaming on the platform in exchange for a monthly salary, Soni explains. Soni, who manages a team of about 70 hosts for Bigo Live, gets a cut of their earnings. She also grooms the creators on ways to get more viewers to send them virtual gifts. For example, addressing viewers by their names or taking requests for singing a song makes people feel special and, hence, obliged to return the favour.

Soni says that about six months ago the challenge for a recruiter was to address a potential candidate’s apprehension and reservations about live streaming or performing on camera for a bunch of strangers. While the reservations haven’t eased entirely, there are too many recruiters trying to get the same candidates on board. “If you see a new broadcaster live streaming, there are at least 10 recruiters (trying) to convert them into a host,” says Soni.

For all the buzz, payouts to creators have reduced over the past year. Until July last year, VMate, a short-video app by Chinese internet giant Alibaba, paid popular creators Rs 300 per video. But in August, the platform introduced rules to pay creators based on the number of ‘likes’ received per video. Kwai, a short-video app by Tencent-backed Kuaishou, used to pay its creators Rs 500 per video but has stopped payments and withdrawn its marketing operations from India with TikTok dominating the domestic market.

Kwai represents perhaps an early signal that all may not be well in India’s short video and live streaming industry.

Several social video apps targeting new internet users in India, specifically those from small cities and towns, have gained significant popularity over the past year. Many of these, including short video platforms TikTok, Kwai, VMate and live streaming ones like LiveMe and UpLive, have origins in China. Live streaming, now a $5 billion industry in China that’s backed by talent and agencies, has evolved from girls live streaming for an hour to make a quick buck to a full-fledged 9-9-6 (9 am to 9 pm, six days a week) job.

That kind of growth is yet to happen in India.

What the Chinese companies in India have been able to do is paint the town red with their customer and creator acquisition numbers, says Prateek Lal, founder of Mumbai-based digital content company Talent Dekho. But they haven’t been able to increase engagement even with all this talent, he says.

“Talent shows that have been running on Indian TV successfully for 15 years are still popular because they offer a hope that in the end if you win the gratification is very high,” Lal says. No amount of digital badges, crowns or points through apps can deliver such gratification, he says.

Lal expects that in the next six months or so at least a few Chinese platforms would back out of India realising they wouldn’t be able to sustain over the long run.

The influencer (internet celebrities) space in China is way ahead and more evolved as compared to that of India. With over 802 million active internet users, China’s Wanghongs (internet celebs) earn more than A-list movie stars in the country. A highly integrated digital ecosystem operated by local giants Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent that control the entire digital chain, from search to video streaming to social media to payments and digital commerce, enables effective and seamless monetisation of these products.

In fact, influencers or key opinion leaders (KOL) are so imperative for digital commerce in China that platforms like WeChat (a super app where users can chat, shop and pay) have evolved their products to favour KOLs. Live streaming platforms powered by e-commerce players like Taobao allow streamers to broadcast brands and products to their viewers, who could watch and seamlessly purchase those products on the same platform.

In India, live streaming is a two-year-old phenomenon. Short-video platforms have been a rage for about a year. Bigo Live, which launched officially in India in May 2017, was one of the earliest entrants in the space. Two years down, the platform is filled with videos of women showing cleavage and some women in battle with another as viewers decide who is prettier (by rewarding them with virtual gifts.) Of course, the viewers are generally men. There are also many men who host broadcasts.

One popular streamer, Azfar Aas, aka Sameer, who was rewarded the ‘best male host’ title at Bigo’s annual awards, earns about Rs 1 lakh a month through the platform. Aas broadcasts daily from 11 pm to 1 am, a time slot that works for his 2.1 million fans, many of whom, he says, are based in the Middle East.

His broadcasts are generally a virtual representation of what happens when young men catch up after day’s work at a neighbourhood ‘nukkad’, or a nook.

The 22-year-old Gurugram resident concedes he doesn’t possess any special talent but says he knows how to make people feel like they are talking with their closest friend. Aas, who has an engineering diploma but discontinued his job as a quality inspector at a manufacturing company, has bought two cars from the money earned through Bigo Live. He has leased the cars to ride-hailing companies, which fetches him an additional income of about Rs 50,000 a month.

What does a 22-year-old do with all that money?

Aas says he has an appearance to maintain. He can’t wear clothes that are not branded. His fans, mostly men, want to know what watch brand he is wearing, where did he get that blazer from. Aas says he live streams from a men’s parlour because his fans want to view his haircut. He often travels across the country, stays at expensive hotels, and live streams from new locations.

If and when live streaming platforms in India mature to the level of those in China, the likes of Aas could potentially help build an influencer network that could get brands on board. Currently, live streaming platforms in India generate about $500,000 a month in revenue, according to a top executive at a live streaming company that operates in India, who declined to be identified.

“Platforms like Instagram that have a huge influencer network are missing out on more than $1-billion in revenue that they can generate by getting a cut out of the influencer revenue,” the executive adds. The live streaming networks are making use of that space.

Jovan Martins, business head at Kwan Entertainment, a talent management company that works with TikTok and LIKE, among others, in India, says though the creator ecosystem for the new platforms doesn’t appear streamlined, in the future influencers are likely to emerge from these platforms. Just the way YouTube eventually found a way to celebrate and recognise good talent.

“The digital industry, by nature, is very dynamic. The influencer network that was once dominated by Facebook later moved to Instagram, with TikTok now following closely behind,” says Martin. YouTube still remains at the forefront of building out influencers.

For now, the primary source of revenue for live streaming platforms in India is virtual gifting, which has users purchasing digital currency or tokens using real money to send to their favourite creators. A gamified experience encourages users of live streaming apps to send virtual gifts. A time-bound face-off between two popular creators is one of the easiest ways to make people send more gifts. Contests and challenges also work well.

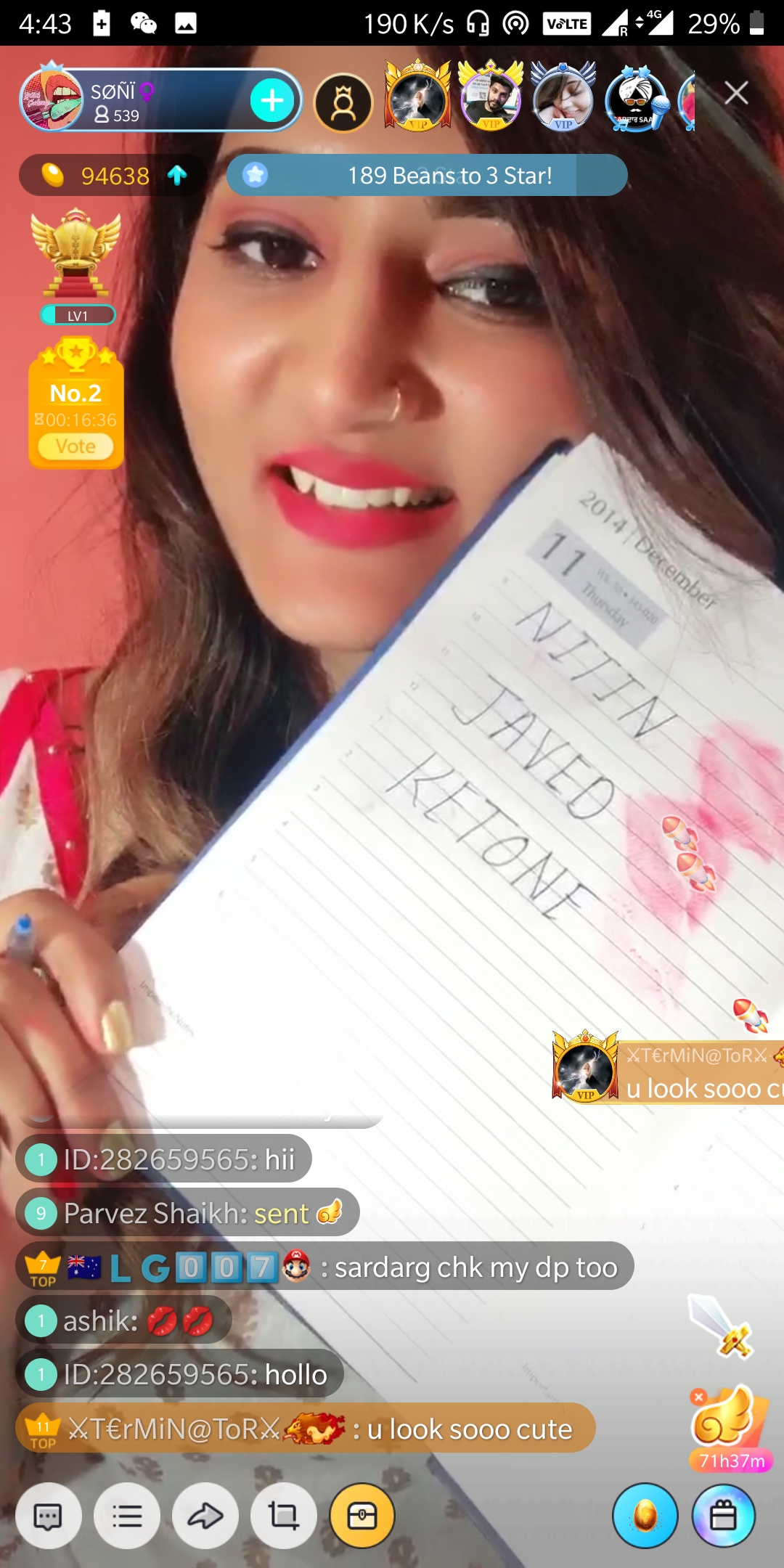

For an hour-long ‘Lipstick challenge’ on Bigo Live, women put on lip colours and talk to their viewers and ask for their votes. A person who goes by the name Soni takes creative liberty during her broadcast. “What’s your favourite colour, Nitin?” she asks a viewer. “Red,” Nitin responds on the broadcast. The streamer picks a red lip colour from a stack of lipsticks. Soni asks Nitin to send her a lipstick combo first, a virtual gift. Once she receives it, she puts on the red lipstick, writes Nitin’s name on a paper and kisses the paper. She then displays the mark of her lips next to Nitin’s name and poses for the viewer to take a screenshot. She does this for a while and climbs from rank 7 to 2 on the contest.

There are three sides to the live streaming industry triangle — the live streamers, mass users, and a top line of users who spend generously on the platform. These spenders are willing to pay to gain respect from the other two categories of users.

Some gamified platform crown high-paying users as VIPs, who tend to receive special attention and recognition by streamers.

Amal Sau, a goldsmith in Navi Mumbai hailing from Medinipur in Kolkata, spends 6-7 hours a day on UpLive and about Rs 25,000 every month on buying virtual gifts. He says he has found many “sisters” on the platform. “I spend money on Bengali sisters I met through the platform,” he says, adding that he has found friends as close as the family on UpLive. Often during his late-night broadcasts, he connects with Bengalis who have migrated to Middle Eastern countries. He also makes some money by live streaming himself.

“When you are a VIP (user) people treat you with respect,” he says. “In a broadcast with thousands of viewers, they greet you and ask you to send them gifts because they know you are important.”

Short-video platforms like TikTok make profits through advertisements and brand promotions on the platform. Among rivals, TikTok has so far been the only short video platform to attract large brands, including Shaadi.com and Myntra, as advertisers. TikTok is also working on a biddable ad offering.

“At TikTok, machine learning algorithms play a very crucial role in identifying new trends and topics on our platform, along with discovering new creators on the rise,” the Beijing-headquartered company said in an email response. TikTok, which has its India office in Mumbai, has dedicated team members who assist creators and provide them insight into how the product works and ensure that their content complies with the community guidelines, a company spokesperson said.

Lal of Talent Dekho, however, says while the Chinese apps are paying influencers they are not focusing on creating those influencers. He says recent college graduates are landing jobs at Chinese companies in India as content operation managers merely because they are active on social media. Their job is to hunt for potential candidates, as well as to scrape through platforms, identify viral content and post these on their platforms.

Also, Lal adds, having only a few influencers as a pool invites problems because the same people cannot be used over and over again. It’s a situation creators tend to exploit.

Kukreja, the one lip-syncing to popular Bollywood songs on three different platforms, says that though the platforms have rules barring creators from posting the same content elsewhere, there are hacks to game the system. A little background change or a quick change of hairstyle and she finishes her daily quota of videos across platforms in under 30 minutes. Kukreja says she is aware that this easy income is likely to be pared or even entirely stopped some day. But until then, she just has to shop for new clothes and lip sync to popular songs.