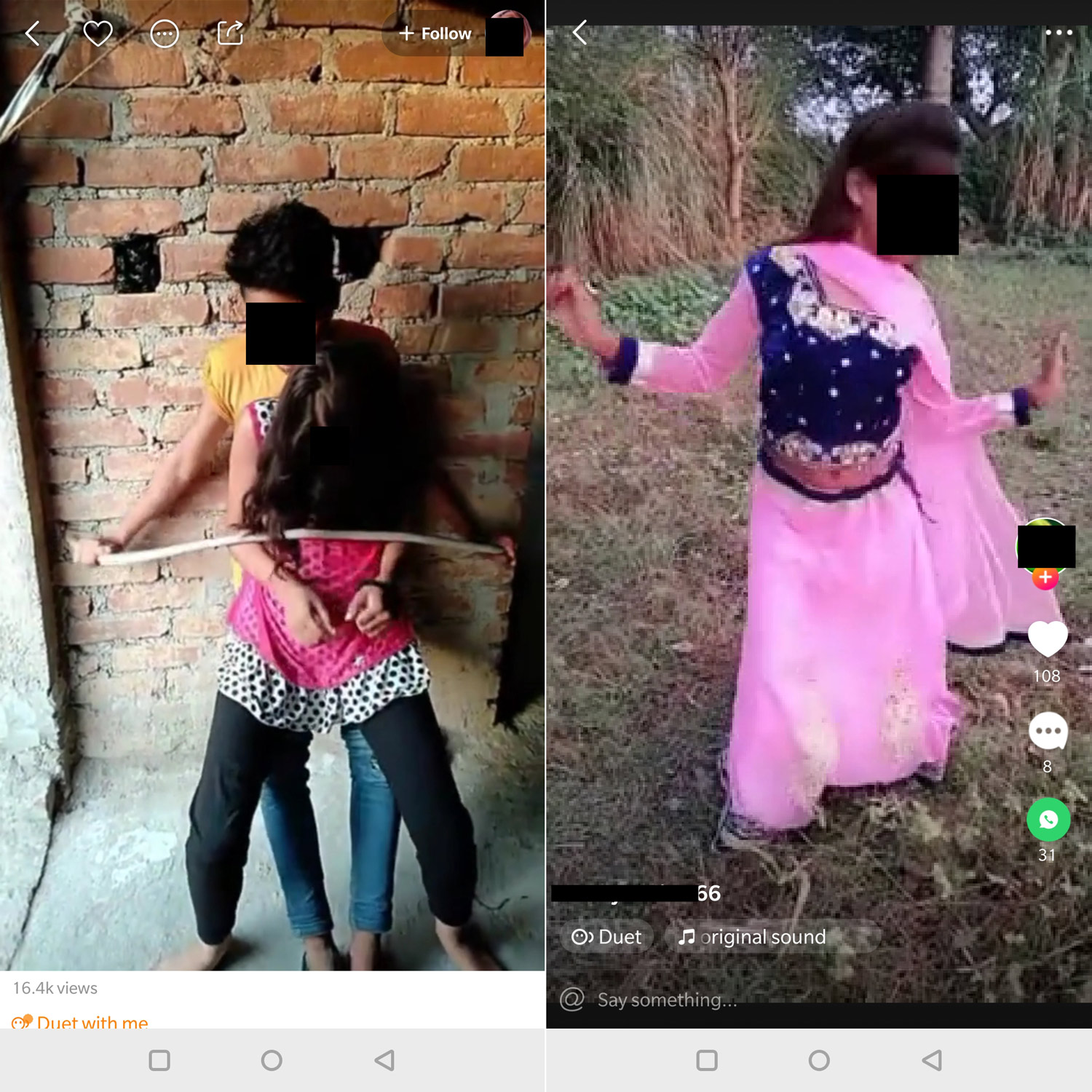

A young girl, not more than 12 years old is dressed in a bright pink lehenga and a royal blue velvet blouse. She is standing in the middle of a field and swaying her body, shaking her hips, her chest heaving as she dances to a popular Hariyanvi number that goes Meri jalti jawani maange paani paani. It’s a 15-second clip on a short video app called Kwai popular in India.

There’s another video of the same girl, in the same setting and clothes, dancing with a boy, about the same age, this time thrusting their bodies at each other to another such song.

In another video, a girl about 10, looks directly at the camera, smiles sheepishly and parrots this couplet like she has just memorized the lines: Chadar odh kay sona, takiya modd kay sona, meri yaad aye, toh jagah chhod kay sona. A man’s voice behind the camera prods her: “Aur, aur suna (sing more, more)”. She shies away saying, “Aur yaad nahi (don’t remember more).” (FactorDaily is refraining from translating the lines by the girls.)

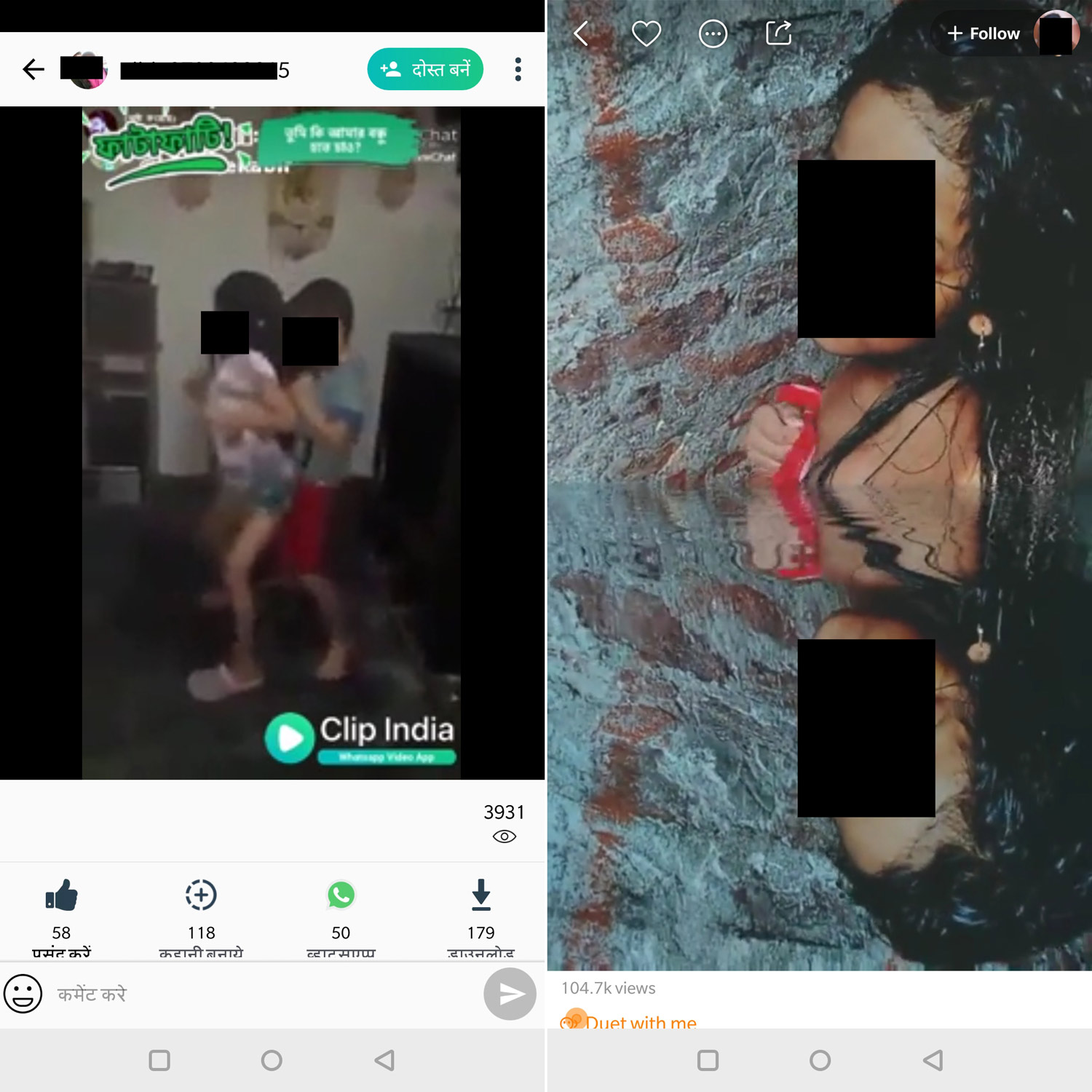

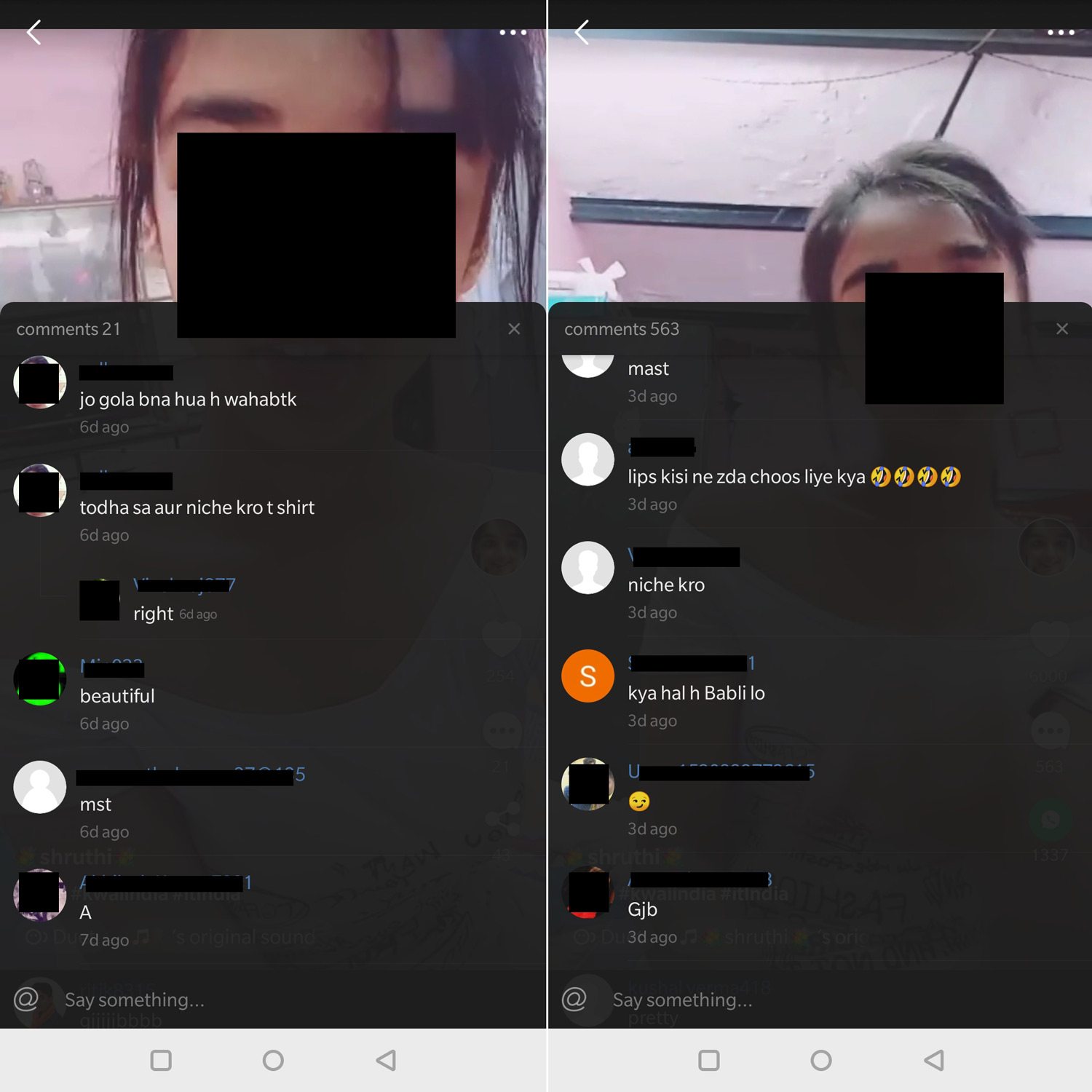

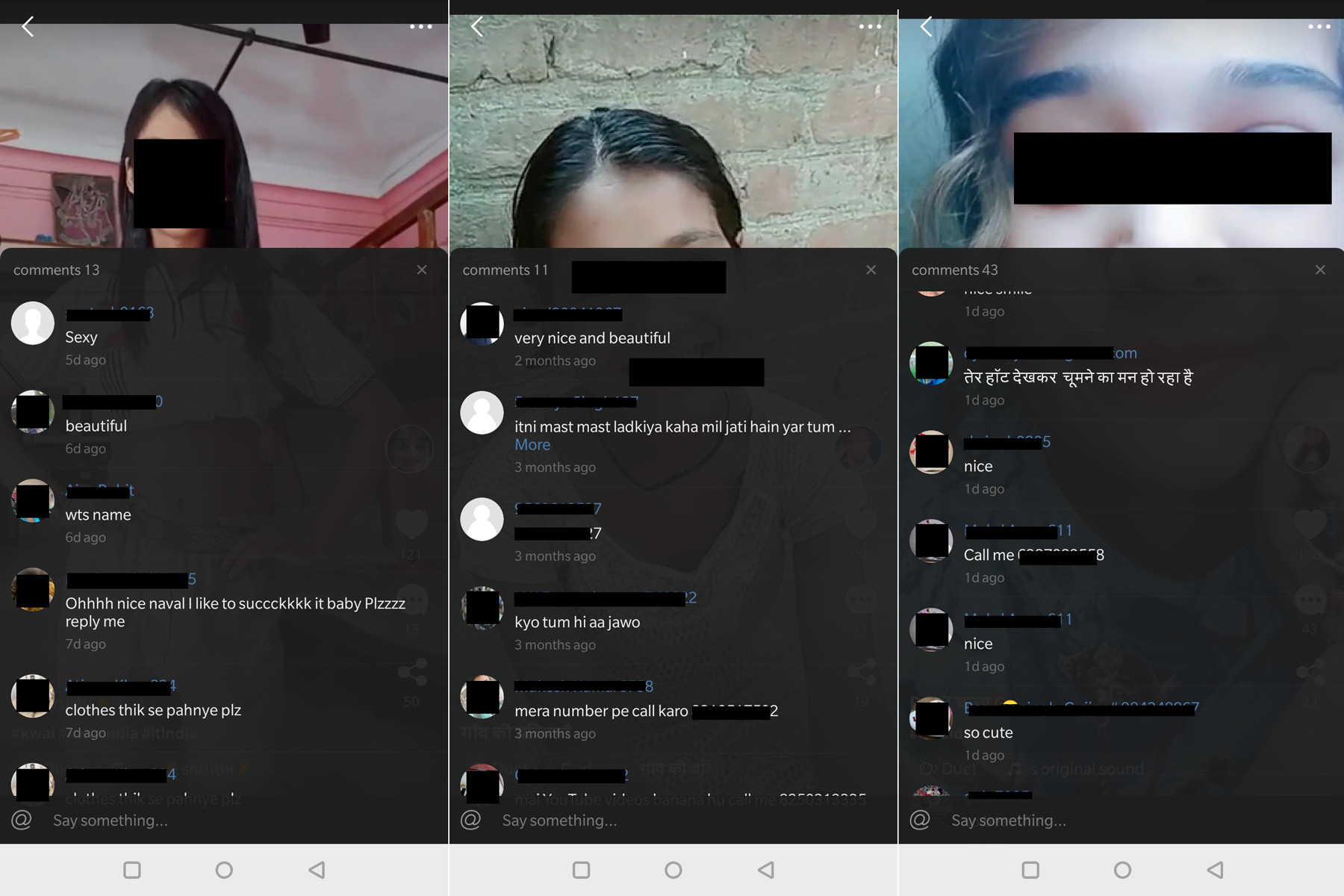

The account that has posted this and other such videos has the name Gaon ki Bachchiya (Village Girls). This account has nearly 98,000 followers and 562 videos of underage girls. Some of the videos are of girls as young as two or three years old, lip-syncing songs, dancing in an age-inappropriate manner, or doing regular chores like cooking, filling water pots, drawing water from a well, or having a meal. The comments on the posts have men complimenting girls on their body or asking for more flesh to be shown.

These videos are disturbing, to say the least. But a few minutes spent on the popular short video apps, including Kwai, Clip, TikTok, ShareIt, and others reveal the videos are only the tip of the iceberg of the underlying problem of children and preteens exposing themselves into a deep, dark world of paedophiles.

Short video apps like Kwai have been quite a rage in India and globally in the past year or so. TikTok, by Chinese giant ByteDance, counts India as its priority market had over 15 million users in India as of February 2018. With data access getting cheaper, millions of users are getting on mobile platforms every day. Apps like Kwai, TikTok and Clip aimed at lower- or lower-middle class users in India have found strong growth with demand from vernacular entertainment consumers. Kwai that counts India as its second priority market after China claims to have 10 million to 15 million users here. India-based Clip that counts Shunwei Capital as its investor had three million downloads as of December 2017.

The phenomenon of short videos that went viral among teens globally found its early roots in Shanghai when Alex Zhu and Luyu Yang, longtime friends, released Musical.ly in August 2014. The app soon became a rage among teenagers. In June 2016, musical.ly had over 90 million registered users, up from 10 million a year earlier, and had an average of 580 million new videos posted a day. By the end of May 2017, the app reached over 200 million users. ByteDance bought Musical.ly in November 2017 to combine it with its own short video app TikTok.

In many ways, the Chinese dominate the social video apps market in India. TikTok and Kwai are both owned by Chinese companies. Homegrown Clip counts China’s Shunwei Capital among its investors.

But, this growth comes with its troubles, as FactorDaily reporting shows. “Short video apps are the new breeding ground for grooming underage girls for child pornography,” said Nitish Chandan, project manager at Cyber Peace Foundation, a non-profit organisation in New Delhi that deals with child porn cases in India. In the last one year, the organisation has found an uptick in cases of child sexual abuse, harassment, bullying and blackmail where the perpetrator found the victims of one of the social video apps, says Chandan.

For over two weeks, while researching the phenomenal growth in India of various user-generated video apps, including TikTok, Kwai, ShareIt, Clip, and Vigo Live, FactorDaily came across plenty of racy content often bordering on the bawdy. Scantily clad women dancing to various numbers and suggestive sexual content is rampant across most of these apps.

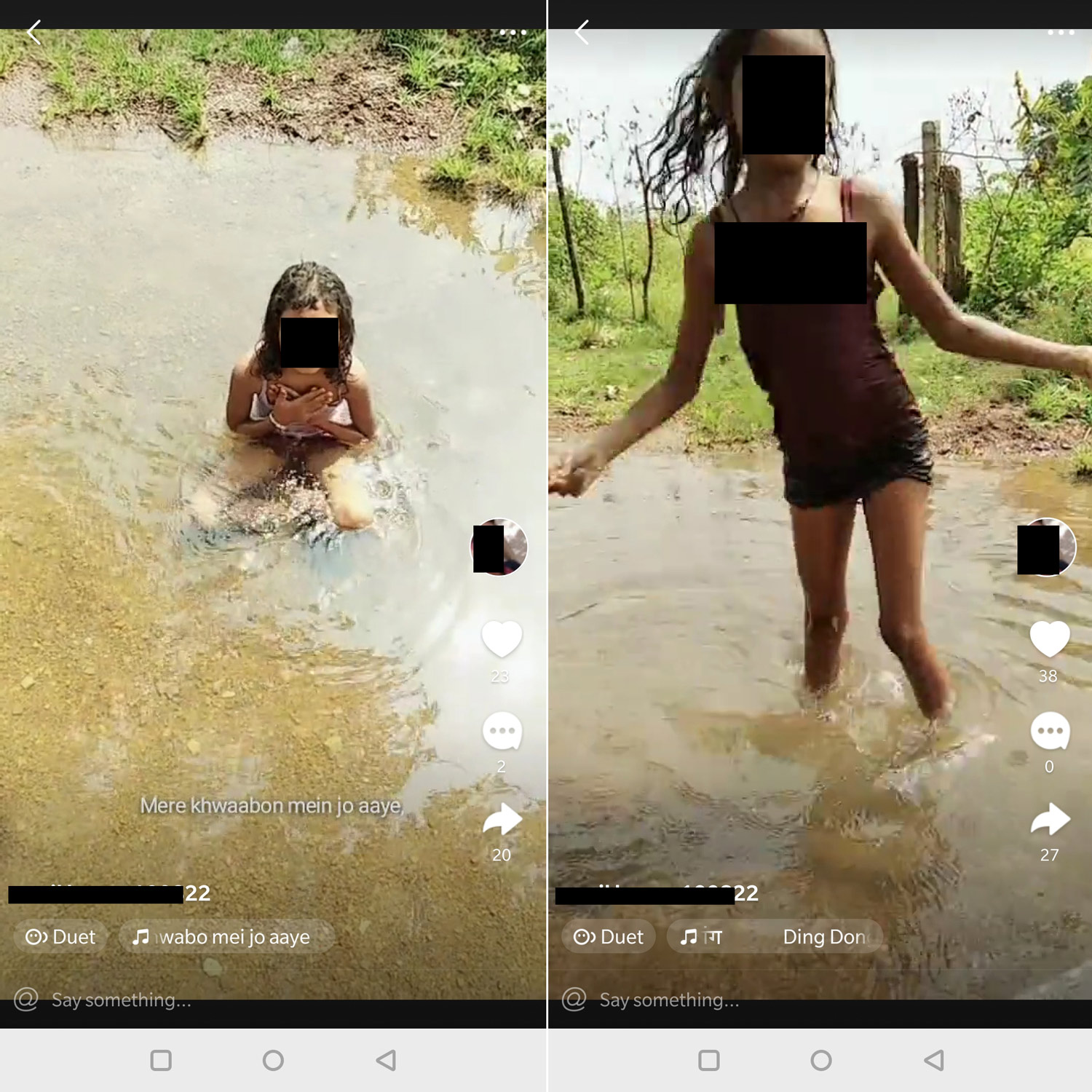

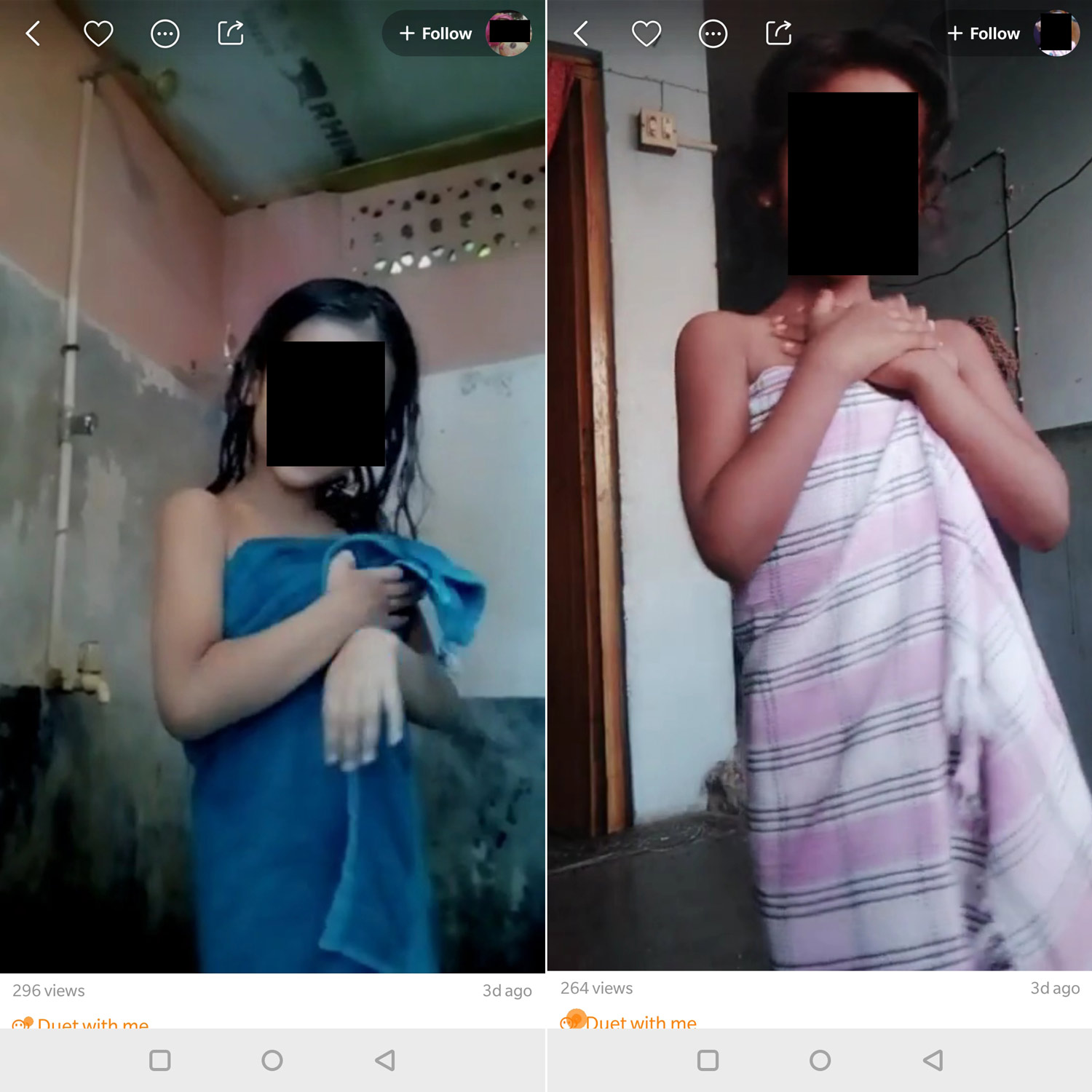

But, what alarmed us was the content – and, there was plenty of it – featuring underage girls and boys on some apps like Kwai, Clip, and ShareIt. They are seen twerking and dancing suggestively, posing in the bathroom or in a pool, lip-syncing vulgar songs, and flirting with their audience.

It is not clear if some of these accounts are owned by youngsters themselves. Biren Das, for instance, who doesn’t look older than 12 or 13 years, has nearly 6,000 followers on Kwai. She is in a white boatneck top and lip-syncs a popular Punjabi track in one of her short videos. The response of the audience is unsettling: last week, the video had 61,102 views and over 300 comments about her “hot body” and full lips with requests to take off her top. Six days later, the views had doubled to nearly 120,000 and followers almost trebled just short of 18,000. This account keeps changing its name repeatedly.

As we spend more time on the apps, what emerges on Kwai is the most disturbing. If the app is given access to the user’s location, it also indicates nearby users — increasing the vulnerability of and threat to underage kids on the app. Apart from the examples detailed earlier in this story, there are videos of girls as little as four or five years old dancing in a towel, more like teasing with the intent to drop the towel.

To be sure, the problem is not limited to Kwai, though it seems to have the most content bordering on child porn among the apps we reviewed. On Clip, a video has a girl and boy, around five years old or younger, twerking; the boy is holding the girl from behind, grabbing her towards his crotch. The video was likely taken down later. A request made to ShareIt for comment was not immediately responded to and Clip could not be reached for its responses; Kwai’s India head spoke with India and his comments are below.

Jaljith Thottoli finds the trend ominous — and, that should worry Indians because he’s an expert on how content spreads on social media and how it can be used for unlawful activities. A medical transcriptionist and activist from Thiruvananthapuram, who has busted child porn rackets on Facebook and elsewhere on social media – read our story on how he and a friend infiltrated a child porn group on Telegram in Kerala and helped the police bust it – says that the videos found on these platforms indicate a deeper problem.

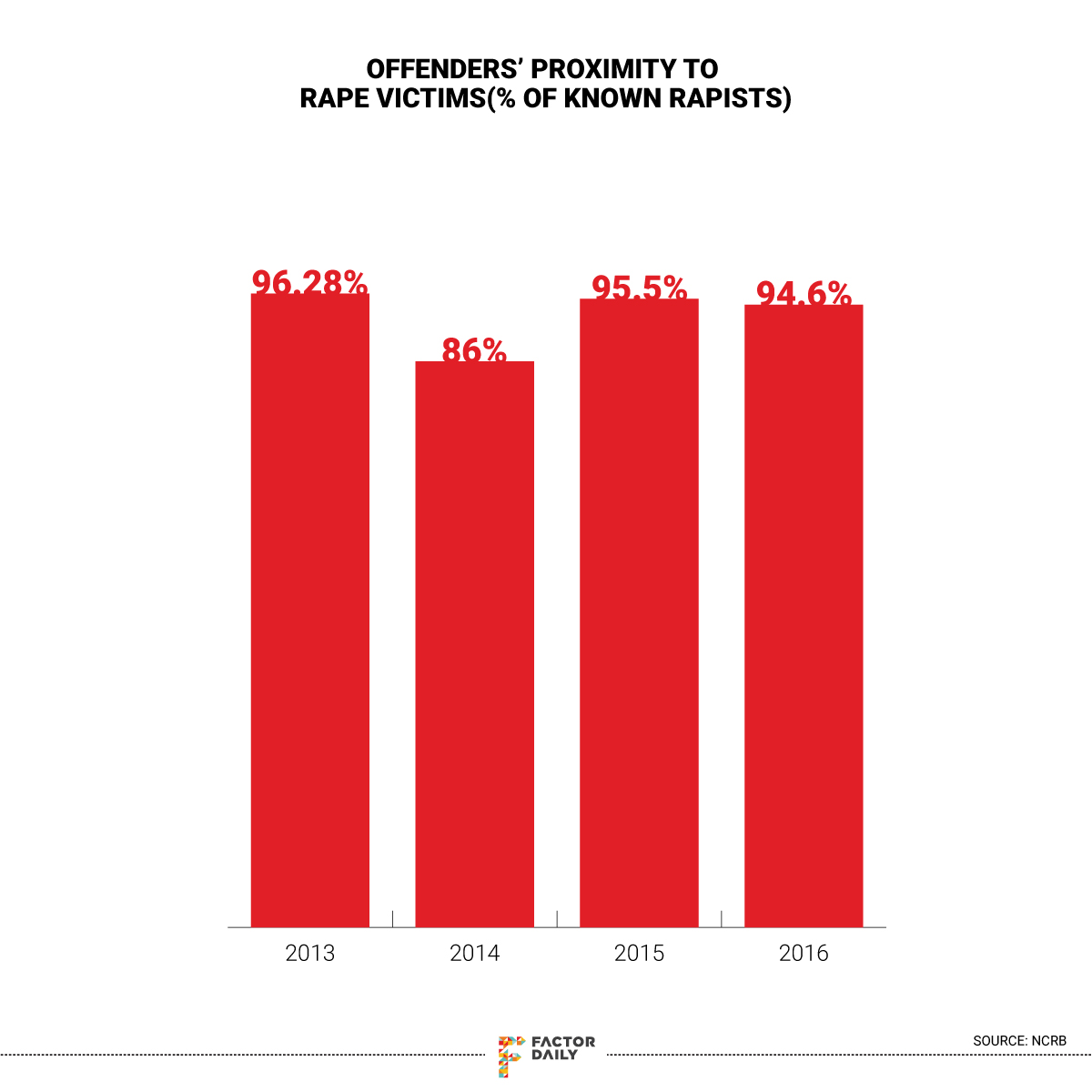

Thottoli talks about grooming as a process to make children comfortable around perpetrators. “It is like a breeding ground where a perpetrator eases a child into suggestive nudity first and then subsequently ask for other favours,” he says.

FactorDaily has previously reported on various China-based companies, including, NewsDog, LiveMe and Helo that have indicated moderation of user-generated content as a problem area. Many of these apps in the past have been ranked in the top rungs of Google Play store, indicating their popularity in India.

Forrest Chen, founder of NewsDog, an India focused content aggregator app, had told us that the company was aware of its “content problem” referring to the inappropriate and suggestive sexual content on its app. Chen agreed that NewsDog hadn’t been able to moderate the inappropriate content on the app due to its limited understanding of Indian languages and content. His team would prioritise language-based moderation going forward, he added.

The popularity of user-generated content apps among youngsters has been a challenge and its dangers have been flagged elsewhere globally, too. In July this year, Live.me that allows users to live stream a broadcast to their followers deleted over 600,000 accounts of children under 13 after a TV news channel talked of the dangers of paedophiles exploiting children.

Back to India and Kwai. Kwai app asks users for their phone number and Facebook credentials or email access to log into the app. Though this information is not displayed on the profile, there is a provision on the app to send a private message to any user — again, making it easier for someone to contact another person on the app.

Kwai, like most other apps, is designed to get users hooked to the platform with a simple-to-navigate interface. Once a new user registers by verifying a contact number, it takes the user to the “trending” section of videos: four vertical thumbnails take up the rectangular screen of the phone. A regular user is plunged right into a trending video, most likely based on user’s previously established preference. Scrolling becomes an endless feed. Before you know, you have spent minutes and hours viewing lip synced movie songs, dancing kids, and monkeys imitating humans. The design of the app is very similar to that of TikTok, the Chinese app that had 500 million monthly active users globally as of June 2018.

Since the app depends on user-generated content, it runs contests and campaigns to encourage more local content. Popular content on the app is generated through campaigns like ‘Act like Amitabh Bachchan’, create a dance video using #BalleBalle, mime your favourite Bollywood movie dialogue, or post a Mehendi video. Some of these contests also announce results and rewards for the best videos. The prize money on these videos ranges from Rs 30,000 to Rs 1 lakh.

Ganta Murali, head of Kwai India, says that the platform’s differentiator is its content which is not just limited to entertainment through aggregation. The platform, he says, is focused on adding local content on the platform – content that its users will have a better affinity towards.

“Our primary goal and focus right now is to target North Indian languages and people,” says Murali. In future the company may have a dedicated version for south Indian languages, he adds.

The company also educates some of its users in order to create local content. It holds live video training sessions with some users training them to create videos. Murali says that accounts that create popular videos which receive more views and comments are rewarded with monetary rewards. Some top India users earn up to $400 in a month, he says.

It is clear that there is significant interest out there in inappropriate content with underage children: enough for many subscribers to leave their contact numbers in the comments asking the account holder to get in touch. They are brazen: the numbers can be seen by anyone who logs on to the app.

FactorDaily reached out to one such person who had left his number on a comment to one such video. Ravi Yadav says he is a tea-seller in Chennai and hails from Darbhanga in Bihar. I tell Yadav I’m writing about Kwai and need some information. A little hesitant and surprised by the enquiry, he tells me he’s a very busy man and yet finds time to do things he likes. He says he is not a regular on Kwai app but uses it during the easy hours of the day. About his choice of content on the app, he says he likes “bewafa” category of videos and songs. Bewafa in Hindi translates to unfaithful but Yadav is referring to sad or heartbreak content common in Indian cinema and TV shows.

It is clear he doesn’t like our conversation. “Do you need anything else or is that it,” he asks. A minute after he hangs up, he calls back to ask: “How did you know to contact me? I’m surprised because I try as much as possible to stay away from women.” He then suggests that I call him the next day. He will do his homework on Kwai app in the meantime, he says. My calls go unanswered the next day.

Kwai’s Murali says that to ensure that the content on the platform stays healthy, the platform uses both automatic and manual review systems to monitor all user-generated content. On the China version of the app, Kwai has recently released a parental control function that blocks unsuitable content to protect children and youths.

Murali adds that much of the content generated on the platform featuring underage kids come from fake accounts. By fake accounts, he means accounts that are either aggregators of such content or accounts managed by parents or a relative of these kids.

“There is a continuous audit to monitor content on our platform. If there is adult or inappropriate content featuring kids, it will be taken down,” he insists. For more details, Murali asked for questions for the Kwai corporate communications department, which were sent but have not been answered at the time of publishing this story.

The content moderation team for Kwai sits out of Beijing. It’s highly unlikely that this team will be able to detect an inappropriate couplet that a clueless girl narrates on a video.

All this hasn’t solved the content challenge for the company. According to a rival startup founder, the app has pulled back on its marketing efforts in India to focus on getting the product right. This person said Kwai realised that it needed to tweak its product to suit the vernacular audience in India and also understand the cultural nuances.

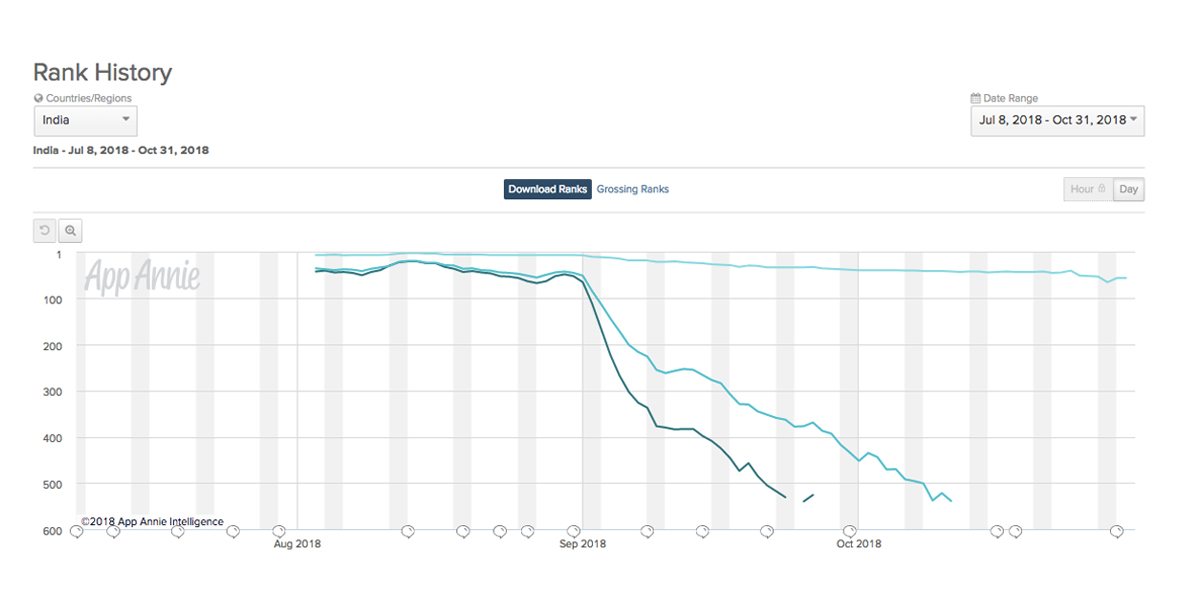

AppAnnie data also suggests that Kwai that started out huge in India around August where it gained a majority of its 10 million to 15 mn subscribers but it then dropped down drastically in October. (See AppAnnie graphic.)

It’s important to note that Kwai cannot be dismissed as just a cheap and shady app trying to pass overtly sexual content under the name of entertainment.

Launched in 2011 and headquartered in Beijing, Kwai has over 700 million global registered users and more than 120 million daily active users in May. TikTok, in comparison, was smaller with 500 million monthly active users in July. Kwai is backed by Chinese internet giant Tencent Holdings and ranked as the most downloaded video social sharing app in South Korea, Vietnam, Philippines, Russia, Thailand, Indonesia, and Turkey in May this year.

That said, the notorious content on the app has also been a problem in the past elsewhere. Earlier this year, the platform removed over 430,000 videos that flouted Chinese regulations and blocked more than 25,000 accounts just this year, after being criticised by Chinese authorities for content that was “vulgar, violent, gory, pornographic and harmful”.

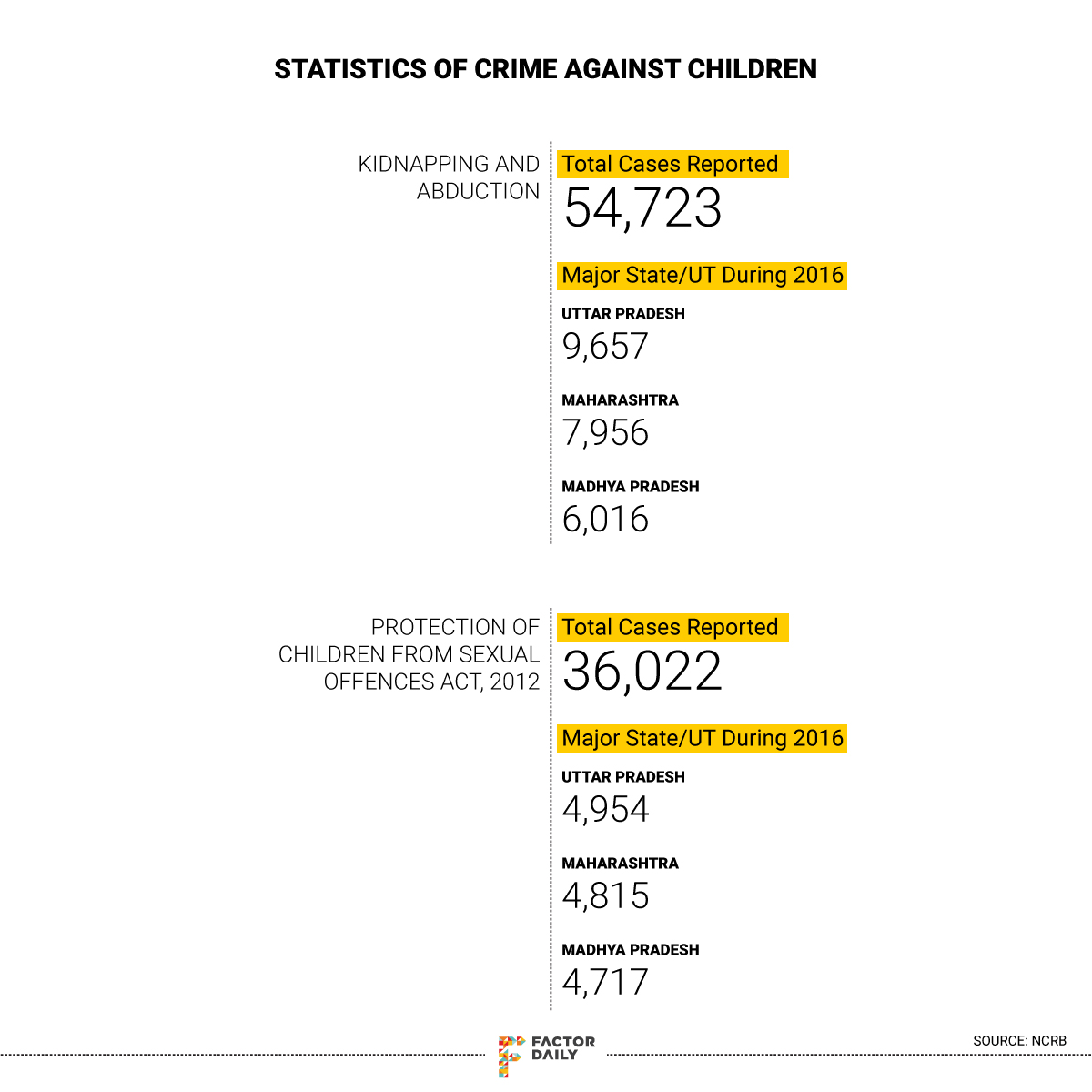

Cyber Peace Foundation’s Chandan says that child porn is a deep-rooted problem in India and the content on Kwai is just the tip of the iceberg. “There are stats that show that Asian kids are the most in demand for child pornography,” he says, adding that the northeastern states are most affected by the perpetrators.

Chandan says that even though the National Crime Records Bureau doesn’t capture details of such crimes such under the app or service used, Cyber Peace Foundation has approximately received 148 cases reported on child harassment that originated from social apps. These are only cases reported to the foundation, he hastens to add. There could be thousands of other cases that go unreported.

Social video apps are immensely popular among paedophiles to find and groom targets. Chandan says in the past year he has encountered many cases where the perpetrator posing as a kid reached out to the underage users through gaming apps like PUBG, which Mint newspaper described as a phenomenon in India.

Gaming apps are addictive and are rely on gamification of the platform for monetisation. An addicted user is ready to watch ad videos, sends referrals, fills surveys only to continue playing the next level of the game. Sometimes that’s not enough and a user ends up paying money to buy more “lives”.

Chandan says paedophiles exploit this addiction and offer to pay up for a kid who has no lives left to continue playing the mobile game. They soon build a rapport with the kid and after reviving the kid on a game couple of times, they start asking for favours in return. It begins with only asking for their contact number first and then slowly getting to know about where the kid lives and other details. In some cases, the kids raise a red flag and the parents report the cases. In most other cases, they don’t.

Some gaming-like challenges play out on social apps, too. There’s also another trend of sending a video to a bunch of kids asking them to imitate an adult and send their video back. Chandan says there have been cases of young girls masturbating and sending these videos to a friend they met on one of these social apps.

“Most of these young girls don’t know what they are doing. They think they are completing a challenge and are going to win a contest if they do it well,” he says.

Apps like TikTok, Kik Messenger, a chat app called Omegle, and Holla, a video app that randomly matches people on live video chats are popular among underage Indians and have found to be hunting grounds for paedophiles, points out Chandan.

The legal age prescribed to be on most of these social apps is 13 years. But there are many instances of kids younger than 13 having access to and posting their videos on apps.

In the over 120 such accounts with content on underage girls that FactorDaily reviewed, ‘‘RaaZ बन्ना’ ‘ stood out. The girl looks like not more than eight years old. From her photos, it is evident that she has access to her mother’s or an adult’s make-up kit. She also has more than 31,500 followers on Kwai. A quick glance through her 591 posts has her smiling coyly, blowing kisses at the camera and sometimes crying lip-syncing a song of her long-lost love. It is reasonable to assume that her parents are not aware of her Kwai profile. But the comments on those posts reveal that paedophiles and potential predators are.