Around 200 milk farmers from Indapur village, some 140 km southeast of Pune in Maharashtra, and surrounding areas are sitting under a pink-and-white shamiana on a sunny, winter afternoon in November. It is an awareness workshop for what data tracking and genomics can do for milk farming but the buzz is more around when dairies will raise milk procurement prices.

As veteran veterinarian Abdul Samad strides to the stage to address the gathering, some in the crowd are expecting a political speech. Dr Samad doesn’t disappoint. He starts with stagnant milk prices but quickly segues into a solution within the reach of farmers: “Stop agitating about milk prices and start focusing on improving productivity and profits. Have you ever cared for where the bull semen is coming from when you do artificial insemination for your cattle?”

The switch from politics to semen quality is a hard swerve and there are amused murmurs in the audience.

But, reality stares them in the face.

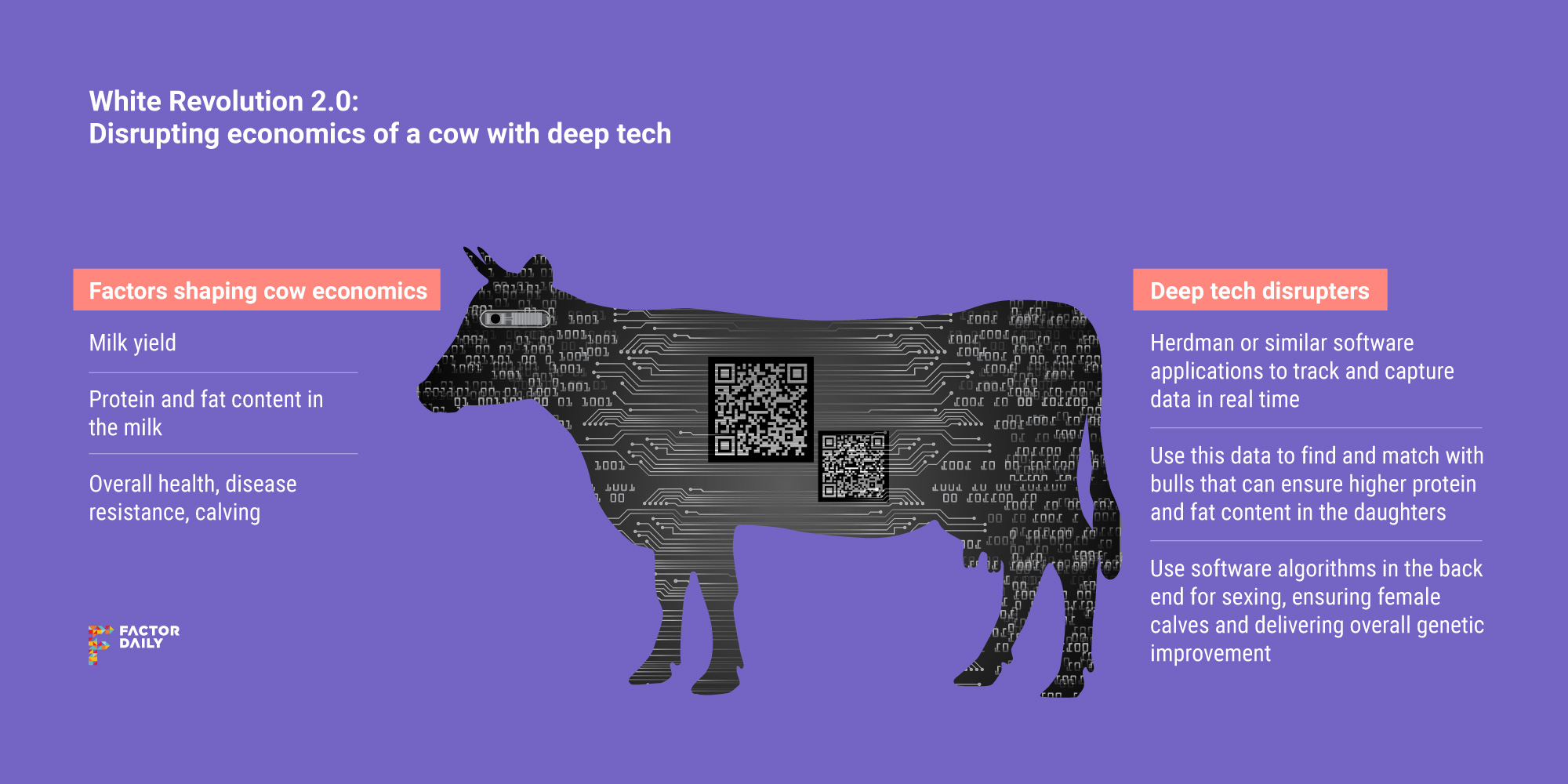

Milk prices in India rose three times in the decade to 2015 but have plateaued since. This has led to Indian diaries and the farmers they procure milk from looking for solutions to rein in costs and at the same time raise milk output from their bovines. For a country that produces some 155 million tonnes of milk a year, the big question is how to increase the productivity of the Indian cow from the current average of 1,200 litres a year to averages in countries such as the US and Israel: around 3,500 litres annually. (One litre of milk is approximately 1 kg; it takes 1,000 milk litres to weigh a tonne.)

“Even a small shop owner keeps all the records, data. Where is your cattle data,” asks Dr Samad, who retired as dean of Bombay Veterinary College in 2010.

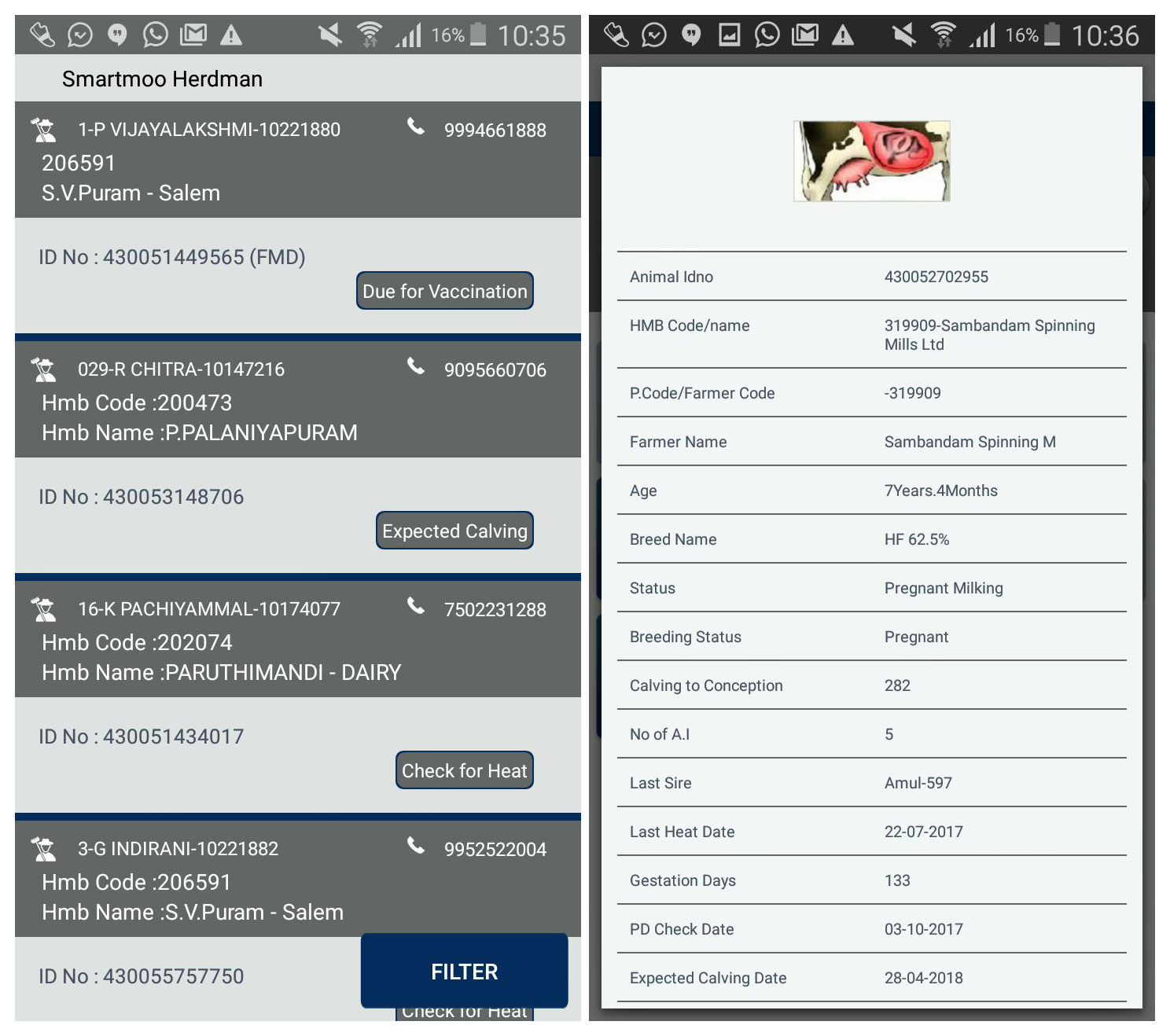

With more than four decades of work behind him, the vet knows what he’s talking about. In 2002, Samad, along with a software engineer Prashant Murdeshwar, co-founded a company called VetWare. It now offers a mobile-based and easy-to-use app, called Herdman, for farmers to capture cattle data using QR codes on the front end. That data is used to produce insights about cattle health, matching bulls to bring about genetic improvement, and even milk production forecasting. These insights are delivered in the local language to milk farmers and the vets looking after their herds.

The potential of the software and genomics is immense in the fragmented India milk farming sector, where some 120 million farming families are engaged in cow and buffalo rearing, according to the Indian Agricultural Census. If they can double milk yield, it will have large implications for nutrition in India, milk and milk product exports, and generation of new national income that is better distributed among the country’s 700 million farmers.

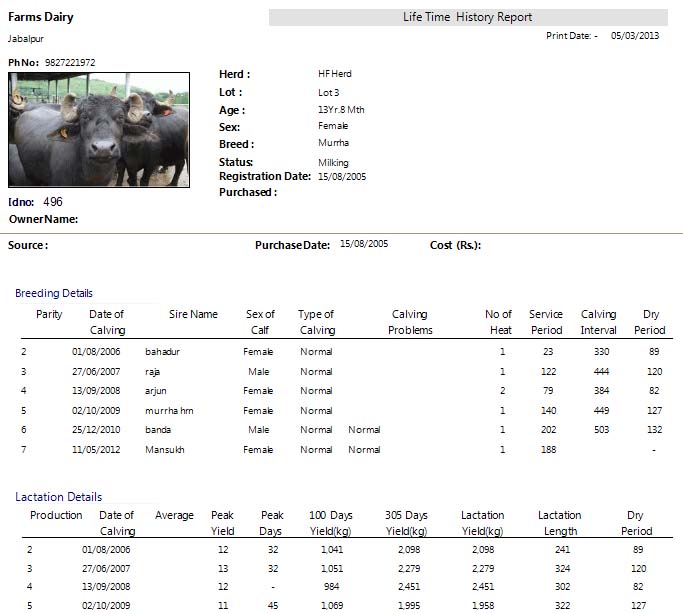

The repository of information that Herdman covers includes feed data, days to puberty and calving, weight, health and disease tracking, milk yields, quality of milk etc. for each of some 240,000 cows and buffaloes on the software across India. Chitale Dairy from Sangli and Hatsun Agro in Salem are the pioneers of adopting techniques wrapped into Herdman.

Hatsun wants to deploy the solution over one million cattle in two years time. Larger dairy operations such as Amul have their own tagging and data collection solutions; more on that later.

Many in the crowd at Indapur are clueless but curious about how tracking cattle data using mobile phones can help them double milk productivity. “How long can we remain cry babies hoping the politicians will help address the pricing issue?” asks Sudhakar Mane, who has a dozen cows in Indapur. “This doctor is saying we can even correct the problems in our current cattle by getting semen from bulls who can ensure the next generations are far more productive.”

“But how? Hope this isn’t some kind of a gimmick,” asks Ganesh from a nearby village. He goes only by his first name.

The answer, according to Dr Samad, 64, lies in genomics apart from using software tools to ensure farmers do not make blind decisions and mistakes in managing the health of their herds.

“If you look at right from 1952 until today, we have hardly made any difference as far as the national average is concerned. We must talk of the national average, not some isolated examples of animals giving 20-30 litres of milk every day,” says Dr Samad.

Herdman combines intelligent tracking of animals with genomics big data to help milk farmers make informed decisions about breeding their cattle with the right bull.

“Breeding is about selecting good animals and leaving out bad animals. Unless you have records and the data, how would you know where the good animals are,” asks Dr Samad.

ABS Global, a US cattle genomics company, is tapping into the cattle big data by relying on Herdman, apart from its own software algorithms that do intelligent matchmaking between cows and buffaloes with bulls to give birth to high, milk-producing female calves.

“Software such as Herdman help keep the data accessible. For instance, when a farmer is evaluating a cow to buy, he can scan the QR code tag and read all the historic data to make a more informed buying decision,” says Arvind Gautam, the head of ABS’ India operations. To be sure, ABS is not the only player in this space – its rival Sexing Technologies is also active in India, as are World Wide Sires and Genex, also from the US, and Semex of Canada.

Larger Indian dairies such as Hatsun are designing breeding program for its over 300,000 cows and buffaloes by figuring out dry periods for each of them. This information, too, comes from Herdman.

“If for instance, Hatsun gets to know that March is when most of its cattle will be in dry period, it can redesign the breeding program in a way that there’s a healthy mix between lactation periods to ensure milk productivity doesn’t suffer,” says Gautam.

A foreign animal husbandry expert working with an Indian dairy sums it up best when he talks about Indian dairies “black box” problem. “Every day we know exactly how many farmers poured milk and the quantities they poured…. but we have absolutely no idea how many cows it took to produce that milk,” he says, requesting anonymity because he was not authorised to speak with media.

As a result, generic and vague recommendations were made to farmers and animal health services were “totally reactive, rather than being proactive to assist farmers to avoid animal health problems,” says the expert on an email.

His dairy has seen benefits accrued for not just its animal husbandry team, but also for the milk procurement team and, above all, the farmers, he adds, summarising the benefits below.

By tagging and recording animals in a Herdman database the animal husbandry team has now the ability to:

Much of the information can now be reviewed in a unified manner and messages can be sent to farmers by SMS or other electronic methods.

The milk procurement team has the ability to:

For the farmer, the benefits are:

Experts such as Marcia I. Endres, a professor at the University of Minnesota’s animal science department, say the key is to ensure that smaller farms in India get data at a low cost, which can then be used to improve operations. Endres has studied Dr Samad’s software.

“An old adage says “you can’t manage what you can’t measure” and the software collects information that the farmers and their veterinarians did not have before,” says Endres.

Once an animal is registered on Herdman, current health and any historical data available are captured. From thereon, each event including heat period, artificial insemination date, pregnancy, calving, vaccinations, treatment of any diseases occurred and, finally, the milk yield across different lactation cycles is recorded.

For every animal registered on the system, farmers have to pay Rs 50 annually or use it free but be served local ads.

After Dr Samad’s session in Indapur, the farmers move to a hall on the first floor of a building nearby. The room is full and farmers such as Mane are now prepared to get the final tips.

“How can India double milk production by 2026,” ABS’s Gautam asks the audience.

Maintaining records of cattle health and their family history or parental matching is only the starting point. It takes years before results start showing from genomics-based breeding.

ABS’s genetic mating software matches cows with bulls using dozens of parameters and based on expectations of a farmer from the next generation calf. Depending on the cow they have and the problems they want to rectify, farmers can demand anything from more fat content in the milk to better rudder placement, or even set a target of 20 or 30 litres milk daily.

After these requirements are captured, the software algorithm runs search queries in its database to find an appropriate set of bulls and displays the result by ranking them according to their effectiveness. This matching process, which involves running hundreds of potential combinations, takes less than 30 seconds.

Gathering all the genetic data on bulls and cows is such a massive effort that Genus ABS India, a joint venture between ABS Global and Chitale Dairy which started groundwork in 2010 in Bhilwadi, Sangli, has selected only a few breeds to start with: Murrah, the buffalo breed, and Gir and Sahiwal for sire.

“The more data we feed into the system, the better it gets. As data grows, its reliability too will improve,” says Gautam. Companies such Sexing Technologies and ABS have been described as the Monsantos of the dairy world for the genetic-level potential they hold for the $350 billion global dairy industry.

What Dr Samad’s Herdman software does is solving only one tiny piece of the grand puzzle. For India’s milk productivity to double by 2026 for instance, it will need to combine all genetic big data of cattle with a scientific breeding program.

Like dairy farmers in the US did. “The high productivity per cow in the USA has a lot to do with improvements in genetics and management that could only happen because we had records on how the cows are producing every day or at least once a month from testing, allowing producers to select the best animals and improve management practices by being able to measure the results,” says Endres, the US professor.

India lags countries such as Brazil too.

“Until 1985, they (Brazil) were doing cross-breeding like we are doing mostly today,” says Dr Samad. “Then they realised cross-breeding is not the answer for tropical countries like theirs.” Recording data was followed by identifying genetically superior animals.

Slowly, the results started showing. Brazil has two kinds of herd system: one is where the cows are free-grazed and the other where they are stall-fed. For the grazed ones, the average yield today is 4,000 litres to 4,500 litres of milk annually. The ones that are fed specific nutrients along with feed in stalls, yield 8,000 litres and more, according to Dr Samad.

Not just that. Cows with breeds of Indian origin dominate the Brazilian market. The top nine breeds of bulls, including Ongole from Andhra Pradesh, account for nearly 80% of milk production in Brazil were taken from India, and improved upon genetically. According to agricultural economist Devinder Sharma, a descendant of Gir breed of cows from Gujarat has recorded 60 litres of milk a day in Brazil.

The US has raced even further ahead — the “connected cow” is enabled by everything from real-time sensors to robotic milking.

“More recently we have seen growth in the use of technologies such as individual cow sensors (for rumination, activity, feeding and resting time, temperature, etc) and automation (robotic milking and automated milk feeders) which provide even larger amounts of individual animal data to be used for health, reproduction and performance improvement,” says Endres.

ABS’s efforts have led to creating a league table of India’s top performing bulls. “Bahubali, the bull, is more popular in our community than the movie,” says Vikas Dandelkar, a farmer in Bhilwadi, tells FactorDaily at the local milk collection centre.

The semen of Bahubali, a cross-breed Murrah buffalo bull in Sangli, is much sought after — each of its semen doses costs Rs 150 versus Rs 30 for a normal bull insemination dose. Placed No. 2 on India’s league table for bulls by semen quality, it has exceptionally high dam yield of 5,586 kg per lactation with well over 7% fat.

“Since there is no genomics in buffaloes or indigenous cattle breeds, selection of bull is as per mother’s milk data – higher the better,” says Gautam of ABS. There are 96 other bulls on the league table including Holstein breed Stryker and Brute, Jersey breed Preet and Tyson, and two other Murrah buffaloes Redhu and Maharaja. They are all based on a farm in Bhilwadi at Genus ABS lab.

Chitale Dairy has seen its milk productivity improve since when the genomics lab was first set up in 2010. From around 350,000 litres a day three years ago, Chitale now procures over 750,000 litres daily in Bhilwadi, Sangli. And, the improvement has come by keeping the number of cows and buffaloes, around 100,000, mostly unchanged.

“To achieve this level of improvement, having big data is a must,” says Vishwas Chitale, director, Chitale Dairy. “[Results with] genomic selection is only possible with recording.” Some of the improvement in yields at Chitale Dairy are due to other interventions such as feeds.

Herdman is not the only software being used by milk dairies and farmers in India. From National Dairy Development Board (NDDB)’s own software solution developed in-house to products from newer technology startups such as Stellapps, there are enough options.

NDDB has been actively using software in data capture, genomics and even to ensure a balanced diet for some 2.7 million bovines.

“The country’s breeding programme depends on this,” Niraj Prakash Garg, a deputy general manager at NDDB’s IT division told FactorDaily at Anand, Gujarat, in December last year. He was referring to NDDB’s Ration Balancing Programme aimed to ensure balanced, personalised fodder for nearly 2.7 million cows and buffaloes across 40,000 Indian villages.

In March this year, NDDB also launched a new Android app for tracking and managing genetic improvement of cattle using artificial insemination. The plan is also aimed at capturing big data on millions of bovines and over 15 million milk producers. “The key output is you’re able to identify which bull is good,” says Garg. Extra emphasis is given on the ration program, which helps farmers optimise feed for their cattle, personalised for each animal. By December 2016, over 2 million cattle were already part of the diet program with each of the milk farmers saving Rs 30 every day per animal because of the software, according to Garg.

NDDB’s scale of operations dwarfs all other dairies. During 2015-2016 for instance, the cooperatives registered under the NDDB collected around 15.58 million tonnes of milk from cows and buffaloes under its ration programme. “It’s not a pilot or an experiment, but a full, mainstream program with demonstrated benefits,” says Garg.

For Dr Samad and ABS, Bhilwadi’s Chitale Dairy has been a sandbox to experiment with software to genomics. With those experiments maturing, Samad’s Herdman software is now evolving with bigger dairies such as Hatsun in Chennai, which has some 220,000 cows on the software. Hatsun Agro Products, a listed company, runs India’s largest private dairy operation.

“If you are able to manage the data, you can easily increase the milk yield without doing anything else by 20-25%, only because you are preventing management losses. Otherwise, you don’t do pregnancy tests, you come to know after six months and by then you, as a farmer, have lost half the year of precious time,” says Dr Samad.

By combining the operational data about cattle with genomics on the other end, the benefits could be far more.

“It keeps on calculating and tracking performance indices of health, fertility and milk production of each animal and keeps flagging the problems and prompting for appropriate interventions,” says Dr Samad. “We find that 90% of the time, it is not the infection but it’s the management (or lack of it) which is causing the problem.”

Still, both Gautam and Dr Samad agree that the real benefits of genomics will take at least a decade to start showing on a sizeable scale.

There are issues of broken economics to deal with – how to cover additional expenses such as the cost of fortified feed and that of sexed semen (Rs 150 for a dose but an insemination may take multiple attempts) while milk prices remain stagnant. Pradeep Balhara, the owner of 1,000-cattle Balhara Dairy in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, says, “You can’t talk vitamins and other nutrients if the basic, staple food is missing.”

Among the early users of Herdman – Balhara’s been using it for over a decade – the biggest benefit for him, he says, has been the ability to plan the breeding cycles of different animals. “It means a lot for a dairy like us, we can avoid the dry seasons,” he says.

It’s moving the needle for small farmers, too. Mahesh Dhondiram Yesugade, a milk farmer in Sangli with one cow, started using Herdman two years ago and followed its advisories. He says his income increased by Rs 200 a month in the first year and in the latest month by Rs 1,000 — an increase of some 50% from the Rs 2,000 he used to make earlier. “I now plan to buy another cow and plan breeding in a way that there’s no dry season,” he says.

Farmers like Balhara and Yesugade are critical to the success of the Second White Revolution, as the nationwide dairying programme of the 1970s and 1980s is referred to. The benefits of data- and genomics-driven dairying will need showing, not telling, says Endres, the University of Minnesota professor. “We need to have the early adopters, otherwise a technology will not be successful. Cultivating those early leaders is important.”