The draft legislation is expected to be ready in about a year.

A draft data protection law, which is at the core of the Indian government’s stance that Aadhaar does not violate citizen privacy, will have user consent as its mainstay with a few exceptions.

The draft legislation is expected to be ready in about a year.

This was revealed in interviews with a member of the committee set up by the government to come up with the draft framework — B N Srikrishna, a former Supreme Court judge who is heading it, and a second person with knowledge of the committee’s thinking.

Aadhaar is India’s unique citizen ID project that has enrolled over 1.17 billion people. It has run into controversy over the way it is designed — a central repository of citizen information, including biometrics — and the potential for misuse of the data such as mass surveillance by the state.

The proposed “data empowerment and protection act” will make obtaining user consent mandatory for data collectors and ensure the framework makes it easier for everyone to obtain the consent wherever required.

“Just the way nobody can move money without your consent, similarly, no one will be able to move your data,” the second person said. “Unconsented flow of data will be illegal.”

Justice Srikrishna said India needed a privacy law as of several years ago, referring to a fight between Blackberry and the Indian government, which included threats of a ban and got resolved after the Canadian phone maker allowed New Delhi the right to intercept emails and messages except on its enterprise server.

“That was a dangerous decision. We shouldn’t have sloped down into it. We didn’t have a law,” he said in a phone interview from New York, where he’s attending a private event.

Data security is going to be very important for India as a country and its people, he said. “The point is this: data needs to be collected for private purpose or public purpose. For getting employment, checking into a hospital or anything else. But, then there are other questions: are you collecting data with the user’s consent, what purpose are you collecting it for, how long will you keep, when will you destroy it…,” said Srikrishna, who also heads the Financial Sector Legislative Reforms Commission of the government of India.

“These are the essential things to look into, especially after the Supreme Court judgement. Whatever we do [on the data protection law] has to be consistent with fundamental rights,” he added.

On Thursday, August 24, a nine-member bench of India’s Supreme Court ruled that privacy was a fundamental right under the Constitution with reasonable restrictions. It further said: “Data mining with the object of ensuring that resources are properly deployed to legitimate beneficiaries is a valid ground for the state to insist on the collection of authentic data… But the data which the state has collected has to be used for legitimate purposes… and not unauthorizedly… .”

The Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), the agency responsible for the Aadhaar project, has interpreted this as grounds that there is no challenge to the citizen ID. But, this will depend on how a smaller bench of the Supreme Court, which is hearing other legal challenges to the unique ID project, interprets the privacy judgement on citizen rights as far as Aadhaar is concerned.

While the data collectors will be barred from sharing data without user consent, the proposed law provides for exceptions, too. “In instances where regulators such as TRAI and RBI believe sharing is required in public good, the law will make exceptions,” the second person said. “Regulators will decide when a user is obliged to share data.”

TRAI, the country’s telecom regulator, is short for Telecom Regulatory Authority of India. RBI or the Reserve Bank of India is its central bank.

In fact, TRAI, earlier this month, floated a consultation paper on privacy in the telecom sector. An April 2016 paper by the RBI on peer-to-peer lending covers data privacy in financial models.

The proposed act will define the scope for consent collectors, data providers, consumers and auditors, and establish each one’s obligations to ensure data protection overall.

“The (proposed) law separates data producers from data consumers.”

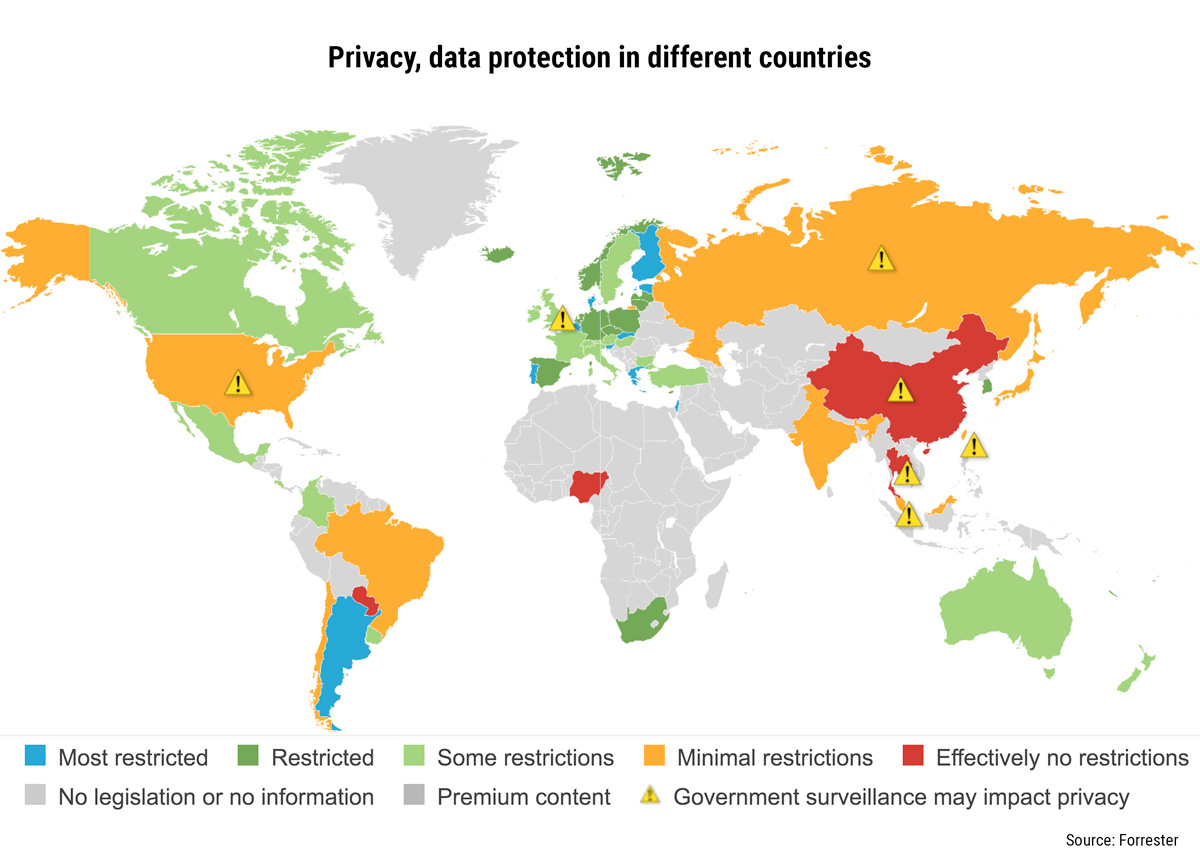

Justice Srikrishna said data protection laws internationally present some inputs for India’s draft law. There are models that India can benefit from, he said. “For instance, in the US, almost anything [in the rules] can be bypassed if the state thinks it is important. In the EU, the laws are very tight (in favour of citizens). The UK law is well balanced. We will have to see what works for us,” he said.

FactorDaily had touched upon some of the aspects of international data protection laws in this story: How data brokers track your digital footprint, and profit from it.

Cyberlaw expert Pavan Duggal said the timing of the law is important now that the Supreme Court has signalled privacy will have to be protected in data of the citizens. Still, he said, “The earliest it can happen is the end of the year, other wise it can go to the first half of next year. It’s hard to predict when and at what point of time will a particular legislation come into existence.”

Srikrishna said he expected to start work in earnest on the draft law after he’s back in India September 30. “We (the members of the committee and him) have started exchanging some emails. The outer limit for this exercise is a year. Don’t forget that we will have several meetings with experts, drafts, public consultation…,” he said.

Besides Srikrishna, other members of the committee are: IT and telecom secretary Aruna Sundarajan; Ajay Bhushan Pandey, CEO, UIDAI; Ajay Kumar, additional secretary, IT ministry; Rajat Moona, director, IIT Raipur; National Cybersecurity Coordinator Gulshan Rai; R T Krishnan, director, IIM Indore; Arghya Sengupta, director, research, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy; Rama Vedashree, CEO, Data Security Council of India; and a joint secretary of the IT ministry serves as the member-convener.

In an earlier interview with FactorDaily, tech architect Pramod Varma had touched upon the need for data to be co-owned. “That means, by one’s right to access their own data, these entities should give machine readable data back to users which people can use it to get access to various services,” said Varma.