But Indian researchers and companies working in this field have a big handicap: data. More precisely, the availability of well-labelled, feature-rich local datasets.

The global race in artificial intelligence is like the space race of the 20th century with large powers vying for the pole position. China currently leads the pack with countries such as the US and Israel trailing behind.

India too has big ambitions in this race. The government announced last week that it plans to set up a National Centre for Artificial Intelligence to help citizens benefit from AI and related technologies.

But Indian researchers and companies working in this field have a big handicap: data. More precisely, the availability of well-labelled, feature-rich local datasets, which is one of the biggest hurdles India will have to cross to get ahead in the AI race.

Data is what powers AI and makes it intelligent. Modern AI requires rich datasets and it is stuff that is learned from these datasets that you see working in most AI applications today. These systems need to be trained on local datasets to work for a particular geography or a given set of problems.

“For solving local problems you need locally appropriate datasets. Even if you want to adopt solutions that are being used elsewhere, you want to make sure that they continue to be valid in your context and for that, you also need local data sets,” says Rahul Alex Panicker, chief innovation officer of Mumbai-based AI Wadhwani Institute for Artificial Intelligence. The Institute is also working on creating local datasets across areas for researches and companies in AI.

You might argue that there are vast amounts of data being collected across the country, but the fact is that most of it not useable for AI applications due to the lack of richness and quality.

“There is a lot of digital data available, but a lot of this data has been collected for reporting purposes. Most of this data tracking is done is for programmatic interventions and hence will be very binary in nature and not necessarily feature-rich data. You could do some analytics but not for AI applications,” says Panicker who gives the example of electronic health records. Often, a record will contain very little detail like the patient’s name and the medical problem as a cough and medicine prescribed.

“You’ll find millions of these. What are you supposed to do with these? There are no test results available there. How do you know what type of a cough or any other symptoms? You cannot do any learning on this kind of data,” he adds.”You will often also see the medicine prescribed as ASDF.”

ASDF is the first four letters from the left in the middle row of a QWERTY keyboard, often used as filler text.

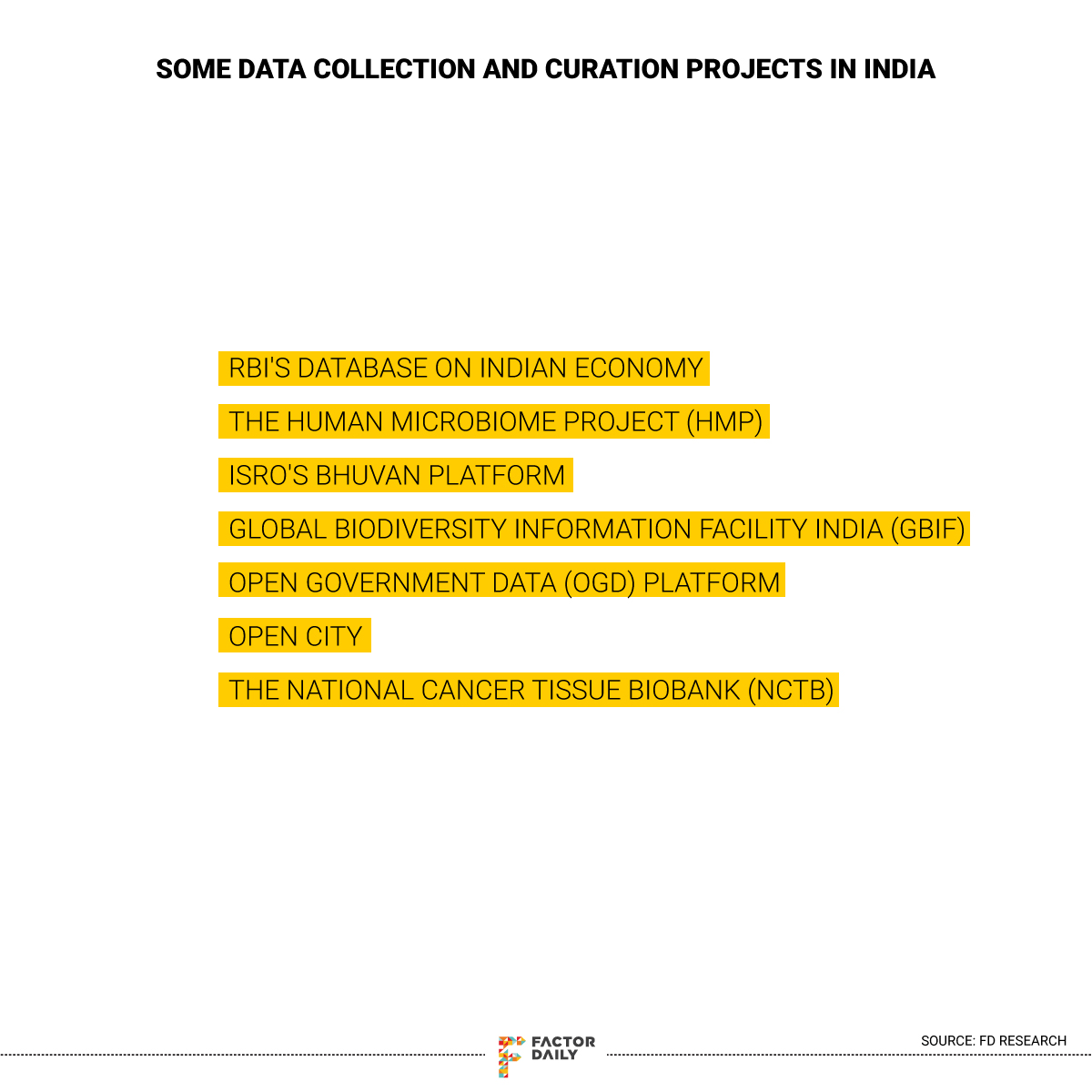

Today there are a few government organisations and apex bodies that make some datasets from India available but they are limited in number and scope. For instance, the RBI maintains a database on the Indian economy, ISRO provides some datasets from its satellites via its mapping service Bhuvan, the Wildlife Institute of India provides some datasets that it tracks and maintains etc. But the reality of the fact is that the sources of datasets are a few and out of them even fewer ones ensure that the data is updated and maintain good data collection practise.

To be fair, the Indian government’s open government data (OGD) platform, started in 2012, does host some data sets, but a 2015 report by research economist Natasha Agarwal for the Web Foundation highlighted some of the key problems with the project, that even plagues the OGD platform today.

“Critical datasets are not available on data.gov.in. Available datasets are often outdated, duplicated, incomplete, inadequately referenced and lack common terms used to describe the data. Top level metadata such as data collection methodology and a description of the variables are also either missing or incomplete. These shortcomings make it difficult to compare and analyse datasets properly,” Agarwal said in the report.

When you look deeper into the data problem, it becomes clearer that the problem is not just about the availability of datasets, but with the specificity of datasets available, the lack of richness in data and data collection practices.

Last year, India’s policy think tank Niti Aayog began working on a plan to build a National Data & Analytics platform. According to Avik Sarkar, head of the Data Analytics Cell at Niti Aayog, the think tank is now developing open data sets from India that are with the various government departments available in the public domain for researchers and companies, especially working in the AI space.

“We are working on making the government data available to the public that can be used for social good,” Sarkar told FactorDaily. “We are also looking at whether private data can also be made available, but that is in very early stages. We have been in talks with corporates and other organisations for this but its still in very early stages.”

According to Sarkar, his department plans to bring previously unavailable large data sets (without personally identifiable information) into the public domain and make them available on an ongoing basis.

For instance, one of the projects Sarkar’s team is working on is to help build a regional language dataset working with All India Radio (AIR).

“For AI, in particular, we are trying to make some datasets available for instance Indian language learning with large datasets from AIR which is not in the public domain now. AIR has a historical repository of news and other broadcast programs in regional languages along with their transcripts which will help with regional language research,” says Sarkar.

Another project the team is working on is in collaboration with Working with Tata Memorial Center (TMC) in Mumbai to develop cancer genomic datasets for researchers in the field.

IIT-Madras has recently set up a National Cancer Tissue Biobank (NCTB) with an aim to help develop an India-specific cancer genome database, according to news reports.

One of the promising Wadhwani AI projects involves collecting data on pests and developing models to be used on the datasets. At the core are sticky pheromone traps that attract and capture insects, pictures of which are taken by farmers and agricultural extension workers on mobile phones. Wadhwani AI’s computer vision system automatically detects, counts the bugs and classifies them. This can be done even when mobile phones are offline with the data syncing up to the database when the device get connectivity.

“Earlier you used to have data on what is happening on your farm but now you have a spatiotemporal map that can tell what is happening in the region and also about what has been happening over a period of time. We can see the progression over time and from this detect pests early,” says Panicker. “Based on this data better advisories can now be given for more precise targeted appropriate intervention to be done.”

The datasets are geotagged and time-stamped potentially reducing human errors in data.

While it may take time for these data sets to become public, innovation in the AI space cannot come to a halt and startups are finding their own workarounds.

Mohali- base agritech startup Agnext has been working on a handful of AI-based applications. Each of the AI models for the various use cases had to be trained on very diverse and different data sets which were initially not easily available in India.

One of the solutions Agnext developed was a spectral analysis device that analyses the curcumin content in a particular turmeric harvest. Curcumin is a bright yellow chemical produced by certain plants and one of the main chemical constituents of turmeric.

Also, see: AI can’t solve farm distress but takes baby steps to improve productivity

“Initially we began working with worldwide crowdsourced datasets and that helped us build the very first model that we ever built. But going forward you cannot build these datasets just on your own, so you have to find a partner with whom you can build,” says Taranjeet Singh Bhamra, CEO and co-founder of AgNext.

At first, the Agnext team also had people on foot collecting data from labs across the country to build these datasets. But today the company has also access to data from its corporate partners, governments, co-operative and apex bodies it works with.

“One of the large agribusiness companies opened their lab for and we build datasets on curcumin along with their team. Instances and partnerships like these help us build a good amount of data sets for training our models,” says Bhamra, whose company developed data sets on various spice compositions through similar partnerships.

Agnext’s team is also working with central and state governments across India on capturing and creating such datasets.

Chennai-based genomic intelligence company Kyvor Genomics is also using AI models to develop its cancer therapy solution called CANLYTx – short for Cancer + Analytics. It is an AI-based system that involves a diagnostic test that identifies patients most likely to be helped or harmed by a new medication and based on that analysis, zeros in on targeted drug therapy.

The company currently does not require local datasets as it is working with internationally available drugs for cancer treatment.

“There are no drugs that have been developed on Indian data. Our focus is currently on therapeutic implications and for that, the drugs are developed based on international data and hence the data we use is also internationally available datasets,” says Abilesh Malli Gunasekar, CEO and founder of Kyvor Genomics.

According to Gunasekar, India specific drugs will surely improve the quality of treatment but until such drugs become available his company is only focused on working with internationally available drugs.

“Indian datasets would help pharmaceutical companies develop Indian specific drugs and only when such drugs become available do we see a need for India specific datasets to train our models,” adds Gunasekar. “We develop our own datasets from patients that come to us, but it is a very slow progression and will take at least two to three years to develop proper datasets.”

Biases in AI is not a new thing. In the West, even ambitious AI projects have been plagued with this problem. Such a possibility in India is very real in the absence of locally and carefully created data, lack of which, for instance, could lead to underrepresented populations. If so, the kind of biases you are likely to see are gender biases and socioeconomic strata biases. You also run the risk of accentuating the digital divide.

Privacy concerns are another problem that isn’t far behind when it comes to data and datasets being used. Private companies and corporate houses in India have a lot of data with them and making it available to the researchers and companies working in the AI domain is one of the tasks NITI Aayog has taken up.

“The moment data collection is involved a negative angle is always brought about and then there is the concern of privacy. Hence, we are treading this path very carefully ensuring all these concerns are addressed before going forward,” says Sarkar.

Panicker of Wadhwani AI feels that tiered access is a possible way to prevent privacy issues. “Tiered access is a good standard wherein what data at which level the access is given. What you publish openly could be completely anonymised but then restricted access could be given to researchers,” says Panicker.

According to Sarkar, there are a few challenges ahead for him and his team, one of them being the ability to access and make available the data from various departments, especially considering the fact that the NITI Aayog, does not own the data. “NITI Aayog might have the intent but a lot of the data is not our own data and that is a challenge,” he says.

Then there is also the problem of data collection which is as crucial as any of the other steps in the process if not more.

Panicker gives the example of a medical screening process for a particular disease. The personnel in-charge go door to door to check for symptoms and the cases that are likely are reported. Unlikely cases are not reported. “For a reporting purpose, that is fine but for learning, you need your negative labels also. For classification, you need the negatives as well as positives. The model won’t know what the characteristics of what normal people are,” he says.

He also points out is the lack of awareness among the data collectors of the importance of such data. “It is more than just educating the data collectors. Educating is nice but it’s actually better if you actually provide utility. If something actually comes out of them giving quality data, then they can see the benefit of this.”