The events and people in this story are all true to life. All the women characters have been assigned fictitious names for two reasons: to respect their privacy and to help readers navigate through a complex narrative of nearly 6,500 words.

Paromita was bemused when she received that call in early June 2016.

The 34-year-old software engineer was working at a client’s location, away from her home in Navi Mumbai. So when an inspector from Hyderabad, K V M Prasad, called her about a case, she didn’t think much of it. He enquired about some online money transfers that she had made to someone named Tanmay Goswamy. She told him she did not know anyone by that name.

Back at home that night, that conversation with Prasad stayed with Paromita. The transaction details – amounts, dates etc. – were familiar.

She checked her old transactions. Whatever Prasad mentioned matched with her transactions. But, she had transferred the money to her fiance: Hemant Gupta.

This puzzled her.

Paromita had met Hemant through Bharatmatrimony, an online matrimony portal. It was December 2013. Soon after she created her profile, Hemant had contacted her. He found her phone number from her profile and called her.

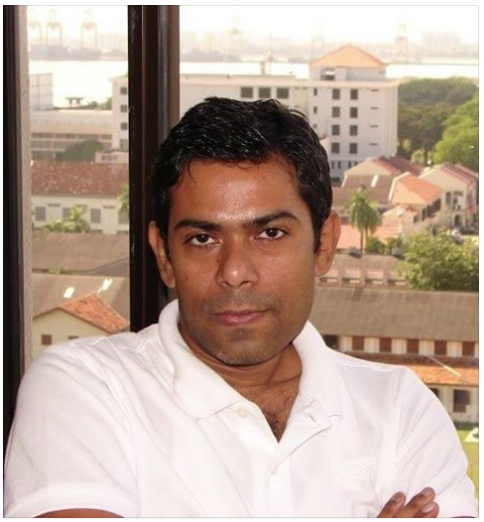

Paromita checked his profile and she was impressed. He was an officer of the Indian Revenue Service (IRS) posted in Bengaluru. He came from a wealthy and educated family. His mother was a doctor while his father was an officer of the Indian Administrative Service working in the Union home ministry.

Hemant started calling Paromita often. “In fact, he was chasing me,” she recalls.

They chatted with each other for a couple of months. Then, he came to Mumbai to meet her.

He was a charmer, she says. “He had a knack for figuring out what a girl would be interested in talking about. And he certainly knew the trick to impress a girl. He paid me attention and told me a lot of stories,” she adds.

They started meeting often. He would talk about his job and his family. Though she never met his family, he often spoke about them. He talked about many of his cousins, where they lived and what they did. He would share details of his work and showed her a website, where he logged on using his ID and password. He showed her a page. It displayed his rank and designation in the IRS, along with his residential address.

He spoke about how wonderful their life together was going to be. “He treated me really well. He spoke about the future. All the good things that were going to happen and all the plans he had for us,” she recalls.

“He gave me hope, a lot of hope.”

In 2014, they had a setback. Hemant told Paromita that he was suspended from his job. At the time he worked as the Deputy Commissioner of the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) and was posted in Bengaluru. “He told me ‘I and a couple of friends got suspended from our jobs. I have always done the right thing. But some criminals backed by politicians are harassing and chasing me’,” Paromita remembers him saying.

Hemant gave his documents – passport, voter ID, and driver’s licence – to Paromita for safekeeping.

“He told me he needed money to get his job back. I helped him with a lot of money to see through this time,” she says.

Hemant got his job back and they were planning to marry him in a couple of months when Inspector Prasad’s call came.

The call left Paromita confused. She thought the police were mistaken. Once she returned to Mumbai, she called Hemant. It was late in the night on June 8, 2016. His phone was switched off. “It was unlike him. He had never switched off his phone in the three years I had known him. Never. I was tense,” she says.

Clueless, she Googled Tanmay Goswamy. A Facebook post from the Hyderabad cyber crime police turned up. The post detailed how a man defrauded a woman of several lakhs of rupees after meeting through a matrimony website. The post also had a picture of the man.

“It was him. It was Hemant Gupta,” says Paromita. She sounds more dejected, less angry. She doesn’t sound particularly emotional since she has gone through this moment in her head several times since that day.

From the news reports that followed, she gathered that he was married with a child when he met her. That Hemant wasn’t his real name. His name was Tanmay Goswamy.

“I went numb. I don’t remember what happened or how I felt. I came back to my senses only when my maid knocked at the door in the morning,” she says.

According to the police, Goswamy defrauded Paromita of Rs 35 lakh.

There is no single estimate of the scale of online matrimonial frauds in India but it is big. More than 200 such cases, with a total loss of Rs 5 crore, have been reported in the past three years in Bengaluru, the Times of India newspaper reported in April last year. Pune City Police received 62 complaints of online matrimony frauds (cheating of a total of Rs 3.75 crore) in 2016 while 2017 has seen 54 cases in just the first six months.

“From what I have seen, seven out of 10 profiles on matrimony websites are fake,” says Puneet Bhasin, a lawyer practising in Mumbai in litigation matters involving cyber crimes.

******

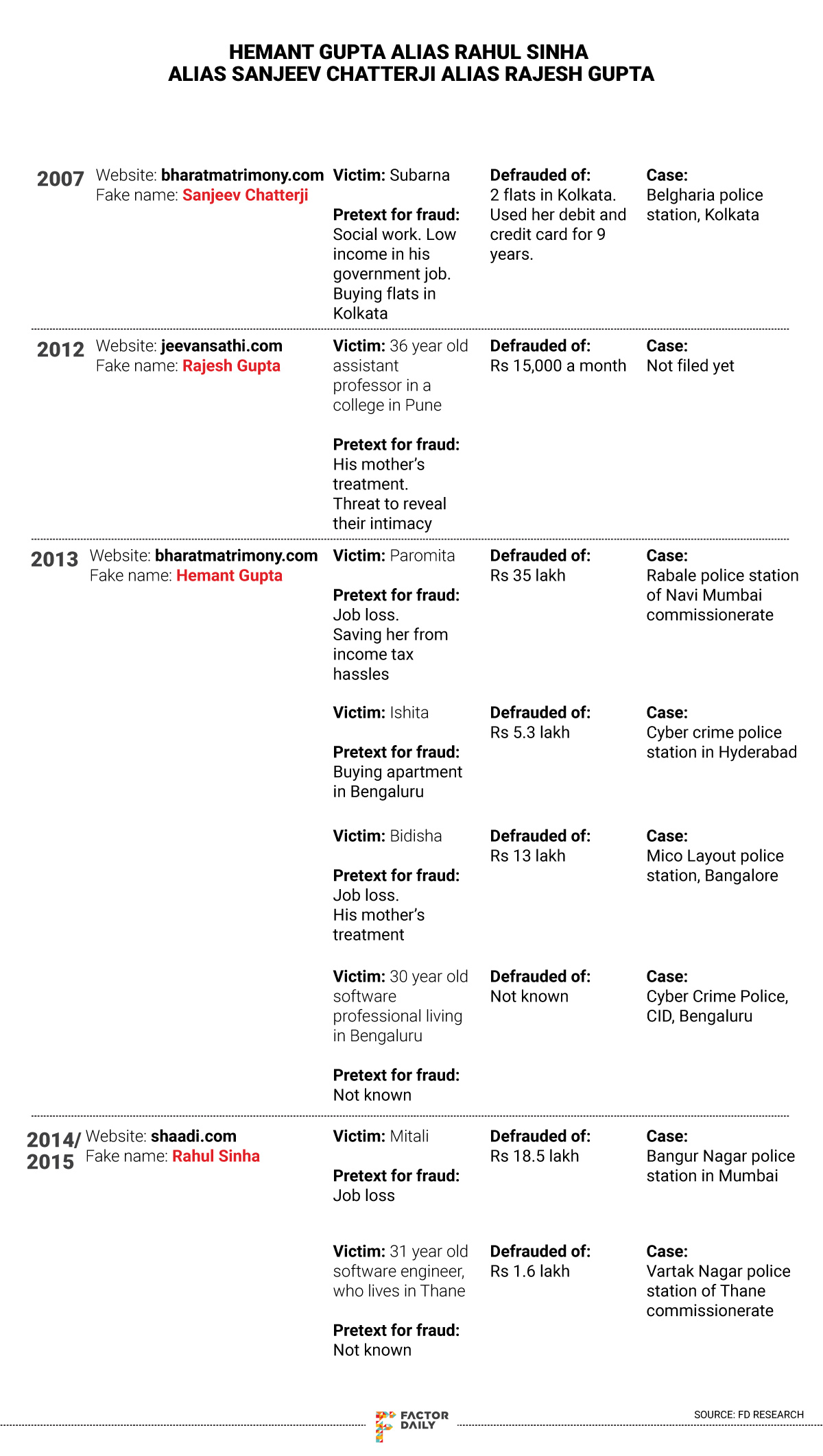

Currently, seven cases of matrimonial fraud are on against Goswamy: three cases in Maharashtra (Mumbai, Navi Mumbai and Thane), two in Bengaluru, and one each in Hyderabad and Kolkata. Another victim in Pune has not filed a case. The police estimate that he has swindled them of at least Rs 1.25 crore. They suspect many other victims have not come forward to file complaints — one estimate put at 30 the number of women he duped.

Goswamy chose his victims carefully: Bengali women, in their 30s, financially independent, and living away from their families.

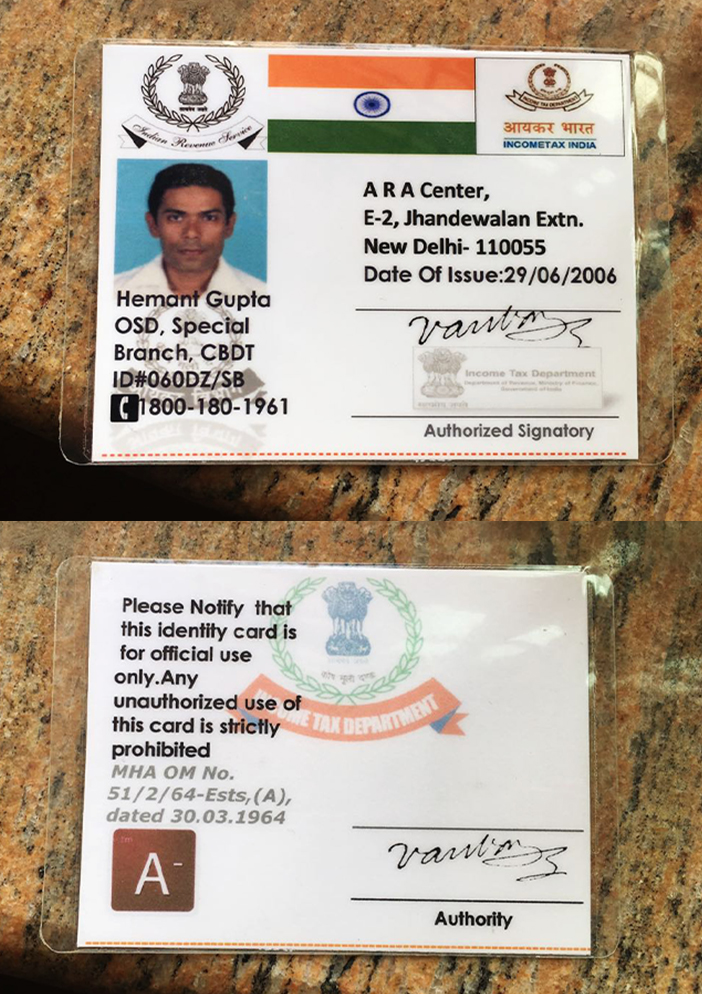

His strategy with the women was similar: He posed as an IRS officer who worked undercover. This helped him explain away tricky situations like why an office wouldn’t acknowledge his employment, why he needed to keep his identity secret, why he carried an identity card in another name, or why he couldn’t make money transfers from his bank account.

His stories in swindling victims were also similar: he lost his job and needed to get it back or start a business. Or, down payment on a house for a post-married life.

The elaborate fraud unspooled towards the end of 2015. Ishita, 39 years old and a hotel industry professional, had lodged an FIR with the Hyderabad cyber crime police against him.

With Ishita, he employed the same tactics that he used with Paromita. Three months before he introduced himself to Paromita, in September 2013, using his alias Hemant Gupta, he contacted Ishita through – again – Bharatmatrimony. Goswamy told her, too, that he was a Deputy Commissioner of CBDT in Bengaluru. He sent her pictures of him and they would do video calls regularly.

“I asked a friend to do a background check on Hemant. He got back saying everything was fine and I trusted him,” says Ishita.

Things were going well and they decided to get married. Goswamy spoke to Ishita about settling down in Bengaluru after their wedding. He talked about buying an apartment in her name. He said he would pay the EMI but needed her help to pay the booking amount.

To make the booking, Hemant asked her to transfer the money to Tanmay Goswamy. He told her that Goswamy was the legal head of the property developer. So, Ishita made an online transfer of Rs 5.3 lakh in three instalments to Goswamy’s account.

When she started enquiring about the property documents, Hemant began to make excuses. She asked him to return the money, which he said wasn’t possible due to a lock-in period of one year. She never got back the money.

This was when Ishita had a hunch that there was something wrong. She also grew suspicious of the elaborate stories Hemant told her about his job. “Pretty honestly, I had ignored many clues. I was afraid I was being too picky or suspicious,” she says.

“But, when somebody goes out of his way to portray himself in a particular way, it gives you a feeling that it may not be true. That it might be completely false.”

She stopped meeting Hemant. When he made repeated attempts to meet her, she asked him to speak to her mother and fix a date for their wedding. After this, he started avoiding her. Soon, his phones were switched off.

Ishita made a few enquiries. She enquired about his residential address and it turned out to be fake. Next, she called up the office where he was posted at. They told her no such person worked at that office.

In the course of their relationship, Goswamy had often spoken to Ishita about the secret nature of his job in the CBDT. He had told her it was crucial his job was undercover and his identity a secret.

“I thought the office actually didn’t want to disclose his identity. I did consider that. Or, maybe he was transferred. I gave him the benefit of the doubt for some time,” she says.

But, the more she deliberated on this, the surer she became about his fraud. She still wasn’t sure whether she wanted to complain to the police. “He had portrayed himself as a government official and I worried a complaint against him would backfire. I did dilly-dally on this for a while, thinking whether to take the step or stay quiet,” she says.

“Then I realised if I don’t do this, such people get a leeway. It encourages them to do this to more people.”

On November 27, 2015, she registered an FIR with the Hyderabad cyber crime police. The case was filed under Section 66 (C) and (D) of the Information Technology Act, 2008. These deal with identity theft and cheating by personation using a computer device. Charges were also filed under Section 420 of the Indian Penal Code, which deals with cheating.

This is when Inspector Prasad took up the investigation. The phone numbers available with Ishita were of no use. Hemant had stopped using them and the numbers had been allotted to other users. Prasad decided to look for clues in the bank transfer to Tanmay Goswamy.

He observed another transfer of Rs 10 lakh earlier that year into Goswamy’s account. This was the transaction that led him to Paromita. Then, Prasad checked Paromita’s bank statements and noticed she had made one more transfer of Rs 10.2 lakh into another account. This turned out to be Goswamy’s wife’s account. Paromita’s bank statement also showed she often recharged Hemant Gupta’s phones and paid his bills online.

Prasad became certain there was a connection between Hemant and Tanmay.

From the bank details, Prasad traced and reached Tanmay Goswamy’s address in Kolkata on May 30, 2016. He had Hemant’s photos that he got from Ishita. In Kolkata, he got Tanmay’s photos from his bank documents.

“It was the same person in the two photos. The person who asked Ishita to transfer the money and the one who received it in his account. Hemant Gupta and Tanmay Goswamy were one and the same,” says Prasad.

Prasad pieced together some of Goswamy’s life in Kolkata. He found that he married a teacher working at a government school in Kolkata. They had a 10-year-old son. His father Raj Behari Goswamy, a state government clerk, was no more. His mother had retired as an attender in a local court and lived in the same building as his wife and child. Goswamy had remained jobless after graduation.

Prasad couldn’t find Goswamy or meet any of his family members. “I was surprised to see two security guards outside his house. His wife refused to open the door and the local police refused my request to break it open. But, I gathered that he had last visited his house in January 2016 and was currently in Mumbai. I also got two of his current phone numbers,” he says.

Prasad boarded a train to Mumbai. Using his current phone numbers and cell phone tower records, Prasad pinpointed his location to an apartment complex in Malad West, Mumbai.

On June 6, 2016, he went to the apartment and enquired with a security guard with Goswamy’s photo. The guard confirmed that the person lived there but wasn’t around at the moment. Prasad waited there all day and night.

Meanwhile, he had received the help of the local police. Finally, early next morning, Prasad spotted Goswamy entering the apartment. He apprehended and questioned him.

“Which floor do you live on?”

“The 5th floor.”

“Let’s go to 5th floor. Who do you live here with?”

“I live with my wife. But she is not home right now.

“Call her. Ask her to come here.”

The woman, Mitali, arrived soon. Prasad told her how Goswamy had cheated Ishita in Hyderabad. She didn’t believe him. She told him she was married to the accused and his name was Rahul Sinha.

Mitali, a 34-year-old art director in the film industry, had met Goswamy in May 2015. This time, he met her on Shaadi.com using the name Rahul Sinha. Rahul had mentioned in his profile that he was an IRS officer, his father an IAS officer and his mother a magistrate. He said he was based in Bengaluru but often visited Mumbai for work.

They chatted and met often. In a few months, they married at the Siddhivinayak temple in Mumbai. She fondly called him Sonu. Over the months, Mitali gave him Rs 18 lakh when he told her that he lost his job. The reasons were the same — a conspiracy hatched by his colleagues. They had been living in her Malad flat for six months when Prasad landed there.

Prasad recalls: “I questioned Goswamy who’s Hemant Gupta. He confessed, ‘It is my fake name’.”

Mitali was baffled as Inspector Prasad told her the story of a Goswamy victim. “She collapsed on the floor. She did not speak a word for an hour. It took her a while before she could gather herself and stand up. I felt terrible seeing her in that condition,” recalls Prasad.

******

Paromita realised she had been conned only after she Googled Tanmay Goswamy and read the details of his frauds.

“My life suddenly turned upside down. The last three years came to me in a flash. I couldn’t figure out one thing that he didn’t lie about. I was living in a web of lies,” she says.

Her family was distraught but less shocked. Her parents had their doubts about Hemant. Over the years, they had tried to contact his mother many times. But, he had some excuse always. Whenever Paromita’s father spoke about visiting his house in Kolkata, Hemant made up excuses. “My parents found all this suspicious. But I never paid any attention to it,” says Paromita.

His arrest made her think about how often he asked her for monetary help. It began with small amounts such as mobile recharges. It grew bigger and bigger on various pretexts, including job loss. She estimated that she helped him with over Rs 12 lakh to fix problems related to his job.

But Goswamy’s most elaborate con with Paromita related to some tax advice he gave her.

Paromita’s father had purchased a house in Kolkata. Hemant told them the papers related to the house weren’t in order and they would face an income tax raid. He advised her father to get a loan of Rs 20 lakh and send the money to Paromita. She who would then transfer the money to Tanmay Goswamy, a Kolkata based advocate.

He assured them when the money is transferred through these accounts, their income tax problems would be over. Goswamy would return the money to Paromita once the issue was settled.

Paromita followed Hemant’s instruction. She transferred Rs 10 lakh to Tanmay Goswamy and another Rs 10.2 lakh to his wife. Both names were unknown to her, but she did it on Hemant’s advice.

On report of his arrest by Hyderabad police, her parents advised her to approach the police and lodge a complaint. Paromita met many girls, who Goswamy had swindled. “He had told them all stories very similar to what he told me. The names, jobs and residences of these girls were what he passed off to me as details about his cousins,” she says.

She was sure about filing a case but had to wait several days before the police were convinced. This was despite the fact that Goswamy had already been arrested by the Hyderabad police in Ishita’s case.

“I knew Hemant Gupta, but it was a fake name. All the details I knew like job and residential addresses were fake. What I was talking about was a massive forgery and the police were not sure about it. It took a call from a high-ranking police official in Hyderabad to the Commissioner of Police in Navi Mumbai for my FIR to be registered,” she says.

There was something that complicated her case even further. Just before Goswamy was arrested, he had driven down from Mumbai airport to the Malad apartment. The Ford Figo he was driving was Paromita’s.

According to the police, Goswamy had pressured her into buying it for his use. He offered to pay the EMIs. He later asked her to transfer the ownership of the car in somebody else’s name, which Paromita refused. Later, Mitali told the police that he had promised her that car as her birthday gift. He had told her it was his relative’s car and he would buy it for her.

“My car was seized by the police, who assumed the owner of the car was an accomplice in his crimes. I had a hard time trying to establish that I was not a criminal but a victim,” says Paromita.

The police blamed her and asked her how she could be so foolish despite her good education. She recounts how the comments on news reports about Goswamy’s case were negative, with readers calling the victims “foolish”, “greedy” and “desperate”.

Even the response of matrimony website was disheartening. Ishita is disappointed with the way the website handled her complaint. “Bharatmatrimony took no action. They didn’t even respond to my calls and emails; not even an apology,” she says.

“We suspend the (fake) profile. We encourage the aggrieved person to file a police complaint and we support the investigation by providing details. When we are requested by a competent authority, we provide the alleged defrauder’s details to them,” said Murugavel Janakiraman, founder and CEO of Matrimony.com, parent company of Bharatmatrimony

******

During the course of investigation, the Hyderabad police unearthed more cases involving Goswamy.

Prasad found debit and credit cards of some women in his wallet, including Subarna’s. A few high-value transactions had already led him to probable victims like Paromita. Many came forward with their stories. Another source of clues was Goswamy’s profiles on matrimonial websites. Using these, the police were able to piece together his operation in detail.

Matrimonial sites were key to his operation. Through these sites, Goswamy was able to cast his net far and wide across the country. Something that would not have been possible 15 to 20 years ago, when the internet wasn’t so accessible.

On Bharatmatrimony alone, he sent requests to 300-400 women, and spoke to several at the same time, according to the chargesheet filed by the Hyderabad cyber police. After some time, he would delete his profiles from matrimonial sites to wipe any evidence and create new ones. This was crucial for him in changing his identity and avoid being noticed by the women he was already in touch with.

After cheating Subarna through a profile on Bharatmatrimony in 2007, Goswamy created a fake profile on Jeevansathi in the name of Rajesh Gupta in 2012. Through this, he contacted a 36-year-old assistant professor in a college in Pune. He promised to marry her and began borrowing money on the pretext of his mother’s treatment. After a couple of years, she lost hope of marriage but was afraid of him revealing their relationship. She gave him her debit card on the condition that he would not use more than Rs 15,000 a month.

After cheating Subarna through a profile on Bharatmatrimony in 2007, Goswamy created a fake profile on Jeevansathi in the name of Rajesh Gupta in 2012. Through this, he contacted a 36-year-old assistant professor in a college in Pune. He promised to marry her and began borrowing money on the pretext of his mother’s treatment. After a couple of years, she lost hope of marriage but was afraid of him revealing their relationship. She gave him her debit card on the condition that he would not use more than Rs 15,000 a month.

The same year, he created another profile on Jeevansathi in the name of Hemant Gupta. Through this account, he defrauded Bidisha, who works in the research wing of an MNC in Bengaluru, of Rs 12-13 lakh.

In 2013, he deleted his Jeevansathi profiles and created another profile in Hemant Gupta’s name on Bharatmatrimony. It was through this profile that he met Paromita and Ishita. Through this, he also met a 30-year-old software professional in Bengaluru. But, after she found the identity card of Tanmay Goswamy with the photo of Hemant Gupta in his wallet, she broke all ties with him. She realised the magnitude of his scam only after his arrest and lodged a complaint with Cyber Crime Police, CID, Bengaluru. When Inspector Prasad contacted her regarding Goswamy’s case, she had found closure with Hemant, had married, and was pregnant with her first child. “Despite some pregnancy-related health issues, she didn’t hesitate for a moment to come forward and lodge a case against Goswamy. She helped us with the details too. It was great to see that her husband was very supportive of her,” says Prasad. “She is a very brave lady.”

Goswamy also created another profile on Shaadi.com in the name of Rahul Sinha, through which he met Mitali. Through the same profile, he also met a 31-year-old software engineer in Thane, who he had duped Rs 1.6 lakh of. He avoided her after she got suspicious and started questioning him.

He used several aliases – Hemant Gupta, Sanjeev Chatterji, Rajesh Gupta, and Rahul Sinha – to support his elaborate con. He would use fake ID cards to gain the trust of his victims and even give it to them — for safekeeping, he said. To Paromita, he gave his passport, voter ID, and driver’s licence identifying him as Hemant Gupta. To Bidisha, he gave a voter ID and employment ID card in Hemant Gupta’s name. And to Subarna, he gave an employment ID card that had him as Sanjeev Chatterji.

Goswamy also used multiple SIM cards to keep women off his trail. He discarded the SIM cards and phones to wipe out evidence. The police had a tough time tracing his location based on his calls (from cell phone tower records) as he kept changing SIM cards. Before getting arrested, he had changed over 15 SIM cards in four years.

Goswamy’s windfall from his cons was significant. The chargesheet in Hyderabad case mentions that he spent a lot of the money extracted from the victims on high-class sex workers. He also bought two cars: a Nissan Sunny and a Tata Safari.

FactorDaily reviewed the chargesheet filed by the Hyderabad police in Ishita’s case. It mentions that Goswamy “confessed to cheating eight women and looted money from them”. The chargesheet states that Goswamy has committed offences under Section 66(D) of the IT Act, 2008. He was also charged under Section 419, 420, 468, 471, 494, 201 and 120(B) of IPC.

A person close to Goswamy says the case against him has roots in a business rivalry. “Goswamy’s former business partners in Kolkata had a fallout with him,” said the person, asking to stay anonymous. And, the women? “It is a misunderstanding on their part.”

******

On a Saturday morning in mid-December, Bidisha appears for her hearing at the VI Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate (CMM) Court in Bengaluru. She’s waiting to take the stand to undergo cross-examination by the defence lawyer.

Bidisha is in her mid-thirties and has been working in Bengaluru for the last few years. Her story – that of a single woman in her mid-thirties, hailing from a small village in Bengal, with a promising professional career in a global conglomerate accompanied by financial independence – is the kind that’s celebrated in new India.

Bidisha completed her post graduation in Kolkata and moved to Hyderabad for a job. She then jumped to a bigger position in the research division of an MNC in Bengaluru.

In court, she blends in among the plethora of petitioners and victims, all waiting for the wheels of justice to roll. Her glasses give the impression of someone who pores over reams of technical data in her job.

When FactorDaily asked about her case, she was reluctant to talk about it. She smiles politely, in a self-conscious way. But after verifying our credentials, she opens up a bit.

“It’s hard to trust anyone after all this,” she says with a sigh. “And it’s still too painful to talk about this.”

When Goswamy met Bidisha’s parents in October 2014, they grew suspicious as he was non-committal on a wedding date. “I defended him,” she says, with a sigh. “I explained to them that we would get married once his new venture was running well.”