Farzana finally got through to her mother after three months. It was August 2017, and she was calling from a tiny room on GB Road in Delhi — one of India’s largest red-light districts. A regular client let her use his phone. Farzana didn’t want to tell her mother the truth of her situation. Instead, she told her that she was in Mumbai. That she was doing well.

(The real names of Farzana and the other victims of sex trafficking have not been used in this story to protect their identities.)

A few months before, in a tiny village in West Bengal’s South 24 Parganas district, Farzana was preparing for her matriculation exam. She was the fourth of five children. With her father out of a job, the family survived on the earnings of her elder brother who drove an auto rickshaw. Life was hard but Farzana, unlike her siblings, had gotten a chance to study.

In April 2017, Farzana received a call on her phone from an unknown number. A soft-spoken boy spoke. He told her his name was Sabir Ahmad Gazi and that he got her number from his brother. Farzana hung up. Sabir called Farzana again the next day. And the day after. And the day after that. Until she became less reluctant to speak with him. She started having long conversations with Sabir. They spoke about life and dreams; they spoke about love.

Soon, Sabir proposed marriage to Farzana. He promised her a good life and offered to take her to a big city — Delhi. They planned to elope. It didn’t matter to Farzana that she had not met Sabir in person or that they knew each other only over the phone. She was 16 and in love.

On May 17, 2017, within a month of that first call, Farzana left her house to be with Sabir. From Diamond Harbour, they took a train to Sealdah in Kolkata and then another train to Delhi. What happened next was not how Farzana had imagined it.

Sabir took Farzana to Loni in Ghaziabad – part of the National Capital Region around Delhi – and introduced her to Muniya, who, he said, was his sister. He also introduced her to Muniya’s sons, Vinit and Sonu. Sabir asked Muniya to teach ‘the work’ to Farzana. “What type of work?” Farzana asked. Sabir responded with a slap. He spent the night there and disappeared in the morning.

Muniya, with two other women, Manju and Riya, started Farzana’s ‘training’. They forced her to speak in Hindi, a language unfamiliar to her. They often fed her just once a day. They made her swallow a tablet every day; she doesn’t know what it was for. Sonu would mercilessly beat her. Vinit raped her several times.

After a month, Manju and Riya took Farzana to GB Road in Delhi and handed her over to Bhanu, the head of Kotha number 56. At the brothel, Farzana would begin work at 10 am. She would have her first meal of the day only after the shift ended at 4 pm. The meal depended on feedback from the day’s customers. If someone complained, Bhanu would starve her. On good days, she ate roti, dal and sabzi. The evening shift was from 8 pm to 4.30 am. Dinner was served after. Over the two shifts, between 20 and 25 men would be forced on Farzana.

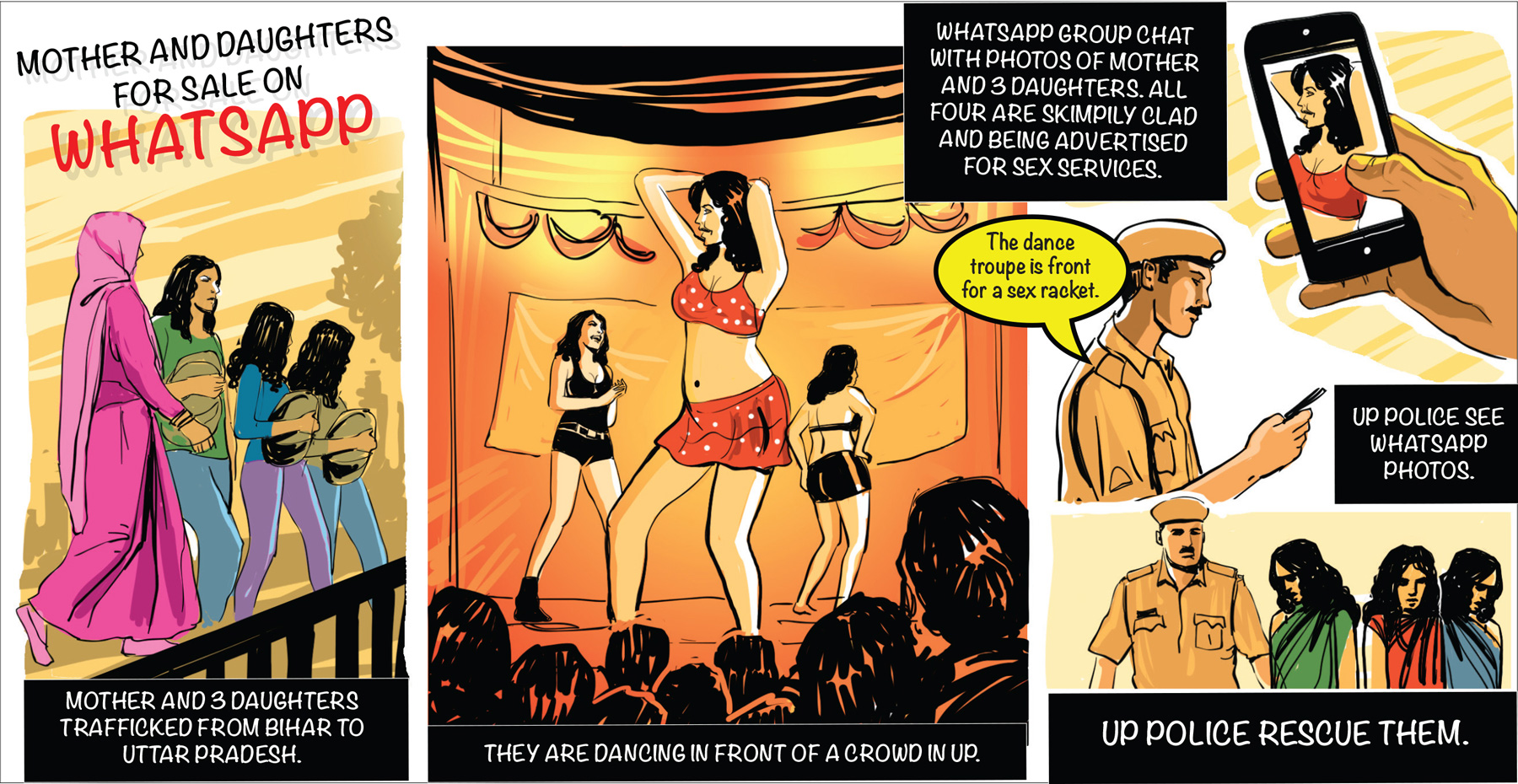

Sabir had lured Farzana into a sex trafficking network simply by calling her by phone, without ever meeting her in person. In Jharkhand, a trafficker trapped another 16-year-old girl using WhatsApp.

The daughter of a daily wage labourer in the coal mines of Jharkhand’s Ramgarh district, Neetu received a WhatsApp message one day in 2016. Like Farzana, she didn’t know the boy who messaged her but he soon managed to get her interested. They began chatting regularly and soon the boy proposed marriage. When she said her parents wouldn’t agree, he asked her to come to Delhi. Unbeknownst to her, he had already fixed a deal to sell her into sex work for Rs 1.5 lakh.

This entire trafficking act was pulled off solely through WhatsApp, says Baidyanath Kumar, an anti-trafficking activist and a member of Jharkhand’s Child Welfare Committee (CWC), a statutory body. “I was shocked at how efficiently the trafficker used social media to traffick a girl out of her house just by typing on his phone and without even having to step out himself.”

Neetu’s parents approached the police. The anti-trafficking squad of Jharkhand police got involved and, with the help of Delhi police, rescued Neetu. In the same operation, five other girls were also rescued — two from Jharkhand and three from Bihar.

All the six girls were trafficked after establishing contact through WhatsApp.

Neetu’s and Farzana’s cases show how networked technologies – mobile phones, the internet, social media, the darknet, and even cryptocurrencies – have exacerbated the grave problem of sex trafficking in India. The trust-building phase of the recruitment process is increasingly being done online, often by young boys.

What distinguishes such technology-enabled trafficking is the lack of a need for in-person contact. By this definition, over half of the trafficking cases in the country would qualify as tech-enabled, says Siddhartha Sarkar, a working group member in the social justice and empowerment division of NITI Aayog, the government’s policy think-tank. “If you’re talking about a trafficker exploiting technology at any stage of his business, then almost all trafficking cases will fall in that category.”

Mahesh Bhagwat, commissioner, Rachakonda Police, in Telangana, says he has witnessed quite a few tech-enabled trafficking cases in recent years. “Just do a Google search about Rachakonda sex trafficking cases and you will find several in the last two-three years that have a social media angle or have used a website,” says Bhagwat, whom the US Department of State honoured in its Trafficking in Persons Report in 2017 for his “remarkable commitment to the fight against human trafficking for the last 13 years”.

Even so, Bhagwat adds, “I wouldn’t say the percentage is huge. But it’s increasing for sure.”

Several others also committed to the fight insist the magnitude of the problem is huge. But it’s easy to see why Bhagwat thinks otherwise.

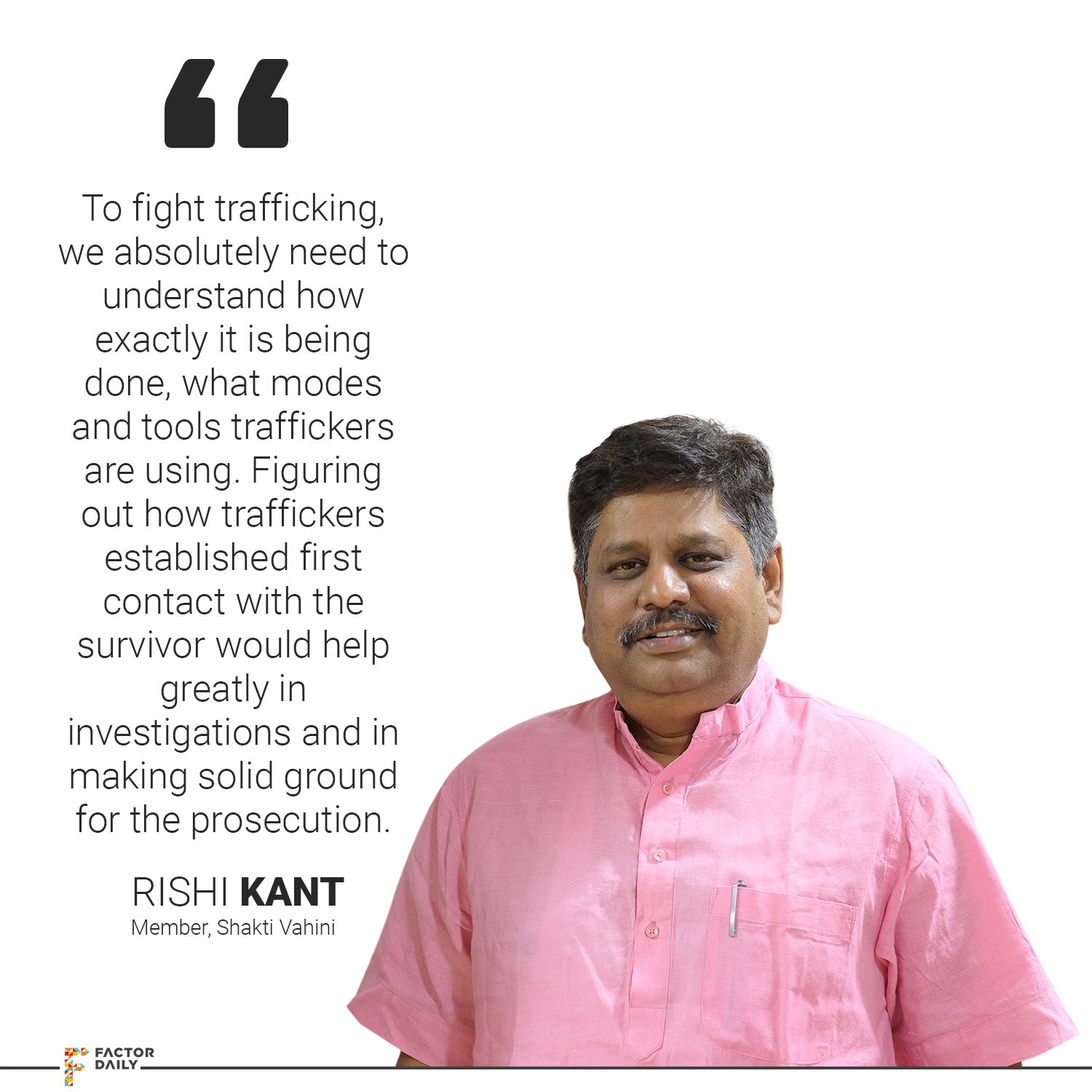

“Tech-enabled trafficking is far more common than most people believe,” says Rishi Kant, a member of the Shakti Vahini, a non-governmental organisation (NGO, or nonprofit) that was involved in Farzana’s case. “When a girl is trafficked, people ask what happened after she was trafficked. How many times has the system tried to find out how exactly the trafficking was carried out? This is partly why, to some, the number of tech-enabled cases doesn’t seem as huge as it actually is.”

To understand how big a problem tech-enabled trafficking has become, FactorDaily got in touch with at least a dozen police officers and over 20 NGOs fighting trafficking in Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Delhi, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Meghalaya, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. The accounts of Farzana, Neetu and other victims have been reconstructed from extensive interviews with the police, NGOs and others involved in their cases.

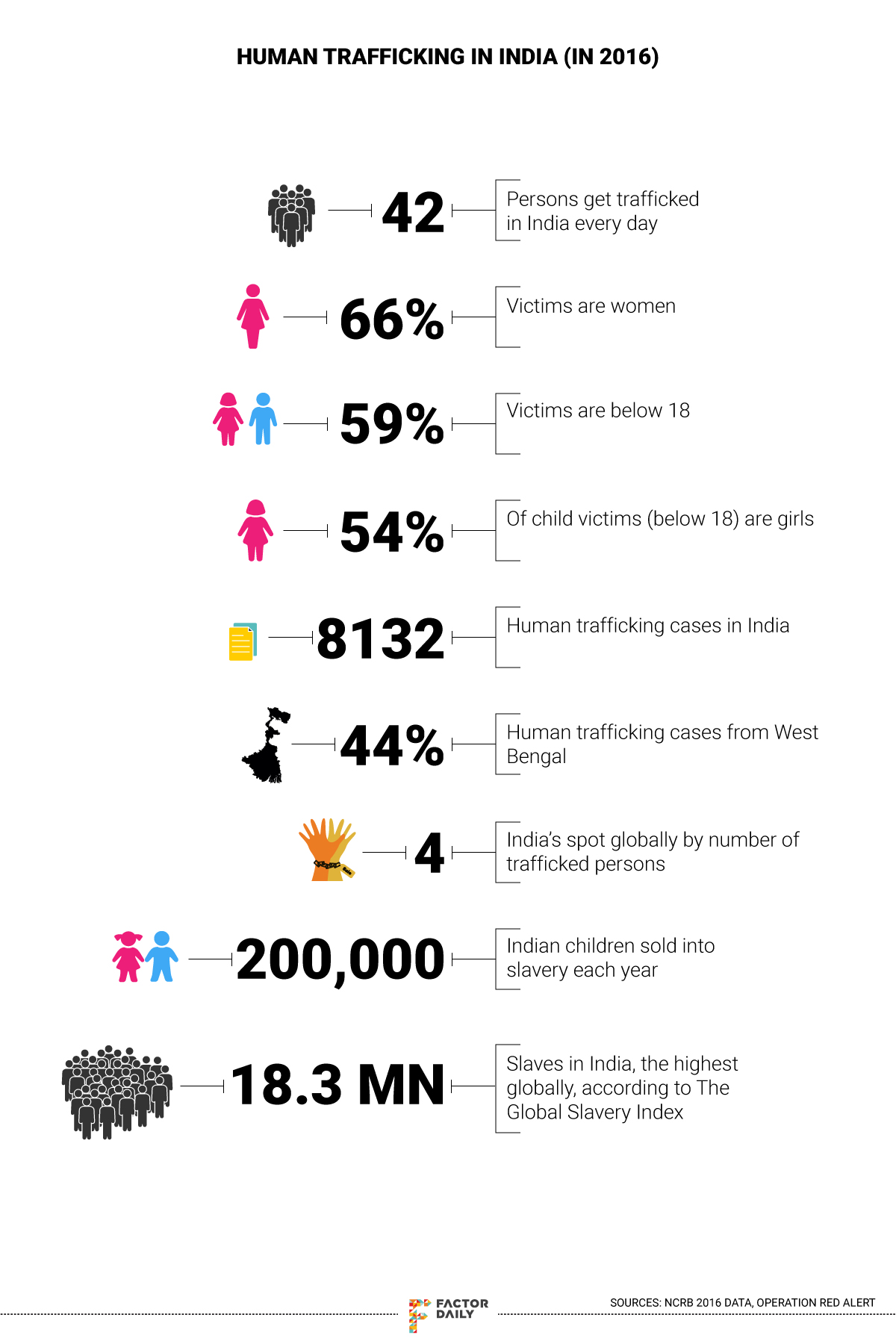

Everybody said tech-enabled sex trafficking cases were increasing, and cited several cases reported from across India. However, we only have anecdotes. No organisation has data or conducted empirical research on tech-enabled trafficking. (Even for overall human and sex trafficking cases, the latest available data is for 2016.) Police and caseworkers don’t always identify these as trafficking through digital tools. Nobody is categorising these cases as a specific phenomenon — a new modus operandi of trafficking based on virtual connections.

“Unfortunately, there has been very little research done on the prevalence of trafficking enabled through social media,” says Phil Bennett, a board member at Destiny Foundation, a Kolkata-based NGO combating sex trafficking. “It would be wrong to extrapolate from a small dataset without careful research. However, we can say that the problem is growing in India and it is becoming more urgent to tackle the issue.”

There, however, exists one reference work in this area.

Between 2010 and 2013, Sarkar, then a researcher attached with universities in Thailand, Hungary and the United Kingdom, conducted face-to-face interviews with 97 women victims, 64 traffickers, and 85 clients across India, Nepal, Thailand, Hungary and the UK to understand the role of technology in sex trafficking. The surveys included nearly 100 participants from India, mostly from Assam, Bihar and West Bengal, the state with the highest number of human trafficking cases in India.

Sarkar’s field survey, published in 2015, showed that traffickers widely used sophisticated software to safeguard their anonymity, online storage and hosting services, and advanced encryption techniques to evade the police.

In the absence of current research on tech-facilitated trafficking, interventions and policies can only be shaped by speculation or extrapolation from a few publicised cases.

“To fight trafficking, we absolutely need to understand how exactly trafficking is being done; what modes and tools traffickers are using,” says Kant. “Figuring out how traffickers established first contact with the survivor would help greatly in investigations and in making solid ground for the prosecution.”

To bridge some of this knowledge gap, Sarkar, along with researchers from several other countries, is working on a book on technology-facilitated trafficking in seven countries. “This book will provide a lot of India-specific perspective, all based on primary data from hundreds of interviews,” he says.

Despite the data uncertainty, anti-trafficking agencies are developing a decent understanding of the tools and platforms exploited by traffickers.

In most cases, traffickers source the phone numbers of girls from stores selling mobile phone call and data recharge packs in villages, says Tathagata Basu, superintendent of police, Sundarban police district, a source region for many trafficking cases, in West Bengal. “When a girl recharges her phone, he notes down her number. He passes it on to the trafficker, who initiates contact by calling the girl or texting her.”

Though a lot of luring is done in the form of marriage proposals, traffickers are finding traps beyond this. They peddle the idea of well-paying jobs in big cities. Auditions for modelling and reality TV shows are also being increasingly used as a front, says an activist who has worked on several cases of tech-enabled trafficking. She declined to be identified.

Traffickers also advertise for mass reach and lure young boys and girls into calling them. Globally, websites (including social media websites) hosting advertisements for exploitative jobs are becoming more common and are being used by traffickers to facilitate international trafficking, says Bennett of Destiny NGO.

Several websites carry ads that promise easy money with claims like “Earn Rs50,000 a month sitting at home”. This is the online version of ‘Mujhse Dosti Karoge’ (will you be my friend) ads in the newspapers, says Kumar of the Jharkhand CWC.

“The phone numbers that these ads carry are (usually) of trafficking groups. Some small-town girls, usually teenagers, call these numbers out of curiosity or desperation for a better future. The person on the other end sweet talks her into his trap. We recently rescued a girl who called one such number for a job but was trafficked to Bihar and pushed into sex work,” says Kumar.

In 2017, Delhi Police came across advertisements on social media by a trafficking racket that provided girls on demand, some as young as 14. The girls were trafficked from several states.

Locanto.net, a website for free classifieds, is particularly notorious for such advertisements, says Bhagwat of Rachakonda Police. “They are advertising girls by age, height, area, etc. They have minors as well as foreigners. These ads carry phone numbers on which a deal can be made. We often decoy them by calling these numbers, asking them to meet us and then arresting the traffickers and rescuing the victims.”

In these ads, distinctions between trafficking victims and voluntary sex workers are blurred. Bhagwat says many of the girls, including adults, in online ads are victims of trafficking. “Most of them are trafficked as minors and pushed into sex work. They are forced to continue it even after they are adults.”

In rural India, a boy chasing after a young girl or a boy and a girl talking with each other draw a lot of public attention. WhatsApp is changing that. But this means traffickers, too, can use WhatsApp for unprecedented direct access to young girls. “He is in touch with the girl without being seen by anybody. Through texts, he is constantly getting updates on her schedule, the places she frequents, her family members, etc.,” says Kant of Shakti Vahini.

Another advantage of online recruitment is that perpetrators can spam several girls from different locations at once, often with the same message of proclamation of love or a job offer.

WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption makes it a perfect platform for such communications. Technologies using encryption that ensure our safety and privacy on the internet are being used perversely by traffickers, says Bennett. The Facebook-owned messaging platform – the largest in India with more than 200 million users – is under pressure from the government to allow access to encrypted messages but is resisting.

Facebook, too, is highly preferred since it presents a lot of personal information to the trafficker. Generally, traffickers target vulnerable populations through coercion, blackmail, abduction, etc. A platform like Facebook makes it easier for them to identify potential victims. Besides profile photos, check-ins, and details of a person’s likes and interests are available. These help traffickers to personalise traps. “Trafficker sees that the girl is interested in music and he keeps praising the girl’s voice,” says Kant.

No popular platform is untouched by traffickers, says Bhagwat. “Think of any platform… WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter… I have seen it everywhere.”

FactorDaily has approached Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter seeking comments on the issue. While we are awaiting replies from Facebook and Twitter, a WhatsApp spokesperson said the platform is mainly used by people who know one another’s phone number. “We do not provide a search function for people or groups. We also make it easy to block users with one tap and encourage users to report problematic messages so we can take action.”

.

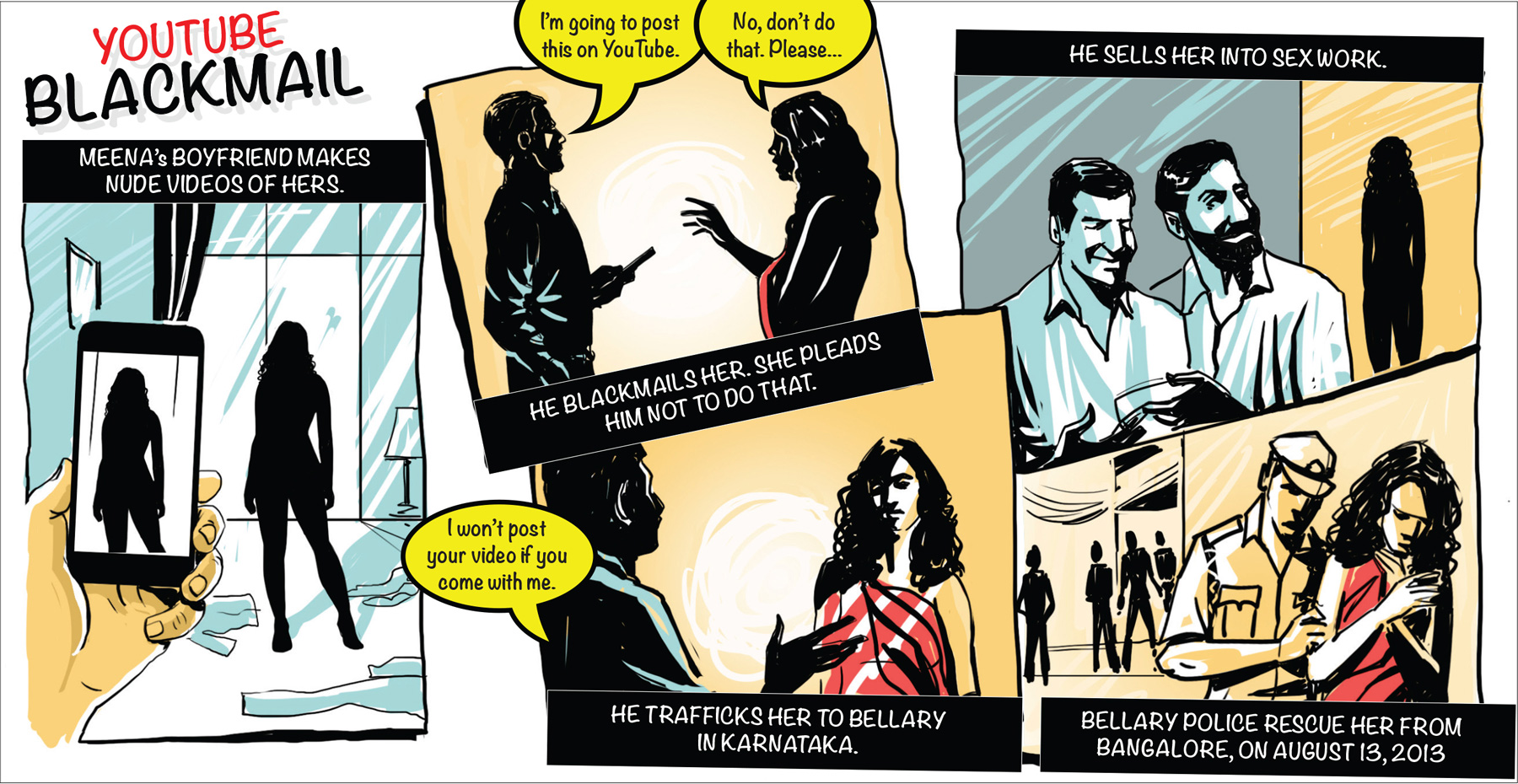

Meena, an Adivasi girl from a small village in West Bengal, fell in love with Mamai from the same village. One day in 2012, Mamai drugged Meena, then 18, and recorded nude videos and photos of her. He threatened to leak those videos on the internet if she didn’t come with him. Mamai trafficked her to Bellary in Karnataka and sold her to a brothel-owner. Meena was forced to attend 10-15 customers every day but was not paid. Mamai, who now stayed in the same area, collected her earnings. Meena had no contact with her family. On August 13, 2013, Meena was rescued by Bellary police.

Technology is ethically neutral. Most tech platforms are just tools of convenience. But in a trafficker’s hand, they turn into instruments of evil, providing them with new, efficient and, often anonymous, ways of exploiting women. Today, digital tools are used in every aspect of trafficking.

A trafficker can transport a victim without physically being with her and thus avoid public attention. A minor girl from Bihar travelled all by herself to Delhi under a trafficker’s constant instructions conveyed on WhatsApp. Traffickers often use GPS locations of phones to track a victim’s movement.

Next, the victim is retained through physical abuse, shaming, and blackmail. Traffickers record nude photos and videos of victims to force them into and chain them in sex work. In some cases, traffickers use porn videos to train young girls for sex work. “They show porn videos to young children; they train them to behave in a way to entice customers,” says Kant.

Grooming, transporting, retaining and selling victims require a huge amount of coordination within the trafficking network. Now, the internal communications of trafficking networks have moved fully to WhatsApp, behind the safety wall of encryption. “From small brothels to big and organised agencies, all use WhatsApp to communicate with their agents and recruiters. They avoid phone calls since those can be tracked,” Kant says.

Most of the traffickers who participated in Sarkar’s survey (59 out of the 64 – or 92%) adopted mobile phones to keep contact with commission agents to finalise deals. Over 72% of them (46) changed their mobile numbers frequently to avoid detection. A few preferred face-to-face conversations with the agents for fear of call-tapping, but they were not scared of making internet calls.

Now, the next important task is to get the word out to customers. Technology has shifted the selling from the street to online. Any website or social media platform can be used by employing the right code words — like “new in town” would mean a new victim, often a minor. The regular clientele is familiar with the codes.

Sarkar’s work showed that several clients searched for victims in chat rooms, especially ones meant for young people. Some clients with an interest in trafficked victims said they sometimes worked together online with other clients, helping each other find victims.

To draw the attention of potential clients, traffickers advertise on search engines and websites with free pornography. They use pagejacking (replicating a legitimate website by stealing its looks and content) and mousetrapping (trapping a visitor on a website by launching an endless series of pop-ups) to misdirect users to land on the traffickers’ web pages.

Every sex racket has its circles of regular and select clients. They prefer group communication. Bhagwat of Rachakonda Police has found several escort services that use victims of trafficking on WhatsApp groups and Facebook pages — some closed and some open. Sex rackets post photos and videos of girls on WhatsApp groups to solicit clients. Clients can browse through ‘catalogues’, pick a girl, and offer or accept a price.

Most sex rackets even book rooms for clients. Jharkhand Police have found several cases where these rackets booked rooms using popular hotel-booking apps.

Once a deal is struck comes the final leg of the job — money transaction. Historically, sex work has run on cash despite issues such as clients haggling over payments, getting into fights, and even robbing sex workers and pimps of their cash.

Now, to ensure payment, sex rackets are increasingly asking customers to pay online. Sometimes the money is moved through multiple accounts before being withdrawn by a hired pawn. In many cases, bank accounts are opened and shut in a matter of days after withdrawing big sums deposited by clients or agents. In Sarkar’s survey, 56% of the clients who participated (48 out of 85) said they paid online.

Technology also facilitates illegal exchange of money. Some legal businesses act as fronts for trafficking networks and sex rackets, says Kant. Bennett of Destiny NGO, who previously was a strategic technology adviser with San Francisco-based Salesforce.com, expects to see increased use of cryptocurrencies to trade between criminals.

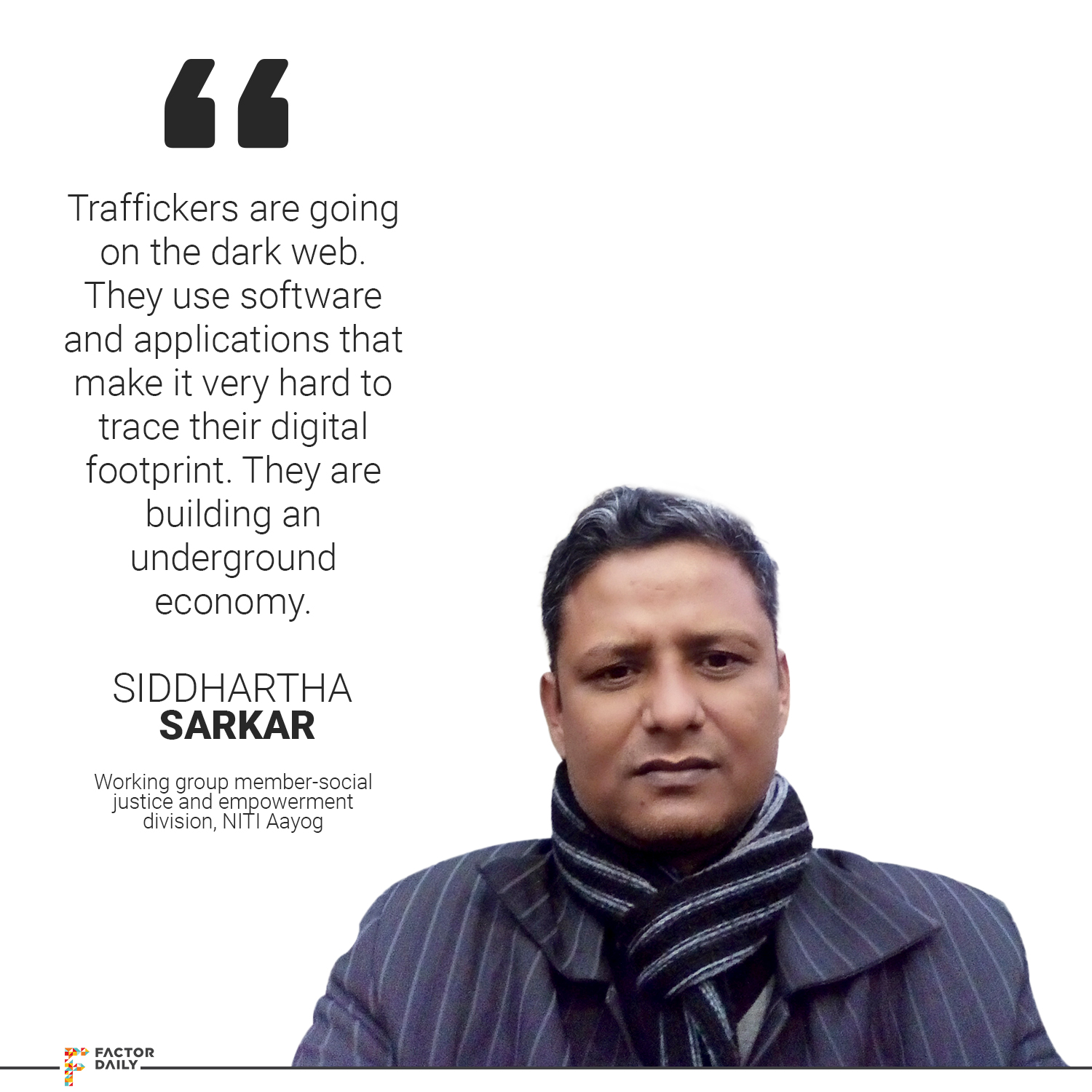

Sarkar insists traffickers in India have begun using sophisticated technologies and encrypted websites. “They’re going on the dark web. They use software and applications that make it very hard to trace their digital footprint. They are building an underground economy,” he says.

Bennett’s and Sarkar’s claims are backed by the police.

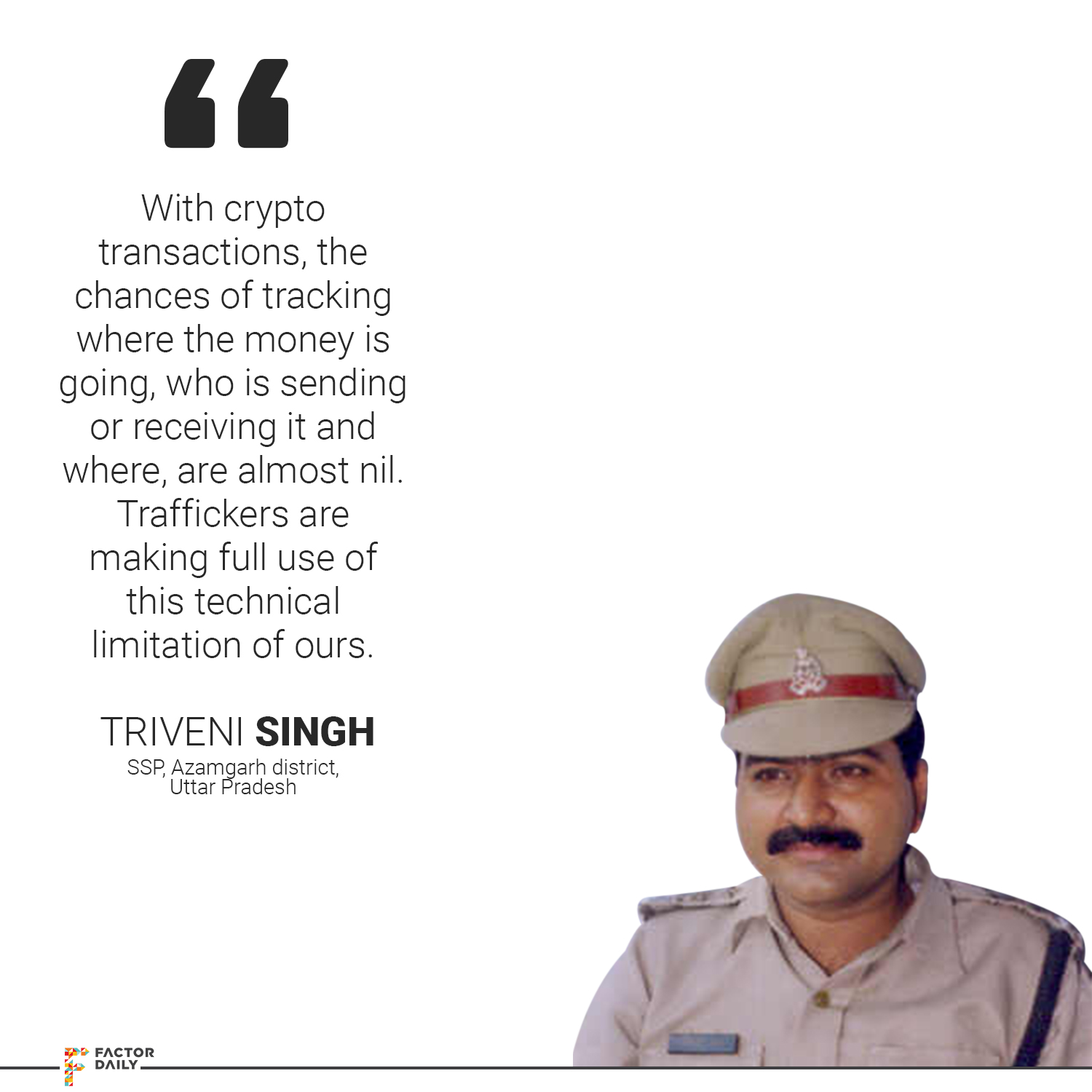

Police officer Triveni Singh, who specialises in cybercrime and financial fraud, confirms there are a lot of instances of Indian traffickers using sophisticated technologies. On whether they are operating on the darknet, he says: “Definitely! Without a doubt.”

Singh, presently Senior Superintendent of Police, Azamgarh district, Uttar Pradesh, says traffickers don’t have to be tech-savvy to do this. “There are enough and more tools and applications available that they can install and use. Many rackets are purchasing virtual numbers. With these numbers, they operate on WhatsApp. Also, there are too many private messaging services to keep track of. They use spoofing (sending communications from unknown sources disguised as a source known to the receiver),” he says.

India faces an urban-rural divide as well as a gender gap in mobile and internet access. However, rural India is the next area of growth for mobile internet. Over 35% of 4G subscribers are in rural areas. With Reliance Jio making mobile internet more accessible, rural India is getting online faster than ever. Also, mobile internet is predominantly used by youngsters, with 46% of urban users and 57% of rural users being under the age of 25. Once women have access to mobile internet, they are as likely to use internet services as men. According to the GSMA Intelligence Consumer Survey, 2017, among women mobile internet users, 49% use social media, 44% use apps, and 57% use video calls.

The intersection of this population – young, female, rural – is the target of sex traffickers.

The growing pervasiveness of internet connectivity and mobile technologies mean that more people from the most vulnerable groups are now potential targets of traffickers, says Bennett. “Many young people are unaware of the dangers online and risk being lured into a dangerous situation.”

The wide reach of technology and ignorance of safe online behaviour is what makes India particularly vulnerable to technology-facilitated trafficking. “We’re giving computers and internet to our children but we aren’t teaching them how to keep themselves safe online,” says Tapoti Bhowmick, senior programme coordinator at Sanlaap, an anti-trafficking NGO based in Kolkata. “In fact, parents themselves have little knowledge of online sexual abuse and online trafficking. Parents and schools both fail in teaching children how to behave online.”

How we train and educate the most vulnerable to use technology safely, and be suspicious of strangers on the internet, is going to be a key challenge for India, says Bennett.

Manish Kumar Singh, under secretary in the Ministry of Women and Child Development, says the department is aware of the gravity of the problem of tech-enabled sex trafficking. “The ministry is implementing (the) Ujjawala scheme, a comprehensive scheme for prevention of trafficking with five specific components — prevention, rescue, rehabilitation, re-integration and repatriation,” he says in an email. “Awareness generation through digital communication and social media aimed at prevention of trafficking is proposed in draft guidelines of Ujjawala scheme under prevention component of this scheme.”

Working with companies located outside India has been particularly troublesome for the police in fighting sex traffickers. This includes tech giants like Facebook and Twitter.

In most cases, the servers are located outside India, complicating evidence-collection. Requesting the company that hosts the server is a very long process, going through the police, the local magistrate, the Central Bureau of Investigation, and the ministries of external affairs and home affairs before it reaches the host country. In the host country, the request is processed by the justice department, a local magistrate, local police, and then the company that hosts the server.

“When the server is located outside India, sometimes we get meta logs, IP addresses, etc., but we are never able to access full information. We just can’t trace the criminals in such cases,” says Singh of UP Police.

The darknet and crypto transactions make tracing criminals even tougher. “The chances of tracking where the money is going, who is sending or receiving it and where, are almost nil,” says Singh. “Traffickers are making full use of this technical limitation of ours.”

Bhagwat recounts several instances where his team informed Locanto.net about the use of trafficking victims in their ads for escort services. “They just delete that one ad you complain about and do nothing about similar ads. A lot of times, the same ad pops up the next day, with a new name or phone number.”

Emma Cruz, communications manager at Locanto, said the company uses “advanced technology (including artificial intelligence) to automatically detect and remove bad ads from our site. “Additionally, we improve our control mechanisms with new indicators and introduce automatic rules on a regular basis in order to effectively identify and fight such practices. Furthermore, we carry out random spot checks to control the content published on Locanto.”

All that’s not been adequate, though, in weeding out illicit ads. “Unfortunately, it is not always possible to detect these type of ads at first glance. The ads usually seem to be in order and their illicit nature only becomes apparent when the contact between an ad poster and a user takes place,” Cruz said in an email, adding that users can report suspicious advertisers, communications, and behaviours.

On September 11, 2017, unexpectedly for her family, Farzana turned up at her home. She told them she was fine but they suspected she was in trauma. Later, they found cigarette burns on her. Still scared of her tormentors, Farzana asked her mother to withdraw the complaint filed with the police. Her mother wasn’t convinced. Eventually, the family coaxed the real story out of her.

When the police raids began at GB Road in search of Farzana, the pimps at the brothel (no. 56) she was kept at moved her to another one (no. 58) that had Bengali girls. She was confined in a room. Manju and Riya asked her if she had informed her family and beat her. They brought her back to the first brothel (no. 56) but moved her again during the next raid. Clearly, someone was tipping them off.

When the police couldn’t find Farzana after two raids, the Delhi Commission for Women issued summons to 125 brothel owners on GB Road. Manju and Riya brought Farzana to Muniya’s house in Ghaziabad. They beat her mercilessly and burnt her with cigarettes. Finally, to get the police off their back, they asked her to go home, withdraw the case, and return.

Farzana pleaded with one of her regular customers to accompany her to Kolkata. He dropped her at Sealdah railway station, gave her Rs 2,000, and some food. From there, Farzana found her way to Diamond Harbour and managed to get home.

Farzana’s mother convinced her to record her statement with the police. Within three days, she was produced before a CWC in South 24 Parganas, which sent her to a shelter home for a month. She decided to focus on her matriculation exam. She had missed out on her academic session for over five months.

With the West Bengal government’s Kanyashree scheme – cash support for underprivileged girls – and educational support for her board exam, Farzana bucked up. By the end of October, she was reunited with her family.

On December 15, 2017, Farzana left for Delhi with her mother. West Bengal and Criminal Investigation Department police accompanied them. The next day, in Delhi, she met Kant and another member of Shakti Vahini. Kant and the police decided to locate Muniya’s house in Ghaziabad where Farzana had been first confined and raped.

Farzana said she could find the place by retracing the route she took with Sabir from Ghaziabad railway station. Wearing a burqa, she set out with the police in tow. She recalled Sabir had taken an auto from the railway station, and then, changed the auto at a major traffic circle. But she couldn’t find the location. After some time, she reached a street that seemed familiar — ‘Aata chakki wali gali’.

By then, it was already midnight. Despite the freezing December winter, Farzana walked around the street for an hour. Still, she couldn’t find the house. The search would continue the next day.

This time, they decided to start from the railway station. Farzana, along with a member of Shakti Vahini and one constable, boarded an auto to find the traffic circle. After 40 minutes, she found it. She took another auto for Loni. She told the auto driver she didn’t have the address but could identify the place by sight.

At Loni, Farzana asked to deboard at a square; this was the place. She recognised a street and went inside. The police followed closely.

There were houses on both sides of the street. A little ahead, she reached a narrow lane. Muniya’s house was in that lane, she told the police. It was 5 pm. They decided to raid later in the night and went back to Delhi.

At 10 pm, the team, along with Farzana, went to the local police station to ask for assistance as the house fell in that station’s jurisdiction. After a long process of formalities, and pleading and convincing by Shakti Vahini and West Bengal police, a seven-member team of UP police accompanied them to the lane. Farzana stopped in front of a two storey building. This was the house, she said.

Two members of UP police went to the terrace of the neighbouring house; another knocked at the door. When nobody answered, the police forced themselves inside. There was nobody on the ground floor. But on the first floor, they found a woman and two men.

Farzana stepped forward and slapped the woman.

This is Muniya, she announced. The two men were her sons, Vinit and Sonu. As she spoke, Farzana began shivering and then fainted. She regained consciousness after a while.

The three accused were perplexed. They didn’t recognise Farzana as she was in a burqa.

The police arrested Vinit, Sonu and Muniya and brought them to Loni border police station. It was only then that Farzana removed her veil. The revelation astounded the accused.

Farzana slapped Muniya again.

Next, the team wanted to arrest the people who had forced Farzana into sex work. They left to raid the two brothels where she had been held.

By now, it was 3 am. They raided kotha no. 58. Farzana identified brothel-keepers Manju and Riya. The West Bengal police arrested them. Then, at 3:45 am, they raided kotha no. 56. But the police couldn’t find the brothel-keeper Bhanu.

The next day, the West Bengal police and the five accused left for Kolkata by train.

Farzana and her mother were on the same train.