“TikTok is a Youtube killer.”

“Helo is giving ShareChat a tough time and has a higher chance of winning India market.”

“TikTok is like Instagram for India.”

“Bigo Live is a platform for companionship.”

For those trying to make sense of the Chinese dominance of the Indian app ecosystem, these are familiar statements. Yet, until about a year or a little more ago, these platforms and their Chinese parents were not heard of.

Now, they are not just a rage but have inspired several dozens of other platforms to launch and experiment in the internet booming India market.

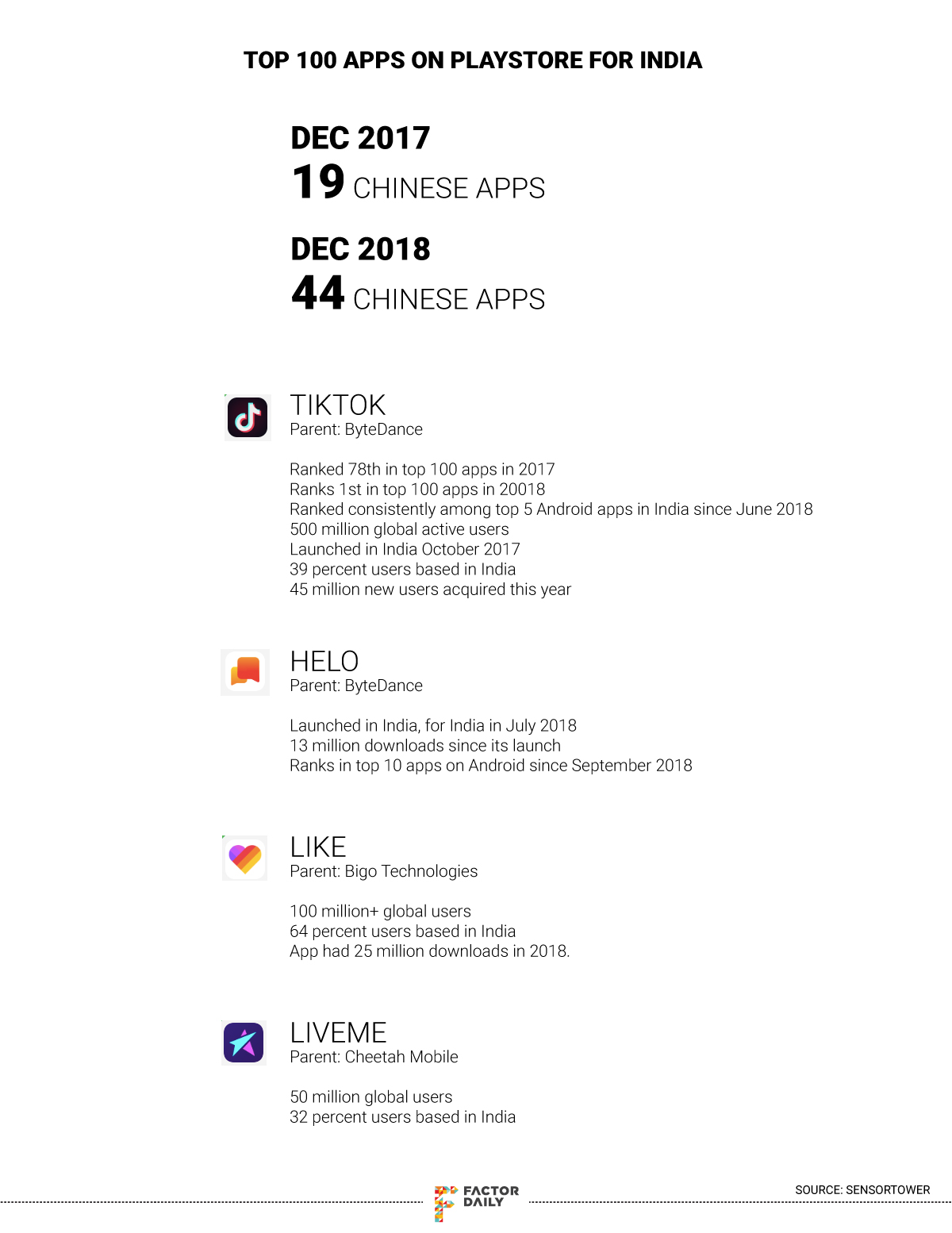

2018 is likely to be remembered as the year when the Chinese took over Indian smartphones. In December 2017, the top 10 mobile apps on Google Playstore looked a lot different than what they look from a year later. The Playstore rankings for India in 2018 have China written all over it. Five out of the top 10 mobile apps in India are Chinese — versus two at the end of 2017.

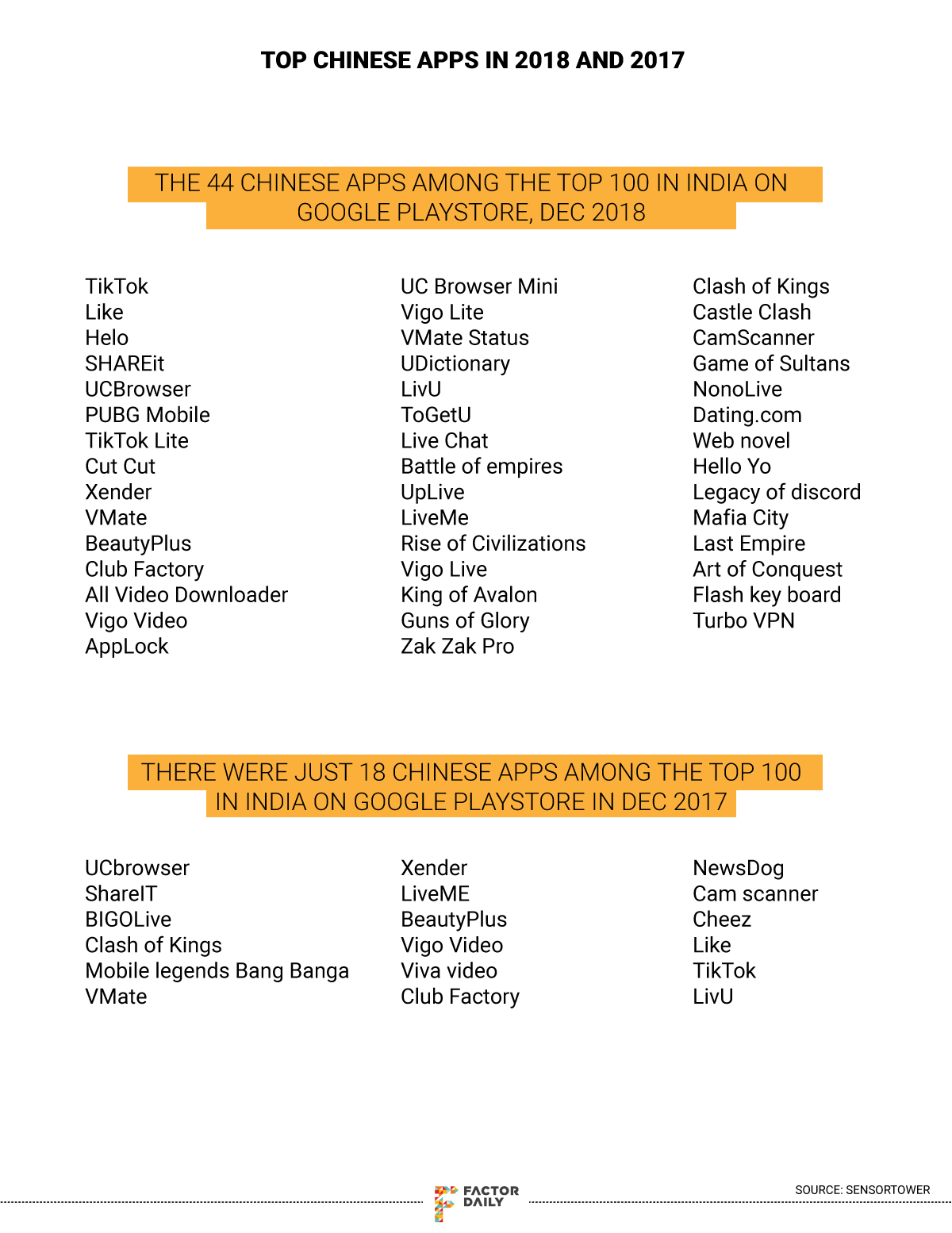

That’s not all. As of December 2017, there were 18 Chinese apps among the top 100 across various categories on Google Playstore. These included popular ones such as UCBrowser, SHAREit, and NewsDog. Fast forward to the end of 2018. The number of Chinese apps in the top 100 Playstore apps has reached 44. Beyond the top 100, there are others like Rozbuzz, a social entertainment content platform, and YouStar, a video chat room platform, that enjoy a more than one million downloads in India – a threshold that evokes grudging respect in this app community.

The growth of many of these global apps has a new hotspot: India. The message is clear for the Chinese — if you want growth, conquer India.

Several Chinese apps have become significantly popular over the last year in India: social content platforms such as Helo and SHAREit; entertainment and engagement apps such as TikTok, LIKE, and Kwai; video and live streaming ones such as LiveMe, Bigo Live, and Vigo Video; utility apps such as BeautyPlus, Xender and Cam Scanner; gaming leaders such as PUBG, Clash of Kings, and Mobile Legends; not to forget popular e-commerce apps including ClubFactory, SHEIN, and ROMWE.

A starking similarity not missed by observers of this industry is the target group of most of these platforms is the new internet users in India, specifically those from smaller cities and towns. To be fair, this market was first recognised by Bengaluru-based ShareChat that was founded back in 2015.

Homegrown ShareChat now has a total of over 50 million downloads as compared to Chinese giant ByteDance’s Helo that has about 10 million downloads. It’s important to note that ShareChat was founded in 2015 and grew along with the market for regional content. Helo, launched by ByteDance in July 2018, has shown better traction in its initial months in India. Data from app-tracker SensorTower shows that Helo had 13 million downloads since launch, whereas ShareChat was downloaded nine million in all of 2018.

LIKE a social video app by Bigo Technologies, that has over 100 million downloads has 64% of its total users based in the country. A social platform that hosts short videos of 15 seconds, similar to TikTok, LIKE had 25 million downloads in 2018.

TikTok, also owned by ByteDance, has consistently ranked among the top 5 Android apps in India since June 2018 and counts 39% of its over 500 million global active users from India – making this country its largest market. For comparison, 10% of TikTok’s total user base is based in the US. TikTok added 45 million users in 2018, per SensorTower data. The US, no surprises here, accounts for 56% of TikTok’s revenue while India’s contribution is just 3% in 2018.

LiveMe a live streaming broadcast app by Cheetah Mobile has 32% of its total 50 million users based in India.

“For Chinese companies in any sector, India is the only market that has the possibility of being as big as their market. There’s no other market that’d even come close,” says S. Ramakrishna Velamuri, professor of entrepreneurship at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai. Velamuri, who is leading entrepreneurs from China on an India tour this month, says the Chinese are increasingly seeing immense opportunities in India as a market for consumer-facing businesses.

There are many things that are common between Chinese apps launching in India: deep pockets for marketing expense, focus on vernacular India users, an addictive user interface, racy content, quick iterations and execution cycles, and cheap offerings to name a few. Also, there’s a huge emphasis to shed the “Chinese” tag. This could be an effort to address the general mistrust among Indians of Chinese products or a precautionary PR exercise.

In 2012, when Tencent’s relatively popular messenger WeChat launched in India it spared no expense in marketing and branding of the product. From product launches in malls to roping in popular Bollywood actors as brand ambassadors, WeChat launched and acquired users with commendable speed. But as the platform started getting more mainstream in China, its growth in India tanked. By 2015, Tencent wound up its WeChat team in India.

“A lot of it had to do with failing to localise the platform for India,” says Himanshu Gupta, former associate director of marketing and strategy, WeChat India.

Nevertheless, WeChat’s failure presents learnings for the Chinese ambitions of making India their next big market. Not only are Chinese entrepreneurs aware of it, but they also understand the nuances of the India market. This is evident from the strategy adopted by popular Chinese players in the India vernacular content market. For example, Helo by ByteDance has a local team entirely based in New Delhi.

“ByteDance which is focused on content interaction platform play saw immense opportunity in India,” says Shyamanga Barooah, content operations head at Helo.“But Helo is totally independent.”

ByteDance might be the holding company but it understands that there is no one-size-fits-all approach at play. The India audience doesn’t fit into the strategy that worked in China which is why Barooah, a former reporter and editor at mainstream Indian news media outlets such as India Today and The Hindustan Times, says he works on the ground with content operations, moderation, marketing, hiring, and all other aspects to have a localised strategy.

NewsDog, an early entrant from China in the India content market, first launched its entertainment content aggregator app in 2016 only in English. But, months after the launch, Forrest Chen, the founder of Hacker Interstellar, the company that owns NewsDog, visited India and found that even among urban Indians or Indians living in Tier 1 cities, there was an overwhelming number of regional language speakers.

As part of his tours in India, Chen did surveys often speaking with restaurant doorkeepers and cab drivers to understand the nuances of the market and modify his platform to suit the needs of Indian consumers. The company is on its way to launch half a dozen new apps in the India content market in the coming year.

Chen said that over the course of last couple of years video viewing has exploded in India and his company is working on a bunch of video platforms with long and short form content available in vernacular languages to serve the Indian audience. For example, an app that hosts only Tamil and Telugu video content, mostly movie clips, is in Beta stage now.

Another popular Chinese platform deeply rooted within Indian vernacular consumers SHAREit is extremely bullish on its India growth story. “For someone like WeChat that’s like a giant in China, India market might have been an option,” says Jason Wong, SHAREit India managing director. “But for us India is the main market. If we lose India market, we need to shut down our business.”

SHAREit, which has a 300-member-strong team in China and 60-member team spread across Bengaluru and Delhi in India, is also planning on moving its research and development to Bengaluru in India in order to have more cohesion between its market requirements and corresponding platform offering.

“What’s the image of India in your head,” asks James Crabtree, author of The Billionaire Raj, a book on the rise of India’s new billionaire class.

“It’s an image of inequality. People know about the caste system. They know about extreme poverty. There’s a lot of other inequality in India. The south is richer than the north. The cities are richer than the villages, but it’s almost because we all think that India’s a very unequal place, we haven’t noticed how spectacularly more unequal it has become over the last 10 or 15 years,” Crabtree says in this podcast of Recode Decode.

In his back-to-basics analysis of the Indian economy, Crabtree, a former Financial Times reporter and currently professor at the National University of Singapore, has interesting takes for businesses eyeing the next 400 million – or India2 or Bharat – consumers. These are the new internet users, residing in Tier 2, 3 or 4 towns and villages, who speak vernacular languages, and have modest incomes. These consumers don’t speak English, but they don’t speak one unanimous language either. These consumers are segregated – nee nuanced – by geographies, languages, income parity and interests.

“If you break India into a pyramid, the top 100 million (urban) consumers who think and behave more like Americans are well-served,” says Amit Jangir, who leads India investments at 01VC, a Chinese venture capital firm based in Shanghai. The early stage venture firm has invested in micro-lending firms FlashCash and SmartCoin based in India.

The new target is the next 200 million to 600 million consumers, who do not have a go-to entertainment, payment or ecommerce platform yet— and there is gonna be a unicorn in each of these verticals, says Jangir, adding that it will be not be as easy for a player to win this market considering the diversity and low ticket sizes.

Companies at the forefront of this battle including Helo and ShareChat are experimenting with different strategies to increase user stickiness on their platforms. Helo is launching verified profiles and partnering with celebrities to drive more users to the platform. ShareChat is partnering with political parties as part of their digital campaign strategy.

Platforms such as LiveMe and TikTok that have garnered a decent user base in India are looking at exploring possible monetisation avenues from India market.

LiveMe has set up three studios in India where it is creating content using local talent likely to be monetised later. Largely growing to be the next big social platform, TikTok is also looking at growing influencer marketing in India by partnering with brands and enabling top influencers to partner with brands for advertisements. This means we are likely to see shows coming on live streaming platforms and content commerce happening through TikTok.

“A possible reason a lot of Chinese companies are targeting Tier 3-4 towns is (that) a lot of internet consumption is habit-based,” says Gupta, the former WeChat executive, who now heads growth at Walnut, personal wealth management platform. Most of the new-to-internet population in India is coming from these places which is not used to YouTube and other platforms yet. So, there is an opportunity in getting habits created, he says.

For sure, it’s a young market. Several platforms have been using aggressive marketing lures like providing cashback or enabling users to earn money by spending time on the app to increase downloads and time spent on the platforms. The numbers also indicate the popularity of these platforms. But it’s a long way to go before these numbers actually start yielding revenue for these platforms.

Sajith Pai, a director at Blume Ventures, is of the opinion that among the Chinese players trying to capture the social content space in India, TikTok has a higher chance of emerging as a winner. He says that the content on TikTok navigates well enough to service both consumers from India1 and India2 and the algorithms powering the platform will continue to make it addictive.

“Ultimately the player that is able to attract and incentivize creators and not just consumers, is likely to win in the long run,” says Pai. (By way of disclosure: Blume Ventures is an investor in Sourcecode Media Pvt Ltd, which owns FactorDaily.com. Pai’s hypothesis on India1 and India2 markets can be seen here.)

China’s economic and technological growth in the last few decades has been nothing short of a miracle. It has put the Middle Kingdom in such an enviable position on the enterprise map that even large global companies like Google and Facebook have taken a leaf out of the Chinese giant’s playbook. For example, Amazon and Facebook segueing into bank accounts and music, much like China’s e-commerce giant Alibaba dominating the finance play through Alipay or Tencent’s successful foray in the music industry.

As is evident in 2018, the Chinese playbook is not just recommended reading for Silicon Valley companies and executive. Back home, as India surges ahead with its world’s second largest internet market status, large and small internet companies from China slowly yet surely are having Indian apps for breakfast – deploying, well, the Chinese playbook of content, community, and commerce.

A top executive who previously worked with Tencent in India and did not wish to be named says that the Chinese playbook of launching a platform in a new market is largely about getting three things right.

The first is housing relevant and engaging content. In the case of popular Chinese apps in India such as Helo, TikTok, and LiveMe, the strategy has been to focus on user-generated content. This solves their challenge of creating local and relevant content.

The second part is based on technology localisation, largely focused around improving the performance of the product. For example, apps including TikTok and Vigo have a “lite” version of their app for a market like India that is plagued with low bandwidth and sporadic connectivity challenges.

The third bit which serves more like a later stage requirement is to do partnerships in the local market, including tie-ups with music and media companies.

“From the time when WeChat launched in India market to the recent new ones that are launching now, the playbook has more or less stayed the same, though the market is much different now,” this person said.

The Chinese style of business is very different from the Silicon Valley way of doing things, says Ranjeet Pratap Singh, founder of self-publishing platform Pratilipi. The platform focuses on regional literature and vernacular writers and counts Omidyar Network, Nexus Venture Partners and China-based Shunwei Capital among its backers. “Chinese companies usually focus on the scale first and defensibility later. Valley focuses on defensibility first and scale later,” says Singh. By defensibility, Singh means the value proposition or business model of a product or platform.

Singh’s observation seems on point if you look at the growth the Chinese platforms in India have achieved only in the last year.

The challenge that comes along with this growth is, however, to keep a check on means to achieve this growth. The content on many of these platforms, including Like, Kwai, TikTok, NewsDog, and SHAREit often crosses the line when it comes to racy versus risque. Scantily clad women dancing invitingly, pictures of hot photo shoots of actresses, and little girls miming inappropriate lyrics abound on these platforms. Not to mention, bullying, body shaming and crass commentary that’s the new normal on these platforms.

These platforms have run into challenges with their content elsewhere in the world, too. In July last year, LiveMe said it deleted over 600,000 accounts of children under 13 after a TV news channel talked of the dangers of paedophiles exploiting children.

“The Chinese have been wise enough to understand the video opportunity on top of the data revolution in India,” says Gupta. The Chinese also realise that there is room for new consumption and creation models here, which is apparent in the kind of aggressive experiments they’ve been doing.

Gupta says that while ShareChat and Clip India have done some decent work in India around the entertainment opportunity, Indian players have usually been very conservative compared to their Chinese counterparts who have been willing to push limits when it comes to issues like piracy, sensational content bordering on porn etc.

“An Indian founder promoting piracy or porn platform is likely to be put in jail. In the case of a Chinese company, it would at worse shut its India operations,” he observes.

So, a Kwai may take a view that it would aim for engagement and critical mass first, and then solve difficult content moderation issues later, he says.

[Read our story on How Kwai turns a blind eye to videos of underage girls on its platforms]

Gupta, however, argues that not all Chinese companies take the same approach. For example, companies such as Tencent or Xiaomi that are invested in India for the long haul are more measured in their approach.

While the content on Chinese apps remain a topic of controversy among the Indian technology and startup circles, there has also been an increasing reverence towards the sophistication of some of the Chinese platforms.

“If you look at some of the Chinese products like TikTok, there is very high level of technological sophistication that Indian platforms lack,” says Akash Senapaty, a product manager at Zynga and an expert at taking apart apps. “There’s a high visibility of these products in India now and Indian product people are definitely looking to learn from these products.”

If Indian app entrepreneurs can make good learnings from the Chinese invading their fief, it may stem the hollowing out of the Indian app ecosystem.