Akshay Kakkar is a mini celebrity. With over 45,000 fans on TikTok he has become a popular household name in Shahdara in east Delhi. His images on the Chinese video platform shows a chubby man in his early twenties dancing to the popular Meri neendein hain faraar and Mujhko hui na khabar Bollywood songs.

By Kakkar’s own admission, he is overweight. Yet, his dancing videos memes rank way above those of conventionally beautiful girls – fair, svelte, and dolled up – swaying to the same songs, he says, chuffed with his recent popularity on TikTok.

Kakkar, 23, has dealt with bullying, fat shaming and taunting remarks on his choice of songs and an unmanly dancing style in the past. The last six months have been different: a whole new life of respect and recognition after he started posting on TikTok. He has made new friends, been contacted for dancing lessons, and even found a girlfriend through the platform.

“There are still a lot of people who have the vilest things to say on my dancing videos,” Kakkar told me a few weeks ago. “But those comments are dwarfed by the number of positive comments and support I get on TikTok.” Some days later, he was offered an appearance on a reality TV show. He’s not allowed to name it.

Kakkar calls the audience on TikTok kinder. It prefers talent over pretty faces and well-toned bodies, he insists.

Self-serving as it seems, the freelance science tutor may have made an astute observation.

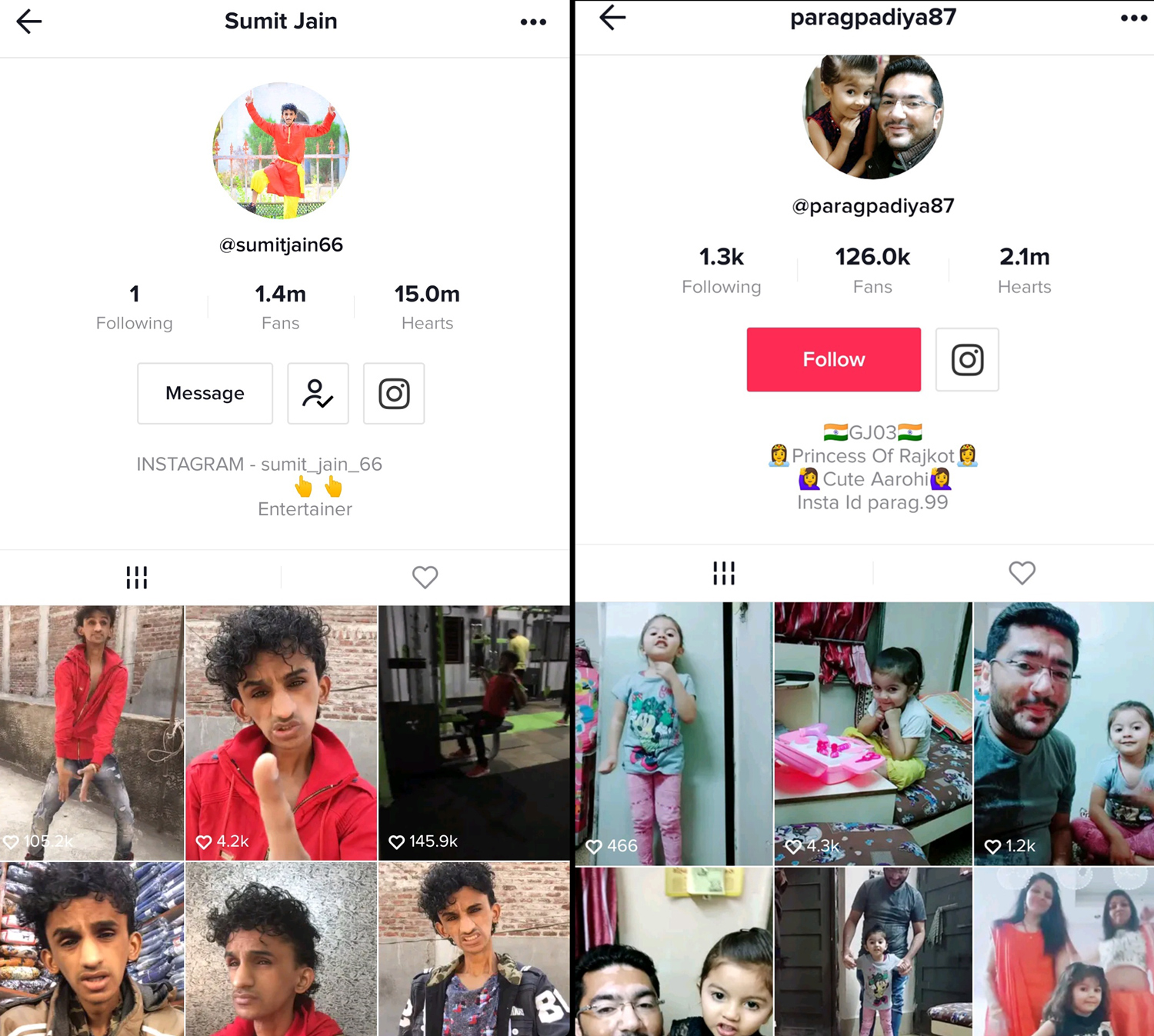

Parag Padiya who has 126,800 fans on TikTok agrees with Kakkar. Padiya who posts videos with his three-year-old daughter Arohi, has vitiligo, a condition that causes the skin to lose colour in patches. His wife and Arohi, too, have vitiligo. The family gets a huge amount of support and appreciation on their videos. “Our followers love me and my daughter,” he says. Once when he posted a black and white video, Padiya’s followers urged him to not let his skin condition hold him back.

“I was using a black and white filter to create an effect and not to hide my skin condition. But the support of people who told me that they are accepting me the way I am, still meant a lot,” says Padiya, 32, an account executive at a local firm in Rajkot.

Kakkar and Padiya may not realise that the “kinder” and “accepting” qualities they see on TikTok are but markers of a subtle change in the consumption of social media platforms in India. If a few years ago Instagram was the go-to platform for India 1 – as the top 100 million Indians by wealth are often called – TikTok has muscled into the sweepstakes with a formidable following in India 2 and India 3, the next 100 million and 1.13 billion Indians respectively. The India 1, 2, and 3 framework is often used by analysts while looking at purchasing power of Indians and how businesses sell to them.

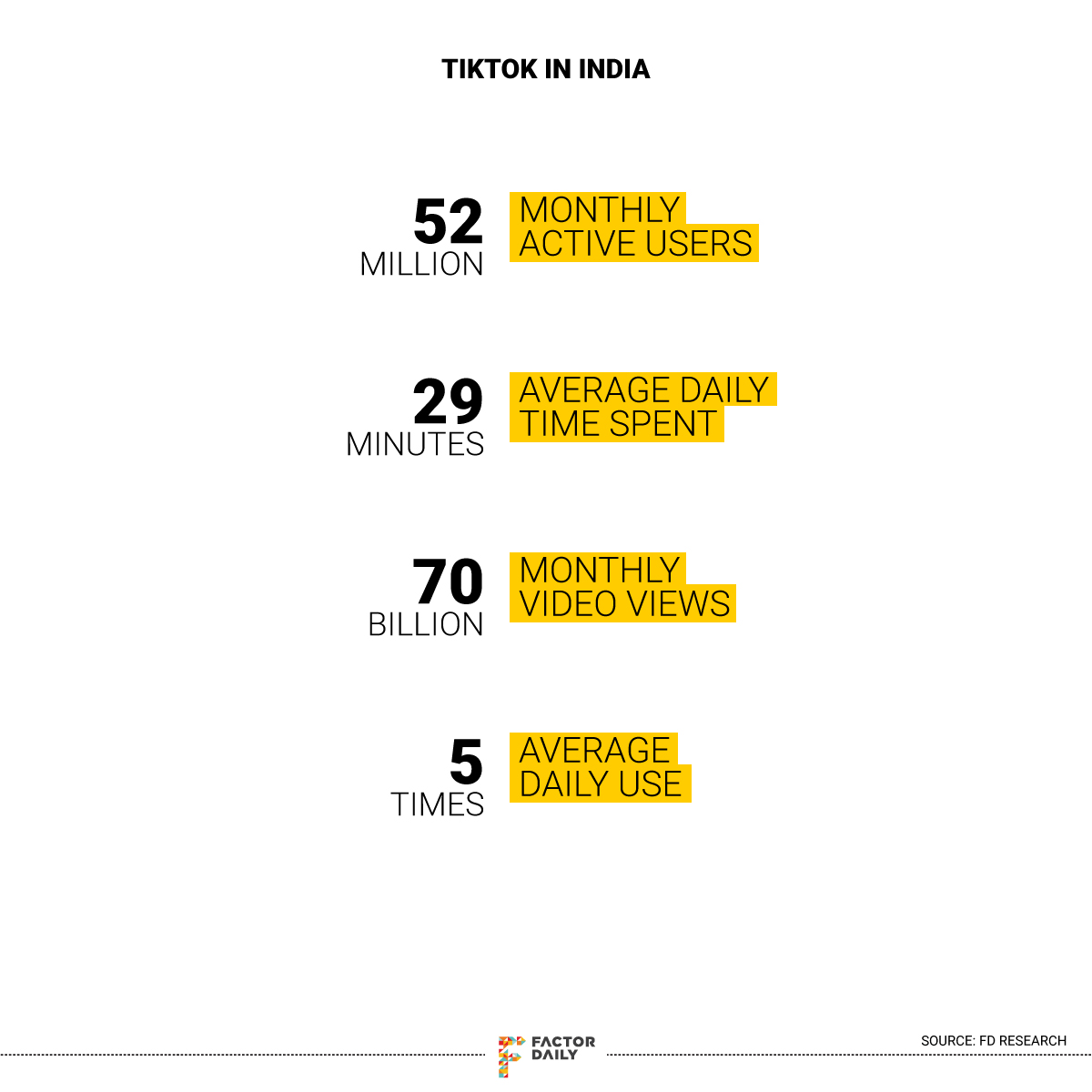

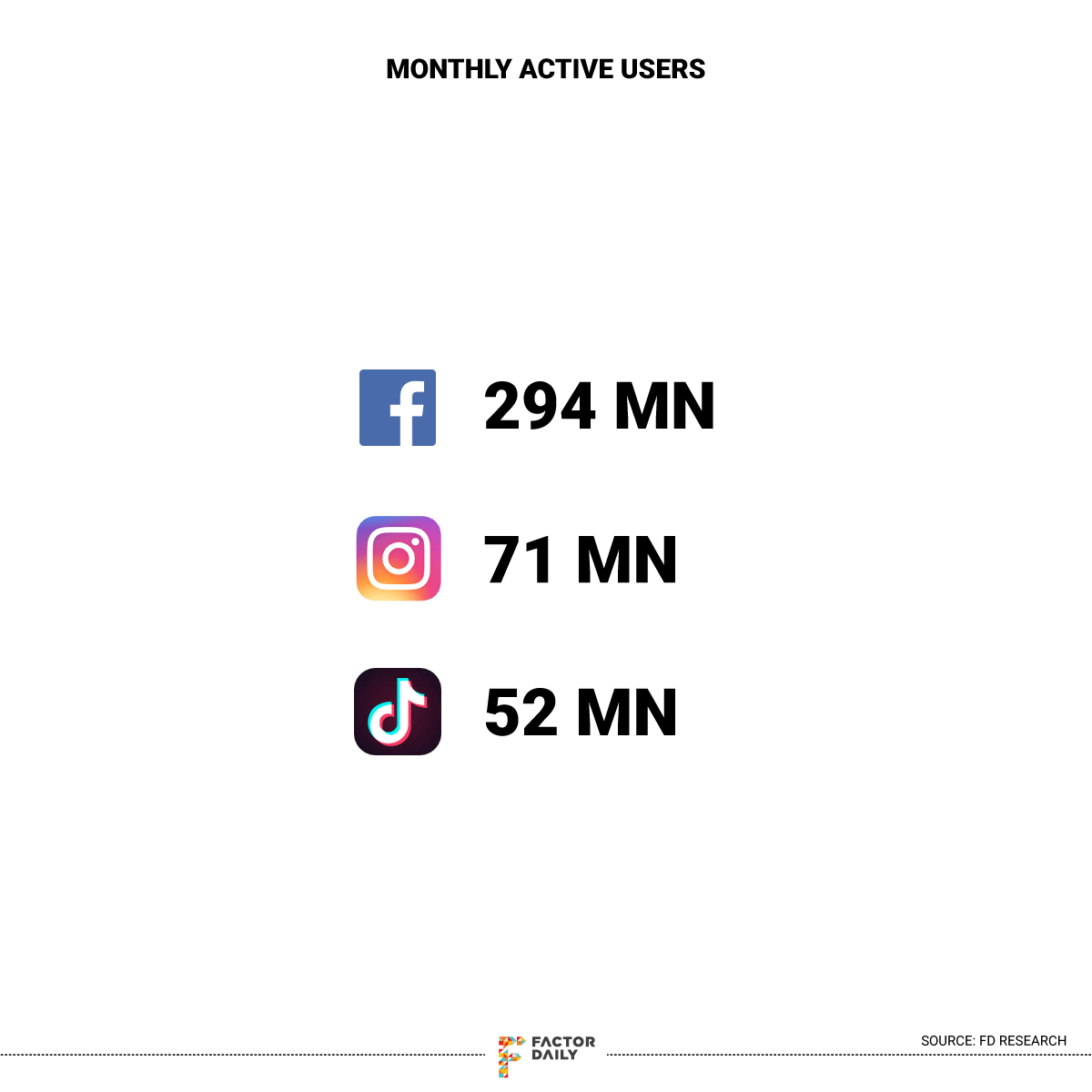

The numbers speak volumes: Instagram has over 70 million so-called monthly active users in India (those who log on at least once a month), while TikTok has crossed 52 million MAUs last month, according to a presentation the platform made to advertisers.

And, what’s the subtle social media transition that we talked about earlier? If Instagram was the destination for all things beautiful that India’s upper and wannabe classes flocked to, TikTok is rooted in hinterland India with a focus on talents sans make-up or filters.

Noopur Raval, a researcher of digital platforms, calls the two platforms “a case of massy versus classy app”. The upper middle class has a conspicuous consumption culture where people seek to go up and to align to rich people, she points out. Which made Instagram a popular choice among this class.

But among poorer sections and lower middle class, the natural choice is to look for relatability and comfort in entertainment content, says Raval. TikTok speaks to them in terms of continuity. “This is the same world that you have seen in a Kapil Sharma show or a stand up by Raju Srivastav where crass, oddball or slapstick humour is appreciated,” she says.

“TikTok has organically identified the lower middle class segment,” she concludes. In other words, India 2 and 3 are its fief — and, given some common cultural tastes, TikTok’s success is slowly eating into India 1.

Much of India 1’s initial reaction to TikTok has been that it’s cringey. There are enough compilations on YouTube and Facebook of crying boys, oddballs and cringe-inducing miming videos made by teenagers to older men to overweight women. TikTok is home to popular creators who are not the best looking, presentable or even exceptionally talented as opposed to popular Instagram users who needs to look pretty and polished to make themselves and their lives look more glam than real. But, it’s the creator’s earnestness, as he or she sheds inhibitions, that makes the content sticky.

Take the case of Sumit Jain, a cloth store owner in Dhule, a Maharashtra town 325 km northeast to Mumbai. Let’s say Jain looks different. He will draw attention even in a crowd. He is leaner than most people and has an oddly elliptical face cut. The sinews on his neck stand out. But when he is dancing or mimicking a popular Bollywood actor, he transforms into an extraordinary performer — one that has 1.4 million fans on TikTok. A video of him bench pressing at a gym has over 184,600 likes and nearly 3,000 comments: from people cheering him to others poking fun of his frail frame to some taking his side against the naysayers.

Jain, 27, says the negative comments don’t bother him. They have been a part of his life. “If anything, negative comments motivate me to work harder,” he says.

A network like TikTok that celebrates oddities or uniqueness has given people like Jain a platform. His comic timing and dancing has even had a filmmaker reach out to him for a part in a movie, he says.

TikTok (earlier Musical.ly) that spread like a rage in the country in the last one year was more popular for its lipsyncing videos among teens. In fact, even before TikTok or Musical.ly, it was Dubsmash that introduced the concept of lip syncing in India and even globally. Dubsmash had its run among teens and even celebrities in India with very little marketing effort. From politicians like Lalu Yadav to Bollywood celebs like Salman Khan and Deepika Padukone, the German origin platform got a good push through popular creators on its platform.

Musical.ly the new kid on the block that got popular around early 2015 in the U.S, soon found its set of teenage users who flocked to Musical.ly to create lipsyncing videos and post them on other social media platforms.

The main reason for the decline of Dubsmash and the popularity of Musical.ly (now TikTok) was that the former was used mainly as a tool to create videos, says Himanshu Gupta, head of growth at Walnut, a personal finance portal.

“Dubsmash like the photo editing tool Prisma, was a popular tool to create content, but it never functioned as a platform to promote content – as opposed to TikTok or Instagram that stress on creating a community platform rather than just functioning as a tool,” says Gupta, who in a previous job was with the Indian unit of WeChat, the Chinese super-app.

That platform approach locks in customers and makes TikTok weirdly addictive. Its 52 million MAUs in India spend an average 29 minutes daily on the app. A first time user lands up on a full screen 15-second vertical video, without any sign-up on the platform. Swiping down vertically takes you to the next video and so on.

Once you have got the attention of your users, how do you keep their interest? TikTok’s answer is throwing relevant challenges at them. To a great extent, it has worked well for the Los Angeles-headquartered company that is owned by Chinese giant ByteDance.

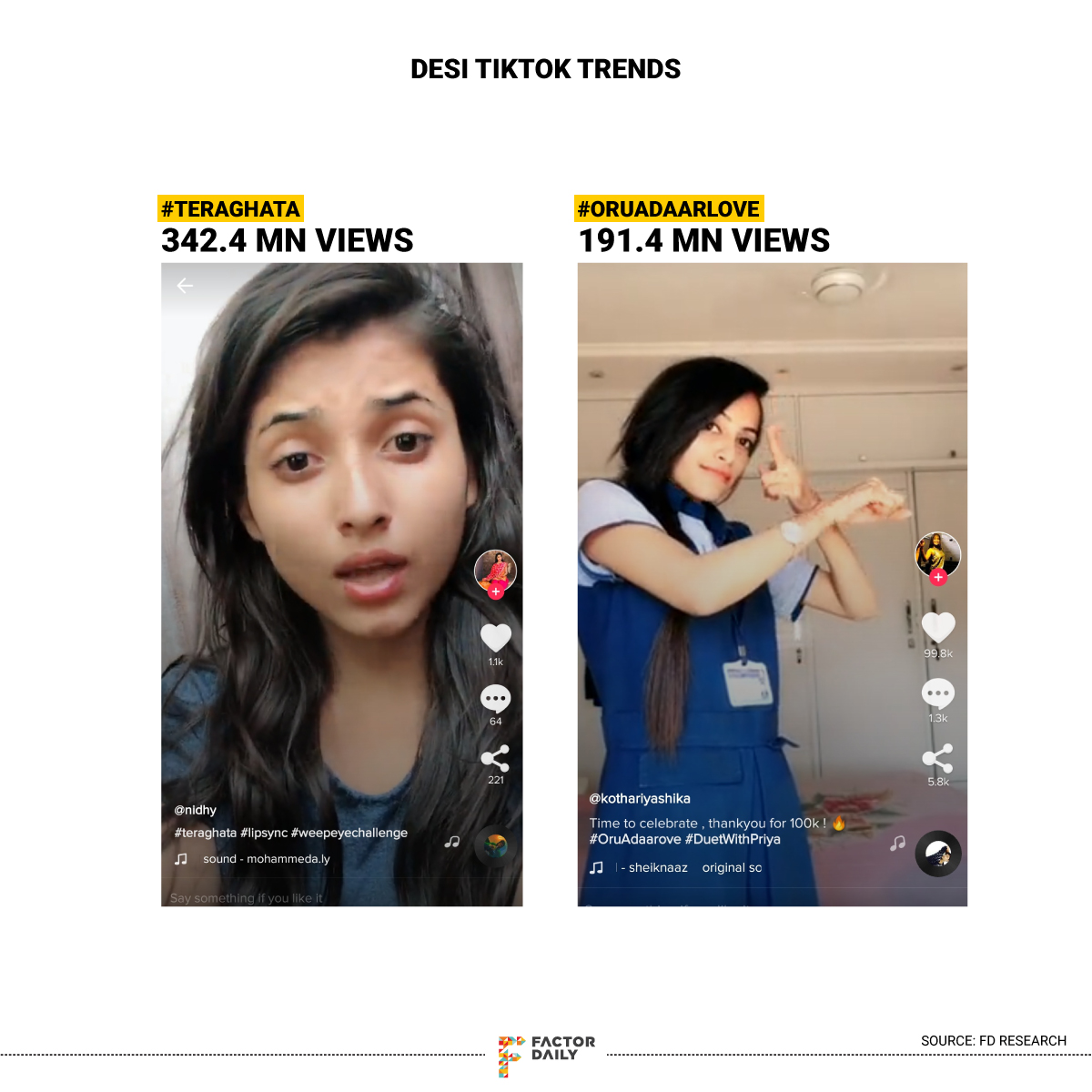

For instance, its local content around Diwali got 2.3 billion views on TikTok platform. Challenges around desi content like a popular Hindi song Tera Ghata gets a 342.4 million views — comparable to the top 25 all-time views on YouTube India. A meme of a Malayalam movie Oru Adaar Love gets 191.4 million views. The company has a local content team in Mumbai whose job is to find relevant trends and make challenges and memes out of them.

TikTok creator Shivani Kapila who has some 600,000 fans says the fact that the platform allows you to create content as short as a 15-second video makes it much easier to keep up. A bunch of tools, pre-fed memes, and challenges, too, help.

“The content on TikTok is much more relatable to people with varied interest. Also, as a creator you don’t always need to worry about what your next piece of video should be,” says Kapila.

A list of popular creators on TikTok sent by the company includes a handful of artistes who backflip, do mimicry, or are gymnasts. A majority of these creators are not what could be categorised for a certain talent. Some of them lipsync popular Tamil movie dialogues. Some have whacky content like a shirtless young man lying in the bed and talking about how to get rid of pimples (this user has 1.2 million fans).

“A large part of our localisation effort is directed towards creating culturally relevant content and formats,” a TikTok spokesperson tells FactorDaily.

TikTok’s emphasis through its filters and stickers is to have interactive visual elements that are relevant and funny. “But we focus on keeping it real. The focus is not necessarily on making you look cute,” the spokesperson emphasises.

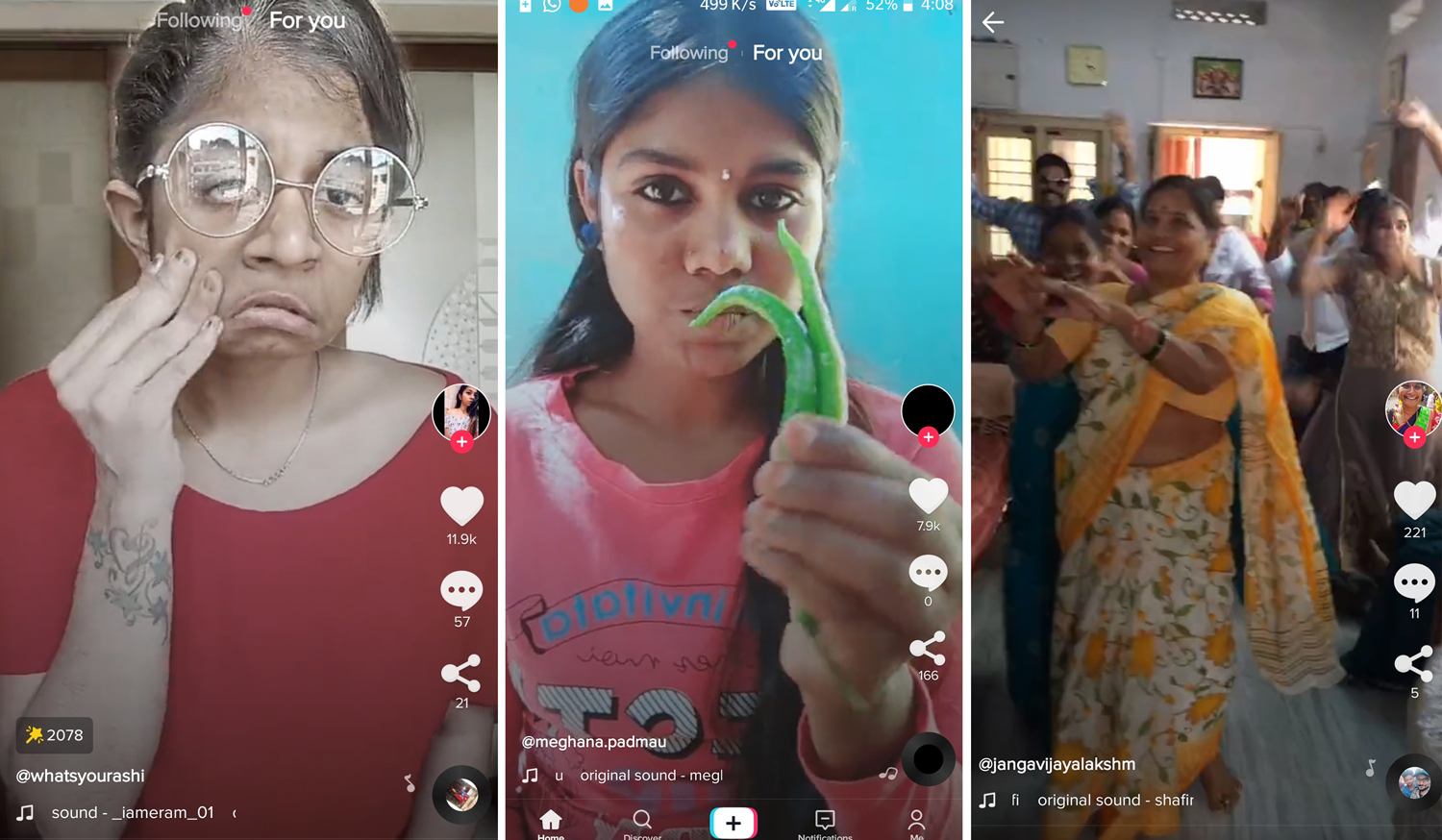

If you look at the popular content on the platform, it is not politically correct and is actually the opposite of conventionally cute. Videos of weeping boys, a crying middle aged woman begging for food, transformation of girls from conventionally ugly to conventionally beautiful (girls put on makeup to look darker or older for this video) or a fat man hiding a currency note within the layers of his tummy are hits on TikTok.

The fondness of Indian consumers towards humour that leans away from empathy and towards being crass is well known. TV shows like The Kapil Sharma Show that rely heavily on humour based on physical appearance of people – fat men dressed as women or referring to dark-skinned people as Africans – have enjoyed phenomenal popularity in the past. As consumers of cringeworthy content, we have celebrated creators like Dhinchak Pooja and Taher Shah in the past.

Kakkar, the TikTok creator who deals with body image issues, makes an interesting point. He says his sister urged him to make dance videos because she thought he would be more popular than her on TikTok. This is in stark contrast to the popular social media belief that accounts of women are more popular than that of men. Kakkar says his popularity is a function of both his dancing talent and the fact that it’s a fat man dancing.

“Among other messages I get on the platform, including negative ones around my body weight, there are also messages from other overweight people who aspire to be able to dance like that and put their videos out there,” he says.

Largely targeted at teenagers and young people, TikTok in India has 78% users under 25. Apart from English and Hindi, it has been seeing traction in regional language content including Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Marathi, and Punjabi.

In many ways, videos raging on TikTok – from a young man milking a cow to construction workers using wooden beams as violin to background music, from women dancing in a cowshed to a teenage-plus youngster walking crying out of his girlfriend’s wedding to an old man bathing under a hand pump – show a side of rural India that hasn’t been explored on other social media platforms as much.

TikTok has penetrated in almost 10% of India’s internet user base. While it still lags behind the penetration that Google, Facebook and Instagram enjoy in the country, it is slowly climbing up the ranks through content that is relatable, realistic and genuine.

Independent journalist Saurabh Sharma, who has reported from upcountry Uttar Pradesh and other parts of north India, pins TikTok’s following to humour that tickles the average Ashok Kumar in an Indian village, even though it may be lacking in empathy. “You and I won’t have an active TikTok account because we wouldn’t know what to post there,” Sharma tells me. But in small towns or villages, a short 15-second video of a boy falling from a cycle counts as entertainment. “In backward districts like Behrai, Facebook is a platform for intellectuals,” he says. “People don’t use their phones to know what (Prime Minister Narendra) Modi said, they want to have a good laugh.”

And, this holds true across almost all of smalltown India, Sharma posits. Perhaps. But, the platform hasn’t been able to shake off its reputation of promoting crass and cringey content. “TikTok is where people post stupid content,” says Mehak Agarwal, a 23 year old student pursuing her masters in technology at Indira Gandhi Delhi Technical University for Women, emphatically.

There are threads on web content rating platform Reddit discussing why does TikTok gets an unreasonable amount of hate among internet users. In the past, the platform has run into trouble for its misuse and lack of privacy in other countries.

To shed off its reputation, TikTok recently partnered with Cyber Peace Foundation, a non-profit that promotes cyber safety. It also launched a safety quiz on its app, that asks users basic safety questions like what kind of personal details are alright to reveal in a video or what objects are appropriate to be highlighted in a video. The effort is a work in progress, clearly.

Some observers of media and its users around the world have described TikTok as a breath of fresh air among the prevailing toxicity on other social media platforms. Much of it is powered by artificial intelligence under the ByteDance hood. On powering up the app, the TikTok platform lands a new (or even an existing) user directly on a “For you” page where users can start swiping down to view the list of short videos that are algorithmically presented.

As Rob Horning, editor for Real Life Magazine points in his newsletter “ByteDance is not interested in who you think you are or what you think you want: It instead intends to remake you in the image of what it can deliver.” Horning adds that with TikTok there is no pretense that users have conscious, considered wants that the platform can hear and respond to; it instead presents itself as an assiduous butler who anticipates what one needs and presents it before one thought to ask. “Because once people are used to being bottle-fed, they might not think to ask for anything other than formula.”

Be that as it may, TikTok today has insights on Indian users that it wants to hawk. It has started experimenting with ads in the US and also in India. According to a marketing deck by TikTok in India, the platform is pitching to advertisers based on its varied content and algorithmic prowess. Based on platform behaviour, TikTok tags user traits such as student, couple, goddess, aged 23, DSLR etc. along with environment data points like temple, desert, iPhone X, holiday, and Wi-Fi, as also content points funny, pet, dance, gourmet etc. Such traits can be useful for ad targeting as the platform looks to monetise in India market.

Among other usual ad formats that the platform is offering to brands in India, the pitch deck also suggests advertisements in the form of hashtag challenges, a popular meme format on the platform. The company promises brands positive comments and branded user-generated content, among other metrics. The company says it is only experimenting with ads in India and is not thinking of monetisation in this market right away. Native ads from brands like Shaadi.com and Myntra are already live on the platform.

Will TikTok be able to sustain its approach to content as it monetises the platform – e.g.: strategically placing a cosmetic brand ad to an acne prone boy or to promoting a denim challenge to a fashionista? Its raw, in your face, sans filters content strategy got it so far. The results of its early monetisation efforts will decide where the latest Chinese sensation in town goes from here.